The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

A direct Emilian influence on the development of scagliola in northern Italy came from the Leoni brothers, Ludovico and Giovanni. Natives of Carpi, they had both trained under Annibale Griffoni. Early in their careers their father, found guilty of murder, was stripped of his possessions and sentenced to death. He fled the Duchy of Modena and settled in Cremona in Lombardy, taking his family with him. Exactly when this happened is not recorded, and little is known of the brothers’ lives. Giovanni, the younger of the two, was the more accomplished scagliolist.

Ludovico Leoni (Carpi 1637- Cremona 1727)

Before moving to Lombardy, Ludovico had made altar fronts for the church of St. Augustine in Modena (subsequently destroyed in the Napoleonic occupation) and his parents’ family chapel in Carpi (also lost). Having settled in Cremona, he remained there for the rest of a long and active life, producing altar pieces and tabletops.

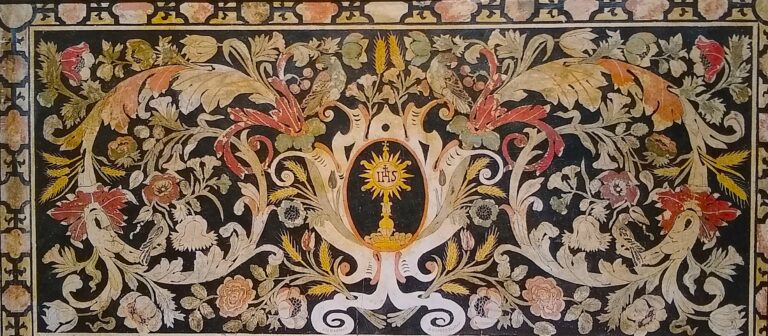

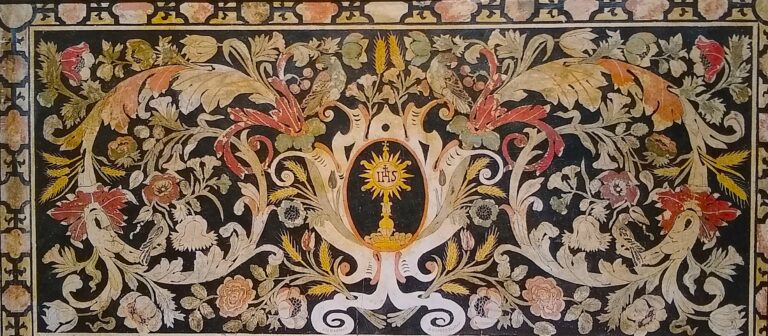

In his early work, rich displays of flowers and foliage surround a central religious symbol or a coat of arms, with an outer border formed from geometrically shaped tiles of imitation marble, a distinctive feature that reappears in both the brothers’ later work.*

The colours are predominantly yellows, oranges and reds on a black background. Several altar pieces in this style have been attributed to Ludovico in the churches of Fidenza, Salsomaggiore and Busseto, as well as Cremona itself.

Altar front in the church of Christo Salvatore in Salsominore (Parma) signed with the name of the donor – R. Paulo Pisseud – and dated 1686. Manni attributes it to Ludovico Leoni on grounds of similarity and proximity to other confirmed work.

* Whether this was the brothers’ own innovation or something they encountered locally and copied is unknown; the use of decorative imitation marble tiles and gemstones recalls the work of Blasius and Wilhelm Fistulator, but more importantly, of inlaid marble work in general. It was popular in Ancient Roman times, where it served a decorative purpose; and in the Christian era, when it relates symbolically to the arrangement of the precious stones that went to make up the Temple of the New Jerusalem, as described in the Apocalypse of St. John.

Ludovico Leoni is also credited with a distinctive series of eight early eighteenth century altar fronts.** Tripartite in design, they feature geometrically shaped panels of different shapes and sizes which contain images of religious figures expressed in an off-white imitation ivory colour, with line drawing and some cross-hatched shading in black. The quality of the shading is not comparable with that of Carpi, and the reliance on line drawing, also used in places to depict swirling ‘ivoried’ foliage, gives these paliotti a less refined appearance than their Emilian counterparts. There are several of these works in the church of San Sepolcro in Piacenza.

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza, showing Santa Barbara in the cetral panel, flanked by two flower vases and angels. (Att. Ludovico Leoni and dated 1716.)

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza. The central panel depicts the Madonna and St. John beside the Crucified Christ. (Att. Ludovico Leoni.)

** None of these works are signed or documented, but Ludovico Leoni’s authorship has been asserted on the basis of anecdote and stylistic similarities. For a full catalogue of Ludovico Leoni’s work in the Cremona region see G. Manni’s I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romana e Marche.

Giovanni Leoni (1639 – early 1700s)

Giovanni Leoni was one of the foremost Carpi-trained scagliolists, and the works of his that have survived are of very high quality. They include several table tops and an altar front, and an outstanding pair of decorative cabinets he made for the royal court of Modena. He appears to have been more involved in secular than religious works, making him unusual for the area.

Like his brother Ludovico, he too worked away from Emilia for most of his life, setting up workshops in Milan and Genoa before eventually moving back to Modena. In 1661, aged twenty one, he signed and dated his earliest surviving work, a tabletop similar in design to the one made by his brother Ludovico in the same decade. In the central panel a parrot perches on a branch, framed by an octagonal border filled with marble tiles. Surrounding this is a symmetrical arrangement of foliage and flowers, and around the edge a border made up of larger marble tiles. The design is elegant and the depiction of the parrot and the flowers naturalistic; an unusual feature is the brightness and strength of the colours, which are quite unlike the subtle shades favoured by the Carpi producers of the period.*

A further work, a small coloured panel (47cms. x 34cms) signed and dated 1668, depicts the Sacred Family and Trinity against a black background; modelling and depth are achieved through a combination of colour and crosshatching. Where the tabletop of 1661 imitates Pietre Dure inlay, this panel is a scagliola painting. The date is well in advance of the scagliola paintings of Pozzuoli and Massa, and shows considerable control and confidence. It is clear that Giovanni Leoni was keen to try new things, and contemporaries considered his work to be distinguished from that of his predecessors and peers by its originality and strangeness (una curiosa bizzarria di ispirazione).**

In 1680-1681 he produced a pair of decorative cabinets with inlaid scagliola panels, made for Prince Ignazio d’Este of Modena. At the time he was living in Milan, from where he sent a letter requesting payment, and describing himself as a maker of furniture (fabricante di scrittori). The two cabinets, signed and dated, are extremely fine and considered his masterpieces. Each one is faced with over twenty scagliola panels of varying shapes and sizes, set in moulded black scagliola frames; they depict conventional Pietre Dure motifs of the day, birds on branches, floral arrangements and marble tiles. A central mirrored cavity is flanked by two inversely tapering pilasters and two salomonic columns, which stand on a scagliola platform inlaid with playing cards. The cabinets are decorated with gilt bronze mountings, and sit on carved timber supports, gessoed to look like ebony.

The design of each panel is finely balanced, and the detailing and naturalism of the birds and flowers is exceptional. The two cabinets are similar in construction and appearance to the Pietre Dure cabinets produced by the Florentine Galleria dei Lavori in the seventeenth century. They are one of the most significant secular commissions of scagliola for the period, and demonstrate the prestige that northern Italian scagliola had achieved by the 1680s. [iii]

In 1683 Giovanni Leoni signed an altar front for the church of San Vittore al Corpo in Milan. In this piece naturalistic foliage and flowers develop from stylised banding which surrounds a central image of an empty Cross; the border is again formed from imitation marble tiles, though in this case the shapes are more varied and interesting. Strong yellows and oranges predominate, balanced by the subtle browns, pinks and greens of the flowers and foliage.

A tabletop signed and dated in Genoa in 1685 (Gio. Leone F. in Genova 1685), now held in the Rijksmueum, Amsterdam, is the last confirmed work of this scagliolist. It was made for the renowned ambassador and scholar Nicolaas Witsen (1641-1717), who was mayor of Amsterdam at the time; his coat of arms, supported by thick acanthus leaves, is in the centre of the table, surrounded by four separate images of birds on flowering branches and two shallow baskets of fruit and flowers. The outer border, set between plain white bands, is filled with a richly portrayed frieze of flowers and fruit. The decorative work, on a black background, is colourful and naturalistic, and once again the table is an impressive example of inlaid scagliola in the style of contemporary Pietre Dure.

The presence in Milan and then Genoa of such a skilled scagliolist with important secular clients both north and south of the Alps encouraged the spread of scagliola throughout the region. Manni sees the influence of Giovanni Leoni in the work of Lorenzo Bonucelli, another scagliolist who was active at the royal court of Turin from the 1680s to the early 1700s (see chapter…).[iv] Neumann connected the development of scagliola production in Lucca and Livorno in the early eighteenth century with Leoni’s presence in Genoa.[v]

[i] Ibid… p. 138-139. The photograph Manni publishes of the tabletop shows it shortly after restoration. Whether the restoration process (or the photo) has restored the colours to their original appearance is impossible to say. They are uncharacteristically bright when compared to other examples of Giovanni Leoni’s work.

[ii] Quoted in Neumann p.

[iii] See Manni pp 140-145 for a full description of these cabinets. In 1870, following the unification of Italy, the cabinets – valued at 20.000 lire – were sent to Vienna as part of an agreement between the commune of Modena and the deposed duke, Francesco V; in return, the commune retained the marble bust of Francesco I by Bernini, which it acknowledged to have been stolen from the d’Este family. The cabinets subsequently disappeared from view and were considered lost. They were rediscovered by Graziano Manni at the end of the last century in the castle of Konopiste in Czeckoslovakia, in remarkably good condition.

[iv] Manni p.146

[v] See Neumann p152

References: For Flowers, Birds and Insects, I am indebted to Silvia Angelini who made available her graduation thesis: Diffusione dei paliotti in scagliola nella Valmarecchia. Università degli Studi di Urbino “Carlo Bo”, Facoltà di lettere e filosofia: 2004-5. Pp 33-40

For Objects and Colours see: Floriana Spalla, Imitazione e Belleza – Opere e tecniche dell’arredo sacro in scagliola, 2003 Ente di Gestione della Riserva Naturale Speciale del Sacro Monte della SS. Trinità di Ghiffa.

Also: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

A direct Emilian influence on the development of scagliola in northern Italy came from the Leoni brothers, Ludovico and Giovanni. Natives of Carpi, they had both trained under Annibale Griffoni. Early in their careers their father, found guilty of murder, was stripped of his possessions and sentenced to death. He fled the Duchy of Modena and settled in Cremona in Lombardy, taking his family with him. Exactly when this happened is not recorded, and little is known of the brothers’ lives. Giovanni, the younger of the two, was the more accomplished scagliolist.

Ludovico Leoni (Carpi 1637- Cremona 1727).

Before moving to Lombardy, Ludovico had made altar fronts for the church of St. Augustine in Modena (subsequently destroyed in the Napoleonic occupation) and his parents’ family chapel in Carpi (also lost). Having settled in Cremona, he remained there for the rest of a long and active life, producing altar pieces and tabletops.

In his early work, rich displays of flowers and foliage surround a central religious symbol or a coat of arms, with an outer border formed from geometrically shaped tiles of imitation marble, a distinctive feature that reappears in both the brothers’ later work.*

The colours are predominantly oranges and reds on a black background. Several altar pieces in this style have been attributed to Ludovico in the churches of Fidenza, Salsomaggiore and Busseto, as well as Cremona itself.

Altar front in the church of Christo Salvatore in Salsominore (Parma) signed with the name of the donor – R. Paulo Pisseud – and dated 1686. Manni attributes it to Ludovico Leoni on grounds of similarity and proximity to other confirmed work.

* Whether this was the brothers’ own innovation or something they encountered locally and copied is unknown; the use of decorative imitation marble tiles and gemstones recalls the work of Blasius and Wilhelm Fistulator, but more importantly, of inlaid marble work in general. It was popular in Ancient Roman times, where it served a decorative purpose; and in the Christian era, when it relates symbolically to the arrangement of the precious stones that went to make up the Temple of the New Jerusalem, as described in the Apocalypse of St. John.

Ludovico Leoni is also credited with a distinctive series of early eighteenth century altar fronts.** Tripartite in design, they feature geometrically shaped panels of different shapes and sizes which contain images of religious figures expressed in an off-white imitation ivory colour, with line drawing and some cross-hatched shading in black. The quality of the shading is not comparable with that of Carpi, and the reliance on line drawing, also used in places to depict swirling ‘ivoried’ foliage, gives these paliotti a less refined appearance than their Emilian counterparts. There are several of these works in the church of San Sepolcro in Piacenza [Photo 15].

** None of these are signed or documented, and Ludovico Leoni’s authorship, which has been asserted on the basis of anecdote and style – similar colouring and the use of imitation marble panels and tiles – is not formally confirmed.

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza, showing Santa Barbara in the cetral panel, flanked by two flower vases and angels. (Att. Ludovico Leoni and dated 1716.)

Altar front in the Parish Church of San Sepolcro, Piacenza. The central panel depicts the Madonna and St. John beside the Crucified Christ. (Att. Ludovico Leoni.)

References: Ornamental Antependiums using Pietra Dure, Scagliola and Stuccolustro, by Heinrich-Joseph Klein, in: Kunstgeschichtliche Aufsatze: Von seinem Schulern und Freunden des KhlK Heinz Ladendorf zum 29.Juni 1969 gewidmet, edited by Joachim Guas, pp. 276-308, Cologne 1969

Next/Chapter 16: The Origins of Italian Scagliola