The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

A direct Emilian influence on the development of scagliola in northern Italy came from the Leoni brothers, Ludovico, Giovanni and Francesco. Natives of Carpi, they had trained under Annibale Griffoni. Early in their careers their father, Battista (1614-1698), also a scagliolist, was found guilty of murder, stripped of his possessions and sentenced to death. He fled the Duchy of Modena and settled in Cremona in Lombardy, taking his sons with him. Giovanni, the middle brother, was the most accomplished scagliolist. The oldest, Ludovico (see below) was active in Cremona, where he had a prolific output. Little is known of Francesco (b. 1641) other than that he left four scagliola altar fronts in Grangia di Leri, in the province of Vercelli, Piedmont, one of which was signed but has been stolen in modern times. (A photograph was taken before the theft).

Ludovico Leoni (Carpi 1637- Cremona 1727)

Before moving to Lombardy, Ludovico had made altar fronts for the church of St. Augustine in Modena (subsequently destroyed in the Napoleonic occupation) and his parents’ family chapel in Carpi (also lost). Having settled in Cremona, he remained there for the rest of a long and active life, producing altar pieces and tabletops.

His earliest attributed work (1661) is a paliotto in the Theatine church of Santa Cristina in Parma, which features a central wooden cross surrounded by a rich and colourful display of flowers and foliage. The attribution is made in an article by Micaela Mander, who sees the Leoni family as the principle conduit for the introduction of scagliola to Lombardy (see references below).

An altar piece attributed to Ludovico Leoni in 1661, in the Church of Santa Cristina, Parma.

Later works by Ludovico have an outer border formed from geometrically shaped tiles of imitation marble, a distinctive feature that also appears in Giovanni’s later work.* Several altar pieces in this style have been attributed to Ludovico in the churches of Fidenza, Salsomaggiore and Busseto, as well as Cremona itself.

Altar front in the church of Christo Salvatore in Salsominore (Parma) signed with the name of the donor – R. Paulo Pisseud – and dated 1686. Manni attributes it to Ludovico Leoni on grounds of similarity and proximity to other confirmed work.

* Whether this type of border was the brothers’ own innovation or something they encountered locally and copied is unknown; the use of decorative imitation marble tiles and gemstones recalls the work of Blasius and Wilhelm Fistulator, but more importantly, of inlaid marble work in general. It was popular in Ancient Roman times, where it served a decorative purpose; and in the Christian era, when it relates symbolically to the arrangement of the precious stones that went to make up the Temple of the New Jerusalem, as described in the Apocalypse of St. John.

Ludovico Leoni is also credited with a distinctive series of eight early eighteenth century altar fronts.** Tripartite in design, they feature geometrically shaped panels of different shapes and sizes which contain images of religious figures expressed in an off-white imitation ivory colour, with line drawing and some cross-hatched shading in black. The quality of the shading is not as sophisticated as that of Carpi, and the reliance on line drawing, also used in places to depict swirling ‘ivoried’ foliage, gives these paliotti a less refined appearance than their Emilian counterparts. There are several of these works in the church of San Sepolcro in Piacenza, and a smaller one, (possibly the central panel of a larger work), in Parma Cathedral.

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza, showing Santa Barbara in the cetral panel, flanked by two flower vases and angels. (Att. Ludovico Leoni and dated 1716.)

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza. The central panel depicts the Madonna and St. John beside the Crucified Christ. (Att. Ludovico Leoni.)

An altar front in Parma Cathedral which bears an obvious resemblance to those in Piacenza.

** None of these works are signed or documented, but Ludovico Leoni’s authorship has been asserted on the basis of anecdote and stylistic similarities. For a full catalogue of Ludovico Leoni’s work in the Cremona region see G. Manni’s I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romana e Marche.

Giovanni Leoni (1639 – early 1700s)

Giovanni Leoni was one of the foremost Carpi-trained scagliolists and his surviving works are of very high quality. They include, in adition to some impressive altar fronts, several table tops and an outstanding pair of decorative cabinets he made for the royal court of Modena. Overall he appears to have been more involved in secular than religious works, making him unusual for the area. (Many of these works are in private hands; high quality photographs can be found in G. Manni’s I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romana e Marche.)

Like his brother Ludovico, he too worked away from Emilia for most of his life, setting up workshops in Milan and Genoa before eventually moving back to Modena. In 1661, aged twenty one, he signed and dated his earliest surviving work, a tabletop similar in design to the one made by his brother Ludovico in the same decade. In the central panel a parrot perches on a branch, framed by an octagonal border filled with marble tiles. Surrounding this is a symmetrical arrangement of foliage and flowers, and around the edge a border made up of larger marble tiles. The design is elegant and the depiction of the parrot and the flowers naturalistic; an unusual feature is the brightness and strength of the colours, which are unusually bright when compared with the subtle shades favoured by the Carpi producers of the period.¹

A further work, a small coloured panel (47cms. x 34cms) signed and dated 1668, depicts the Sacred Family and Trinity against a black background; modelling and depth are achieved through a combination of colour and crosshatching. Where the tabletop of 1661 imitates Pietre Dure inlay, this panel is a scagliola painting. The date is well in advance of the scagliola paintings of Pozzuoli and Massa, and shows considerable control and confidence. It is clear that Giovanni Leoni was keen to try new things, and contemporaries considered his work to be distinguished from that of his predecessors and peers by its originality and strangeness (una curiosa bizzarria di ispirazione).²

In 1680-1681 Giovanni produced a pair of decorative cabinets with inlaid scagliola panels, made for Prince Ignazio d’Este of Modena. At the time he was living in Milan, from where he sent a letter requesting payment, and describing himself as a maker of furniture (fabricante di scrittori). The two cabinets, signed and dated, are extremely fine and considered his masterpieces. Each one is faced with over twenty scagliola panels of varying shapes and sizes, set in moulded black scagliola frames; they depict conventional Pietre Dure motifs of the day, birds on branches, floral arrangements and marble tiles. A central mirrored cavity is flanked by two inversely tapering pilasters and two salomonic columns, which stand on a scagliola platform inlaid with playing cards. The cabinets are decorated with gilt bronze mountings, and sit on carved timber supports, gessoed to look like ebony.

The design of each panel is finely balanced, and the detailing and naturalism of the birds and flowers is exceptional. The two cabinets are similar in construction and appearance to the Pietre Dure cabinets produced by the Florentine Galleria dei Lavori in the seventeenth century. They are one of the most significant secular commissions of scagliola for the period, and demonstrate the prestige that northern Italian scagliola had achieved by the 1680s. 3

1683 Giovanni Leoni signed an altar front for the church of San Vittore al Corpo in Milan. In this piece naturalistic foliage and flowers develop from stylised banding which surrounds a central image of an empty Cross; the border is again formed from imitation marble tiles, though in this case the shapes are more varied and interesting. Strong yellows and oranges predominate, balanced by the subtle browns, pinks and greens of the flowers and foliage.

A tabletop signed and dated in Genoa in 1685 (Gio. Leone F. in Genova 1685), now held in the Rijksmueum, Amsterdam, is the last confirmed work of this scagliolist. It was made for the renowned ambassador and scholar Nicolaas Witsen (1641-1717), who was mayor of Amsterdam at the time; his coat of arms, supported by thick acanthus leaves, is in the centre of the table, surrounded by four separate images of birds on flowering branches and two shallow baskets of fruit and flowers. The outer border, set between plain white bands, is filled with a richly portrayed frieze of flowers and fruit, similar in design and colouring to the contemporary work of Barzelli (see Chapter 19). The decorative work, on a black background, is colourful and naturalistic. Once again the table is an impressive example of inlaid scagliola in the style of contemporary Pietre Dure.

Giovanni Leoni’s last known work, an inlaid scagliola tabletop made for the Dutch ambassador and scholar Nicolaas Witsen. (Signed and dated 1685 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Click on small images to expand).

The presence in Milan and then Genoa of such a skilled scagliolist with important secular clients both north and south of the Alps encouraged the spread of scagliola throughout the region. Manni sees the influence of Giovanni Leoni in the work of Lorenzo Bonucelli, another scagliolist who was active at the royal court of Turin from the 1680s to the early 1700s (see chapter…). Neumann connected the development of scagliola production in Lucca and Livorno in the early eighteenth century with Leoni’s presence in Genoa.

1. G. Manni Ibid… p. 138-139. The photograph Manni publishes of the tabletop shows it shortly after restoration. Whether the restoration process (or the photo) has returned the colours to their original appearance is impossible to say.

2. A photograph of the panel is published in G. Manni ibid. p 138-139. The Italian comment is quoted from Erwin Neuman’s article p. 152.

3. In 1870, following the unification of Italy, the cabinets – valued at 20.000 lire – were sent to Vienna as part of an agreement between the commune of Modena and the deposed duke, Francesco V; in return, the commune retained the marble bust of Francesco I by Bernini, which it acknowledged to have been the personal property of the d’Este family. The cabinets subsequently disappeared from view and were considered lost. They were rediscovered by Graziano Manni at the end of the last century in the castle of Konopiste in Czeckoslovakia, in remarkably good condition. Manni provides a full decription of the history of these cabinets along with several photographs. See Manni pp 140-145.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152

Micaela Mander: Scagliola tra Emilia e Lombardia: una sintesi, in ‘Scagliola intarsiate, Arte e tecnica nel territorio ticinese tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo’, a cura di Elfi Rüsch. Silvana Editoriale, Milano 2007.

The Comasques and the Intelvi Valley.

Since the Middle Ages the area around Como and the Italian lakes had produced families of itinerant builders and masons, forced by the poverty of their mountainous homeland to seek work elsewhere. They found it to the south in the major Italian cities, to the east in the Austrian hereditary crown lands, and to the north in Germany and the Holy Roman Empire. During the sixteenth century they added decorative stucco and fresco work to their repertory of building skills, thereby increasing the range of their activities in both religious and secular building; it was only a matter of time before they encountered and assimilated scagliola. The Intelvi valley, which runs between Lake Como and Lake Lugano, became an important centre of religious scagliola production from the second half of the seventeenth century until the end of the eighteenth.*

* In her classification of Intelvi altar pieces, Floriana Spalla Gandola gives 1580-1650 as the approximate dates for the earliest type of paliotto. This seems early for the region, implying that Intelvi scagliola production pre-dated even that of Bavaria; to my knowledge, no other modern writers on scagliola have made this claim and I am unaware of any reliably dated pieces. See Floriana Spalla Scagliola Intelvese, Formazione e Belleza p. 26 (in Imitazione e Belleza) Ghiffa 2004.

Don Carlo Belleni (Val d’Intelvi 1612-1683)

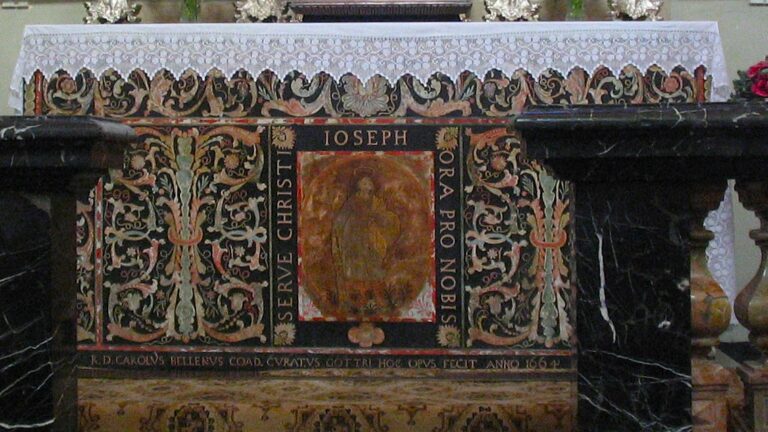

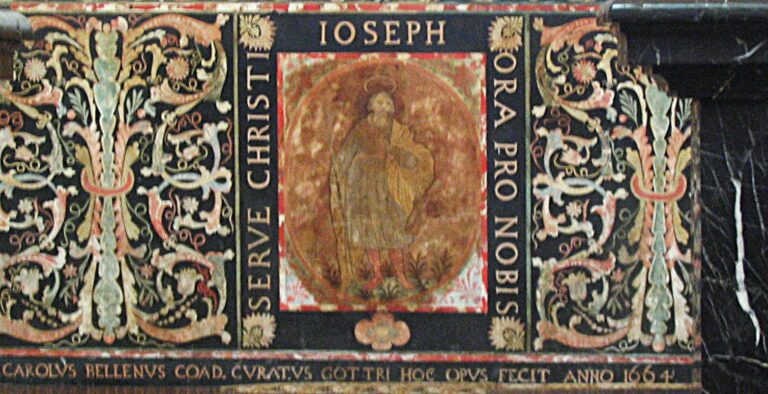

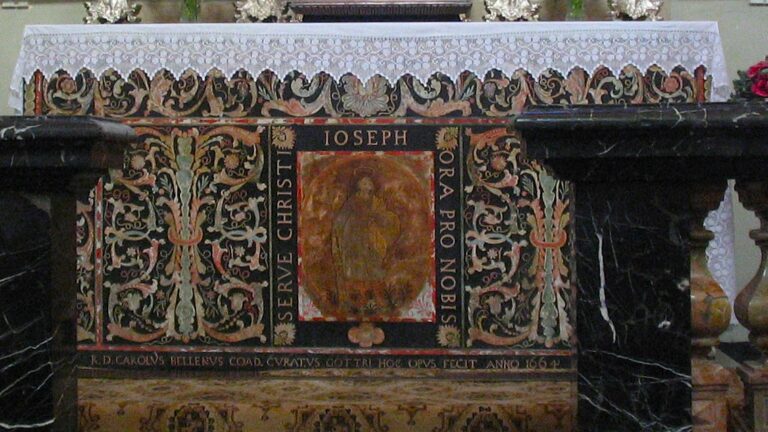

One of the earliest scagliola altar pieces in the Lombardy region, signed and dated by its maker (Don Carlo Belleni – 1664), can be found in a side chapel in the parish church of San Stefano in the Intelvi village of Gottro, where Don Carlo was the parish priest.¹

The central panel of the tripartite altar front has a picture (badly stained) of St. Joseph, set in a black frame with an inlaid dedication; the side panels and frieze are filled with stylised arrangements of scrolling foliage and flowers. The design and execution is unlike any contemporary altar pieces from Carpi, pre-dating the Carpigian use of full colour on a black background by several years.²

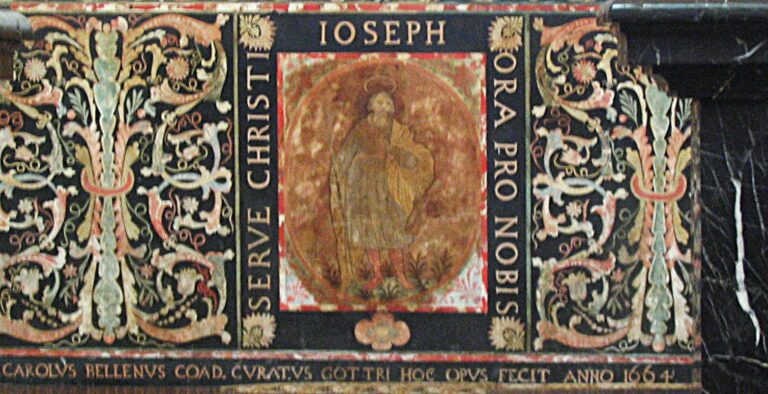

An early scagliola altar piece in the Parish Church of San Stefano in Gottro, Carlazzo, nr. Como. It was made by the Parish Priest, Don Carlo Belleni, and signed and dated 1664 (see close-up below).

Close-up of the above work showing the maker’s name and the date.

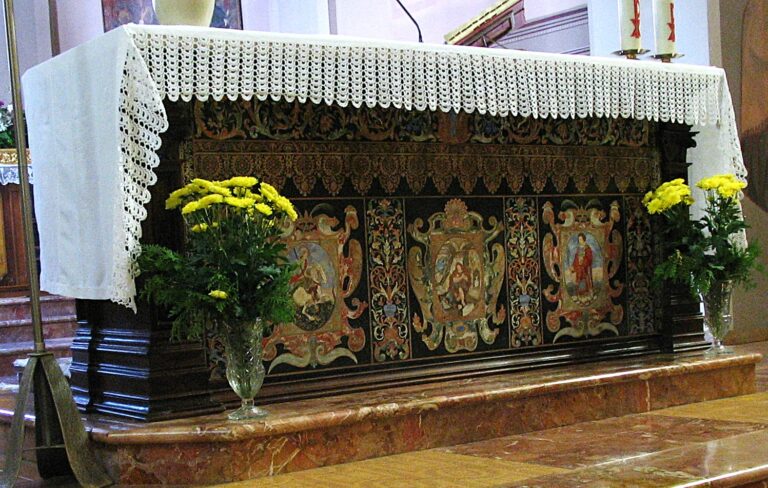

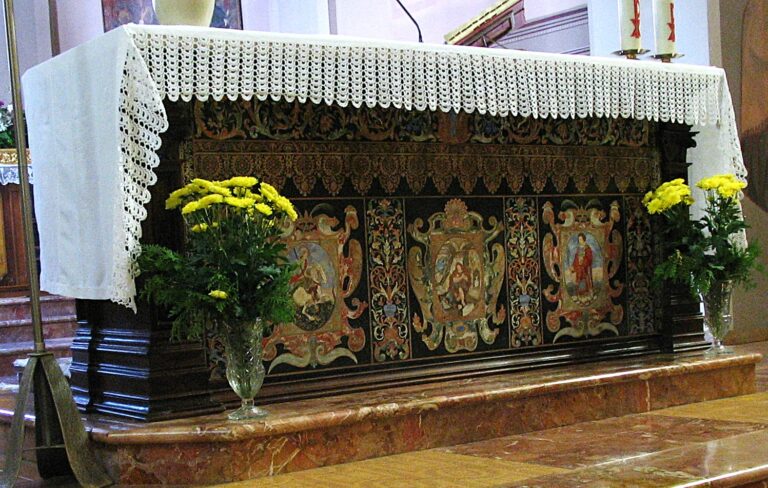

The main altar front of the church, undated, consists of three panels separated by four candelabra, with a band of lacework and scrolling foliage above, and a thin strip of lacework around the edge. The panels contain baroque cartouches with pictures of St. George, St. Mary Magdalene and St. Stephen. The form of the design is close to Gavignani’s, but once again the inlays are in colour.

The main altar in the Parish Church of San Stefano, Gottro. Although unsigned, it is sylistically very close to the previous work and almost certainly by the same hand.

Details of the pictorial panels showing St. George, St. Mary Magdalene and St. Stephen.

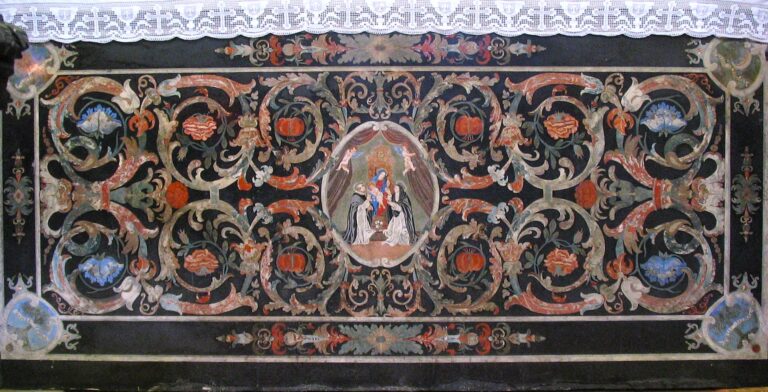

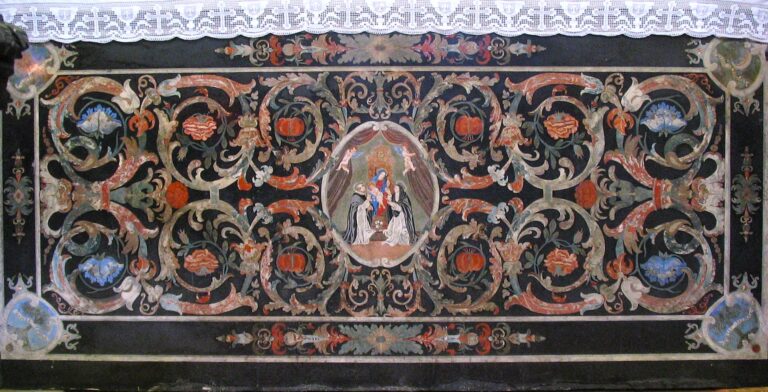

A second side altar has a single central field filled with scrolling foliage and flowers surrounding an oval frame with a picture of the Enthroned Virgin and Child with two Saints. Stylised floral arrangements and corner cartouches with symbolic images are contained within a plain outer border. The unified design is unlike the previous two ‘tri-partite’ pieces, but the colours are very similar. The paliotto is not signed or dated, but could well be considered a third, possibly later, example of Don Carlo Beleni’s work.

Side altar scagliola paliotto in the Church of San Stefano, Gottro, probably also by Don Carlo Belleni (third quarter 17th. C.)

Behind the altar, a curved bank of choir stalls is attached to the wall of the apse. Let into their backs are black scagliola panels, with alternating coloured images of religious figures and vases of flowers; beneath them, there are smaller panels with geometrical inlays, the central one dated 1667. Two further panels, depicting St. George and St. Victor, are attached to the underside of the arch of one of the side chapels.

Inlaid scagliola panels in the backs of the the choir stalls of San Stefano, Gottro (attr. Don Belleni, dated 1667).

Italian writers have made much of Don Belleni’s use of scagliola in the choir stalls of San Stefano, finding evidence of a link with the German scagliola work in St. Lawrence, Kempten (see Chapter 13).³ The style is quite different however, and the German choir stall panels were made and installed between 1669 and 1670, two years after those of Gottro.* Furthermore, the decoration of choir stall backs was by no means a new concept; the use of elaborate marquetry inlays for this purpose was already well established throughout northern Italy.

How Don Belleni learnt the technique of inlaid scagliola is unknown. The Leoni family (see above) would be an obvious influence, and the mobility of the Lombard masons and stuccatori make it more than likely that information from both Emilia and Bavaria was circulating by the mid-1600s. At the same time the presence of the Corbarelli family had introduced Florentine Pietre Dure work to the churches of northern Italy, providing both models and a stimulus for scagliola development.

Scagliola work in this area of Italy never went beyond the imitation of Pietre Dure mosaic; this contrasts with Carpi, where the return to colour in the 1670s and 1680s saw a move towards a more naturalistic interpretation of decorative and pictorial subjects, culminating in the scagliola paintings of Pozzuoli and Massa.

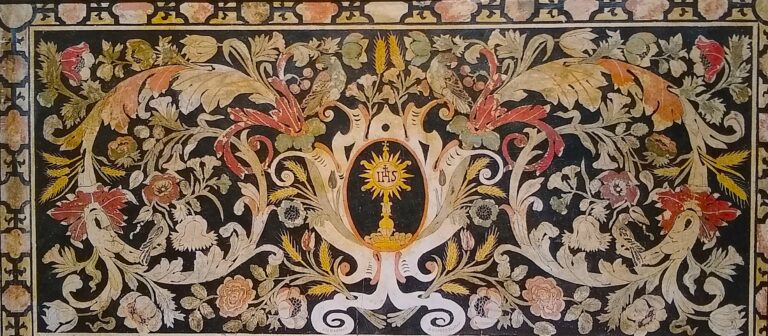

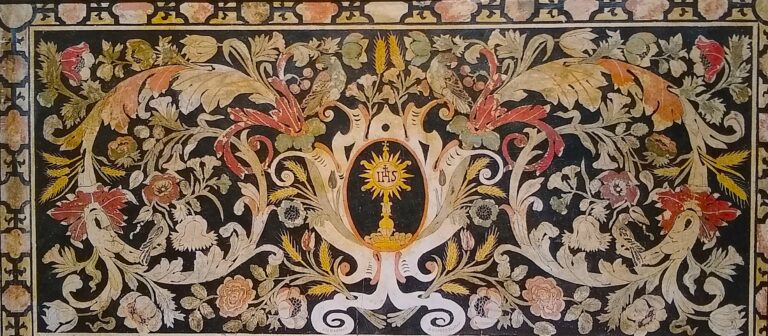

There is only one example in the Intelvi valley of the black and white technique so popular in Emilia Romagna. This is in the Oratorio of the Virgin of the Carmelites in Casasco d’Intelvi. The paliotto is made in three separate panels; the central panel has an image of the Jesuit sun and monogram, and the two sides have antique flower vases flanked by paired birds. The images are surrounded by wide borders containing black and white grotesques in the style of Giovanni Gavignani, with cross hatching and intricate detailing. The quality of this altar piece is exceptional, and the uniqueness of the decoration for this region implies the influence or authorship of a Carpi-trained scagliolist, perhaps Giovanni Leoni, perhaps, given the black and white technique, someone earlier.

A remarkable scagliola paliotto in the Oratorio of the Virgin of the Carmelites in Casasco d’Intelvi, in the Intelvi valley. The maker and the date are unknown.

1. A slightly earlier unsigned altar front can be seen in the lazaret (quarantine ward) of the Oratory of San Rocco in Osteno, bearing an inscription and the date 1659, which celebrates the end of a plague. Spalla proposes Andrea Solari, [father/brother of Francesco], as the author – See CD – La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi, curated by Floriana Spalla and Ernesto Palmieri produced by La Comunità Montana Lario Intelvese with Appacuvi. Itinerary 2.

2. Giovanni Gavignani’s black and white technique was the predominant means of expression for religious scagliola in Carpi during the 1650s and 60s; the full use of colour did not reappear there until the 1670s and 80s, with the work of Barzelli and Mazelli (see above Chapter 19). (One exception is the strongly coloured altar front in the parish church of San Geminiano in Guiglia, signed and dated 1666 by Simone Setti. a pupil of Gavignani. Setti moved to Modena and is credited by Cabassi with introducing scagliola to the city; he specialised in the production of tabletops for secular clients, normally using his master’s black and white technique to depict classical (as opposed to religious) themes and allegories).

3. See Garuti pp.92-95, also Manni p.23 and Massinelli p.

* Michaela Liebhardt Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts p. 159

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Floriana Spalla Gandola Scagliola Intelvesi, formazione e simbologia (in Imitazione e Belleza) Ghiffa 2004, also See CD – La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi, curated by Floriana Spalla and Ernesto Palmieri produced by La Comunità Montana Lario Intelvese with Appacuvi. Itinerary 2.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152

* Michaela Liebhardt Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts.

The Solari Family

The Solari family, from the small town of Verna high above Lake Lugano, produced three generations of scagliolists who worked in different parts of the region: Lombardy and Piedmont to the south and south west, Brescia to the south east, and Ticino and the Graubünden to the north. The family had already achieved fame in the person of Santino Solari (1576-1646), the court architect to Marcus Sitticus, Prince Bishop of Salzburg (r. 1612-1619), for whom he designed Schloss Hellbrun, a summer Pleasure Palace (Lustschloss) famously equipped with several grottos and waterworks.

Grottos had become popular in the second half of the sixteenth century, and their walls were often lined with coloured plaster imitating volcanic tufa and different rocks, into which shells, crystals, coral, and even gemstones were embedded. Observing the different effects that could be produced with coloured plaster was certainly one step along the road to discovering scagliola. Luciana Spalla suggests that Santino Solari’s experiences at Schloss Hellbrun may have provided the basis for his family’s subsequent discovery and mastery of the technique.*

Santino Solari went on to build the Cathedral in Salzburg, the first major baroque church north of the Alps.

* See Spalla in Imitazione e Belleza …p.23. Dorothea Diemer also thinks that grotto work may have contributed to the discovery of scagliola on the same grounds – that it involved experimentation with coloured plaster and the different effects that could be obtained with it. Blasius Fistulator is recorded as having worked on the statue of Mercury in the Munich Grottenhoff (grotto courtyard) in the 1580s. (See above Chapter 10.)

[ii]For this and all biographical details of the Solari family and other Intelvi scagliolists see Don Battista Cetti: Vita e Opera dei Maestri Comacini Milan 1993 (private publication) pp 158-175. Francesco’s status as founding father of the family’s scagliola activities is not accepted by Spalla, who attributes work to Pietro Solari senior (c.1630) and Francesco’s father or brother Andrea Solari (1659) See La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi... Itinerary 2.

Francesco Solari (1632-1703) was the family’s first scagliolist.[ii]

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Don Battista Cetti: Vita e Opera dei Maestri Comacini Milan 1993 (private publication) pp 158-175. Francesco’s status as founding father of the family’s scagliola activities is not accepted by Spalla (see below), who attributes work to Pietro Solari senior (c.1630) and Francesco’s father or brother Andrea Solari (1659)

La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi... Itinerary 2.Floriana Spalla Gandola Scagliola Intelvesi, formazione e simbologia (in Imitazione e Belleza) Ghiffa 2004, also See CD – La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi, curated by Floriana Spalla and Ernesto Palmieri produced by La Comunità Montana Lario Intelvese with Appacuvi. Itinerary 2.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152

* Michaela Liebhardt Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts.

A direct Emilian influence on the development of scagliola in northern Italy came from the Leoni brothers, Ludovico, Giovanni and Francesco. Natives of Carpi, they had trained under Annibale Griffoni. Early in their careers their father, Battista (1614-1698), also a scagliolist, was found guilty of murder, stripped of his possessions and sentenced to death. He fled the Duchy of Modena and settled in Cremona in Lombardy, taking his sons with him. Giovanni, the middle brother, was the most accomplished scagliolist. The oldest, Ludovico (see below) was active in Cremona, where he had a prolific output. Little is known of Francesco (b. 1641) other than that he left four scagliola altar fronts in Grangia di Leri, in the province of Vercelli, Piedmont, one of which was signed but has been stolen in modern times. (A photograph was taken before the theft).

Ludovico Leoni (Carpi 1637- Cremona 1727)

Before moving to Lombardy, Ludovico had made altar fronts for the church of St. Augustine in Modena (subsequently destroyed in the Napoleonic occupation) and his parents’ family chapel in Carpi (also lost). Having settled in Cremona, he remained there for the rest of a long and active life, producing altar pieces and tabletops.

His earliest attributed work (1661) is a paliotto in the Theatine church of Santa Cristina in Parma, which features a central wooden cross surrounded by a rich and colourful display of flowers and foliage. The attribution is made in an article by Micaela Mander, who sees the Leoni family as the principle conduit for the introduction of scagliola to Lombardy (see references below).

An altar piece attributed to Ludovico Leoni in 1661, in the Church of Santa Cristina, Parma.

Later works by Ludovico have an outer border formed from geometrically shaped tiles of imitation marble, a distinctive feature that also appears in Giovanni’s later work.* Several altar pieces in this style have been attributed to Ludovico in the churches of Fidenza, Salsomaggiore and Busseto, as well as Cremona itself.

Altar front in the church of Christo Salvatore in Salsominore (Parma) signed with the name of the donor – R. Paulo Pisseud – and dated 1686. Manni attributes it to Ludovico Leoni on grounds of similarity and proximity to other confirmed work.

* Whether this type of border was the brothers’ own innovation or something they encountered locally and copied is unknown; the use of decorative imitation marble tiles and gemstones recalls the work of Blasius and Wilhelm Fistulator, but more importantly, of inlaid marble work in general. It was popular in Ancient Roman times, where it served a decorative purpose; and in the Christian era, when it relates symbolically to the arrangement of the precious stones that went to make up the Temple of the New Jerusalem, as described in the Apocalypse of St. John.

Ludovico Leoni is also credited with a distinctive series of eight early eighteenth century altar fronts.** Tripartite in design, they feature geometrically shaped panels of different shapes and sizes which contain images of religious figures expressed in an off-white imitation ivory colour, with line drawing and some cross-hatched shading in black. The quality of the shading is not as sophisticated as that of Carpi, and the reliance on line drawing, also used in places to depict swirling ‘ivoried’ foliage, gives these paliotti a less refined appearance than their Emilian counterparts. There are several of these works in the church of San Sepolcro in Piacenza, and a smaller one, (possibly the central panel of a larger work), in Parma Cathedral.

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza, showing Santa Barbara in the cetral panel, flanked by two flower vases and angels. (Att. Ludovico Leoni and dated 1716.)

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza. The central panel depicts the Madonna and St. John beside the Crucified Christ. (Att. Ludovico Leoni.)

** None of these works are signed or documented, but Ludovico Leoni’s authorship has been asserted on the basis of anecdote and stylistic similarities. For a full catalogue of Ludovico Leoni’s work in the Cremona region see G. Manni’s I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romana e Marche.

Giovanni Leoni (1639 – early 1700s)

Giovanni Leoni was one of the foremost Carpi-trained scagliolists and his surviving works are of very high quality. They include, in adition to some impressive altar fronts, several table tops and an outstanding pair of decorative cabinets he made for the royal court of Modena. Overall he appears to have been more involved in secular than religious works, making him unusual for the area. (Many of these works are in private hands; high quality photographs can be found in G. Manni’s I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romana e Marche.)

Like his brother Ludovico, he too worked away from Emilia for most of his life, setting up workshops in Milan and Genoa before eventually moving back to Modena. In 1661, aged twenty one, he signed and dated his earliest surviving work, a tabletop similar in design to the one made by his brother Ludovico in the same decade. In the central panel a parrot perches on a branch, framed by an octagonal border filled with marble tiles. Surrounding this is a symmetrical arrangement of foliage and flowers, and around the edge a border made up of larger marble tiles. The design is elegant and the depiction of the parrot and the flowers naturalistic; an unusual feature is the brightness and strength of the colours, which are unusually bright when compared with the subtle shades favoured by the Carpi producers of the period.

A further work, a small coloured panel (47cms. x 34cms) signed and dated 1668, depicts the Sacred Family and Trinity against a black background; modelling and depth are achieved through a combination of colour and crosshatching. Where the tabletop of 1661 imitates Pietre Dure inlay, this panel is a scagliola painting. The date is well in advance of the scagliola paintings of Pozzuoli and Massa, and shows considerable control and confidence. It is clear that Giovanni Leoni was keen to try new things, and contemporaries considered his work to be distinguished from that of his predecessors and peers by its originality and strangeness (una curiosa bizzarria di ispirazione).²

In 1680-1681 Giovanni produced a pair of decorative cabinets with inlaid scagliola panels, made for Prince Ignazio d’Este of Modena. At the time he was living in Milan, from where he sent a letter requesting payment, and describing himself as a maker of furniture (fabricante di scrittori). The two cabinets, signed and dated, are extremely fine and considered his masterpieces. Each one is faced with over twenty scagliola panels of varying shapes and sizes, set in moulded black scagliola frames; they depict conventional Pietre Dure motifs of the day, birds on branches, floral arrangements and marble tiles. A central mirrored cavity is flanked by two inversely tapering pilasters and two salomonic columns, which stand on a scagliola platform inlaid with playing cards. The cabinets are decorated with gilt bronze mountings, and sit on carved timber supports, gessoed to look like ebony.

The design of each panel is finely balanced, and the detailing and naturalism of the birds and flowers is exceptional. The two cabinets are similar in construction and appearance to the Pietre Dure cabinets produced by the Florentine Galleria dei Lavori in the seventeenth century. They are one of the most significant secular commissions of scagliola for the period, and demonstrate the prestige that northern Italian scagliola had achieved by the 1680s. ³

In 1683 Giovanni Leoni signed an altar front for the church of San Vittore al Corpo in Milan. In this piece naturalistic foliage and flowers develop from stylised banding which surrounds a central image of an empty Cross; the border is again formed from imitation marble tiles, though in this case the shapes are more varied and interesting. Strong yellows and oranges predominate, balanced by the subtle browns, pinks and greens of the flowers and foliage.

A tabletop signed and dated in Genoa in 1685 (Gio. Leone F. in Genova 1685), now held in the Rijksmueum, Amsterdam, is the last confirmed work of this scagliolist. It was made for the renowned ambassador and scholar Nicolaas Witsen (1641-1717), who was mayor of Amsterdam at the time; his coat of arms, supported by thick acanthus leaves, is in the centre of the table, surrounded by four separate images of birds on flowering branches and two shallow baskets of fruit and flowers. The outer border, set between plain white bands, is filled with a richly portrayed frieze of flowers and fruit, similar in design and colouring to the contemporary work of Barzelli (see Chapter 19). The decorative work, on a black background, is colourful and naturalistic. Once again the table is an impressive example of inlaid scagliola in the style of contemporary Pietre Dure.

Giovanni Leoni’s last known work, an inlaid scagliola tabletop made for the Dutch ambassador and scholar Nicolaas Witsen. (Signed and dated 1685 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Click on small images to expand).

The presence in Milan and then Genoa of such a skilled scagliolist with important secular clients both north and south of the Alps encouraged the spread of scagliola throughout the region. Manni sees the influence of Giovanni Leoni in the work of Lorenzo Bonucelli, another scagliolist who was active at the royal court of Turin from the 1680s to the early 1700s (see chapter…). Neumann connected the development of scagliola production in Lucca and Livorno in the early eighteenth century with Leoni’s presence in Genoa.

1. G. Manni Ibid… p. 138-139. The photograph Manni publishes of the tabletop shows it shortly after restoration. Whether the restoration process (or the photo) has returned the colours to their original appearance is impossible to say.

2. A photograph of the panel is published in G. Manni ibid. p 138-139. The Italian comment is quoted from Erwin Neuman’s article p. 152.

3. In 1870, following the unification of Italy, the cabinets – valued at 20.000 lire – were sent to Vienna as part of an agreement between the commune of Modena and the deposed duke, Francesco V; in return, the commune retained the marble bust of Francesco I by Bernini, which it acknowledged to have been the personal property of the d’Este family. The cabinets subsequently disappeared from view and were considered lost. They were rediscovered by Graziano Manni at the end of the last century in the castle of Konopiste in Czeckoslovakia, in remarkably good condition. Manni provides a full decription of the history of these cabinets along with several photographs. See Manni pp 140-145.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152

Micaela Mander: Scagliola tra Emilia e Lombardia: una sintesi, in ‘Scagliola intarsiate, Arte e tecnica nel territorio ticinese tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo’, a cura di Elfi Rüsch. Silvana Editoriale, Milano 2007.

The Comasques and the Intelvi Valley.

Since the Middle Ages the area around Como and the Italian lakes had produced families of itinerant builders and masons, forced by the poverty of their mountainous homeland to seek work elsewhere. They found it to the south in the major Italian cities, to the east in the Austrian hereditary crown lands, and to the north in Germany and the Holy Roman Empire. During the sixteenth century they added decorative stucco and fresco work to their repertory of building skills, thereby increasing the range of their activities in both religious and secular building; it was only a matter of time before they encountered and assimilated scagliola. The Intelvi valley, which runs between Lake Como and Lake Lugano, became an important centre of religious scagliola production from the second half of the seventeenth century until the end of the eighteenth.*

* In her classification of Intelvi altar pieces, Floriana Spalla Gandola gives 1580-1650 as the approximate dates for the earliest type of paliotto. This seems early for the region, implying that Intelvi scagliola production pre-dated even that of Bavaria; to my knowledge, no other modern writers on scagliola have made this claim and I am unaware of any reliably dated pieces. See Floriana Spalla Scagliola Intelvese, Formazione e Belleza p. 26 (in Imitazione e Belleza) Ghiffa 2004.

Don Carlo Belleni (Val d’Intelvi 1612-1683)

One of the earliest scagliola altar pieces in the Lombardy region, signed and dated by its maker (Don Carlo Belleni – 1664), can be found in a side chapel in the parish church of San Stefano in the Intelvi village of Gottro, where Don Carlo was the parish priest.¹

The central panel of the tripartite altar front has a picture (badly stained) of St. Joseph, set in a black frame with an inlaid dedication; the side panels and frieze are filled with stylised arrangements of scrolling foliage and flowers. The design and execution is unlike any contemporary altar pieces from Carpi, pre-dating the Carpigian use of full colour on a black background by several years.²

An early scagliola altar piece in the Parish Church of San Stefano in Gottro, Carlazzo, nr. Como. It was made by the Parish Priest, Don Carlo Belleni, and is signed and dated 1664 (see close-up below).

Close-up of the above work showing the maker’s name and the date.

The main altar front of the church, unsigned and undated, consists of three panels separated by four candelabra, with a band of lacework and scrolling foliage above, and a thin strip of lacework around the edge. The panels contain baroque cartouches with pictures of St. George, St. Mary Magdalene and St. Stephen. The form of the design is close to Gavignani’s, but once again the inlays are in colour

The main altar in the Parish Church of San Stefano, Gottro. Although unsigned, it is sylistically very close to the previous work and almost certainly by the same hand.

Details of the pictorial panels showing St. George, St. Mary Magdalene and St. Stephen.

A second side altar has a single central field filled with scrolling foliage and flowers surrounding an oval frame with a picture of the Enthroned Virgin and Child with two Saints. Stylised floral arrangements and corner cartouches with symbolic images are contained within a plain outer border. The unified design is unlike the previous two ‘tri-partite’ pieces, but the colours are very similar. The paliotto is not signed or dated, but could well be considered a third, possibly later, example of Don Carlo Beleni’s work.

Side altar scagliola paliotto in the Church of San Stefano, Gottro, probably also by Don Carlo Belleni (third quarter 17th. C.)

Behind the altar, a curved bank of choir stalls is attached to the wall of the apse. Let into their backs are black scagliola panels, with alternating coloured images of religious figures and vases of flowers; beneath them, there are smaller panels with geometrical inlays, the central one dated 1667. Two further panels, depicting St. George and St. Victor, are attached to the underside of the arch of one of the side chapels.

Inlaid scagliola panels in the backs of the the choir stalls of San Stefano, Gottro (attr. Don Belleni, dated 1667).

Italian writers have made much of Don Belleni’s use of scagliola in the choir stalls of San Stefano, finding evidence of a link with the German scagliola work in St. Lawrence, Kempten (see Chapter 13).³ The style is quite different however, and the German choir stall panels were made and installed between 1669 and 1670, two years after those of Gottro.* Firthermore, the decoration of choir stall backs was by no means a new concept; the use of elaborate marquetry inlays for this purpose was already well established throughout northern Italy.

How Don Belleni learnt the technique of inlaid scagliola is unknown. The Leoni family (see above) would be an obvious influence, and the mobility of the Lombard masons and stuccatori make it more than likely that information from both Emilia and Bavaria was circulating by the mid-1600s. At the same time the presence of the Corbarelli family had introduced Florentine Pietre Dure work to the churches of northern Italy, providing both models and a stimulus for scagliola development.

Scagliola work in this area of Italy never went beyond the imitation of Pietre Dure mosaic; this contrasts with Carpi, where the return to colour in the 1670s and 1680s saw a move towards a more naturalistic interpretation of decorative and pictorial subjects, culminating in the scagliola paintings of Pozzuoli and Massa.

There is only one example in the Intelvi valley of the black and white technique so popular in Emilia Romagna. This is in the Oratorio of the Virgin of the Carmelites in Casasco d’Intelvi. The paliotto is made in three separate panels; the central panel has an image of the Jesuit sun and monogram, and the two sides have antique flower vases flanked by paired birds. The images are surrounded by wide borders containing black and white grotesques in the style of Giovanni Gavignani, with cross hatching and intricate detailing. The quality of this altar piece is exceptional, and the uniqueness of the decoration for this region implies the influence or authorship of a Carpi-trained scagliolist, perhaps Giovanni Leoni, perhaps, given the black and white technique, someone earlier.

A remarkable scagliola paliotto in the Oratorio of the Virgin of the Carmelites in Casasco d’Intelvi, in the Intelvi valley. The maker and the date are unknown.

1. A slightly earlier unsigned altar front can be seen in the lazaret (quarantine ward) of the Oratory of San Rocco in Osteno, bearing an inscription and the date 1659, which celebrates the end of a plague. Spalla proposes Andrea Solari, [father/brother of Francesco], as the author – See CD – La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi, curated by Floriana Spalla and Ernesto Palmieri produced by La Comunità Montana Lario Intelvese with Appacuvi. Itinerary 2.

2. Giovanni Gavignani’s black and white technique was the predominant means of expression for religious scagliola in Carpi during the 1650s and 60s; the full use of colour did not reappear there until the 1670s and 80s, with the work of Barzelli and Mazelli (see above Chapter 19). (One exception is the strongly coloured altar front in the parish church of San Geminiano in Guiglia, signed and dated 1666 by Simone Setti. a pupil of Gavignani. Setti moved to Modena and is credited by Cabassi with introducing scagliola to the city; he specialised in the production of tabletops for secular clients, normally using his master’s black and white technique to depict classical (as opposed to religious) themes and allegories).

3. See Garuti pp.92-95, also Manni p.23 and Massinelli p.

* Michaela Liebhardt Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts p. 159

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Floriana Spalla Gandola Scagliola Intelvesi, formazione e simbologia (in Imitazione e Belleza) Ghiffa 2004, also See CD – La Scagliola in Valle Intelvi, curated by Floriana Spalla and Ernesto Palmieri produced by La Comunità Montana Lario Intelvese with Appacuvi. Itinerary 2.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152

* Michaela Liebhardt Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts.