The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

During his long career at the Munich royal court Blasius Fistulator worked for two Wittelsbach rulers, Duke Wilhelm V (r. 1579-1597 abd.) and Duke/Elector Maximilian I (r. 1597-1651).

Three generations of Wittelsbachs at different ages in their lives: LHS – The future Duke Wilhelm V in 1564 aged 16 (Ambras Castle Innsbruck); RHS – his son, Elector Maximilian I with his son and heir Elector Ferdinand Maria (1636-1679) (Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich)*

The future Duke Wilhelm V in 1564 aged 16 (Ambras Castle Innsbruck)

Duke Wilhelm’s son, Elector Maximilian I with his son and heir Elector Ferdinand Maria (1636-1679).

(Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich)*

We have discussed his earliest work in the previous section: the black scagliola nameplates for the Antiquarium and the first Reiche Kapelle within the old fortified area of the Neuveste. We have also looked at his possible involvement in three table tops that appeared in palaces outside Bavaria at sometime around the turn of the seventeenth century (see Chapters 6 & 8). We can now turn to his other achievements.

Duke Wilhelm’s Table Top

In the early 1590s Duke Wilhelm commissioned a large scagliola table top for his library. It stood on an ornately carved timber support comprising four pairs of legs and three storage cabinets. It was subsequently moved to the Antiquarium by Maximilian I, who used it as a ceremonial dining table; an expensive embroidered cover was specially made for it in 1600.

In his 1644 description of the Munich Residence (see Chapter 9), Baldassare Pistorini mistook this table top for authentic Pietre Dure, stating that it was inlaid with sparkling marbles of many colours enclosing different precious stones, separated by beautiful interlaced designs of arabesque work and foliage. Such a design would have been typical of late sixteenth century Roman or Florentine Pietre Dure work.

Regrettably the table was destroyed when the Residence was bombed in 1944. A black and white photograph exists, but the angle at which it was taken favours the support and reveals little of the top. Dr. Erwin Neumann, who had discussed the piece with the Director of the Munich Residence Museum in the late 1950s, gave the following second-hand description in his article on scagliola:

‘…a decorative table with a scagliola top with geometrical patterns, foliage and vases of flowers; probably designed by Friedrich Sustris, it must have originated in Munich around 1590. If this date were correct (and it related not only to the support but also to the table top), then we would have in this slab the earliest demonstrable example of scagliola ever.’

This black-and-white photograph taken before the 2nd World War is all that remains of a scagliola table top and carved wooden base dating back to c.1590.*

(Dr. Neumann was unaware of the earlier scagliola work in Duke Wilhelm’s original Reiche Kapelle (see chapter 6) which only come to light with Dr. Diemer’s research in the early 2000s).

Other Works and Duke Wilhelm’s Abdication.

Apart from this table top, there is no evidence of other large-scale scagliola work in the time of Duke Wilhelm, though this is not to say that Blasius was inactive during these years, either in his new craft of scagliolist, or his original one of wood-carving and cabinet-making.

The Mercury fountain and grotto (reconstructed). In its day it would have been considerably more colourful and dramatic.* (The Grottenhof, Munich Residence).

Dr. Diemer suggests that Blasius had already been working on the Mercury fountain of the Grottenhof in the late eighties, in particular the grotto itself, using and refining techniques connected with scagliola. The grotto was encrusted with coral (a reference to the Medusa’s blood), sea shells and imitation stones and crystals, all of which would have required pigmented materials to bind them into the background.

The Grottenhof Grotto*(detail)

There is also evidence that he was employed in casting scagliola busts from models and moulds supplied by the sculptor Hubert Gerhard. In 1593 Duke Wilhelm ordered two casts of children’s heads ‘from the hard white material that Blasius makes,’ which were to be polished ‘as if they were Greek marble’.

Duke Wilhelm V abdicated from the throne in 1597. The rigours of government had left him demoralised and ill, afflicted with melancholia (depression) and agonising migraines, which he blamed in part on witchcraft directed against his person. His grandiose building projects, which in addition to the Munich Residence included the massive St. Michael’s Church and the Jesuit College in Munich, and the high cost of financing several Catholic missions to the far East, had bankrupted the court and ruined the economy. It was left to his son Maximilian, already acting as co-regent in the final years of his father’s reign, to restore the state finances and continue the enlargement and modernisation of the Residence. Wilhelm retired to the Palace of Schleissheim where he lived until his death in 1626, devoting himself to religious abstinence and contemplation – albeit in surroundings of some splendour.

Scagliola in the time of Maximilian I (r.1597-1651).

Like his father and grandfather, Maximilian was intensely Catholic. He had been educated at the Jesuit College in Ingolstadt, and was a zealous supporter of the Counter Reformation. He spent much of his reign fighting the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), the disastrous conflict that began as a religious dispute in Bohemia and became what historians have described as the first Pan-European war. Germany was overrun by the armies of the various protagonists, many of them mercenaries who were expected to live off the land; the economy and countryside were devastated and the population reduced by a third or more, with plague and famine the major cause of death. In 1623, as a reward for his efforts on behalf of the Emperor and the Catholic cause in the early years of the war, Maximilian was elevated to the role of Elector. The position was confirmed at the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

The coat-of-arms of Maximilian I of Bavaria, with the electoral insignia of orb and cross. Detail from a scagliola table top by Wilhelm Pfeiffer c. 1630. The Munich Residence.*

During the first twenty years of his reign, Maximilian transformed the Residence from a medieval fortress connected to various disparate buildings into the spectacular palace complex described by Pistorini (see chapter 9). The main building work was completed before the outbreak of the war, though internal decoration, repairs and alterations continued throughout the conflict. Scagliola, now the exclusive property of the newly raised Elector, featured extensively. The material was used for large-scale internal architecture, elaborate inlaid horizontal and vertical surfaces, and smaller decorative objects of virtù.

Inlaid scagliola frame (approx. 55 x 45 cms) by Wilhelm Fistulator, second half 1620s, (the white marble relief depicts ‘Helle and the Ram’ – click to enlarge). Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich*

On his accession to the throne Maximilian had undertaken a complete overhaul of the Bavarian finances. Austerity replaced extravagance, and one of his first acts was to dismiss the team of expensive foreign artists and craftsmen assembled by his father. Blasius was seconded to Scharding, a Wittelsbach posession some 100 miles to the east in Upper Austria, but within a few months he was brought back to Munich. Maximilian had plans for him.

Monumental scagliola in the Antiquarium (c.1597 – 1600).

Blasius’s first commission for the new Duke was the creation of two monumental structures for the end walls of the Antiquarium. Contrasting shades of reddish brown scagliola were used, imitating marble from the Adnet mines near Salzburg; this marble, popular with the Habsburg emperors, can be seen in secular and religious architecture throughout southern Germany and Austria. The same colouring appears in several other works of scagliola in the Residence, matching the Adnet marble frequently used in the floors.

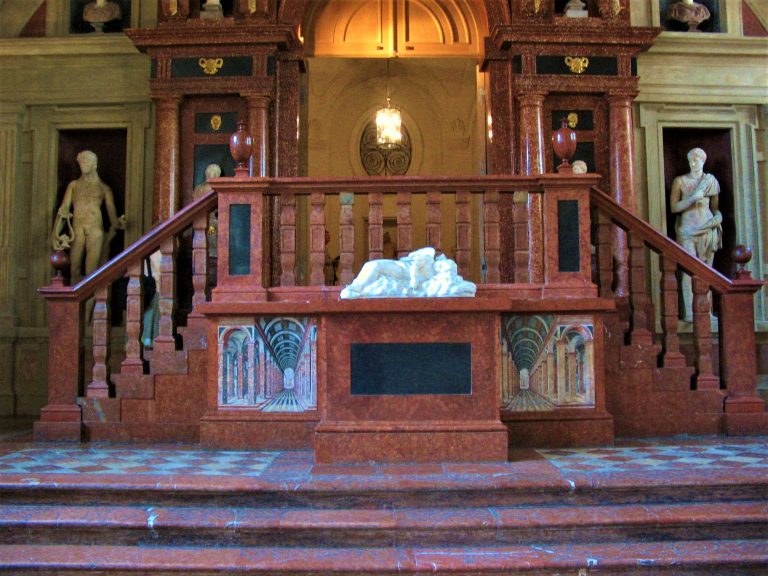

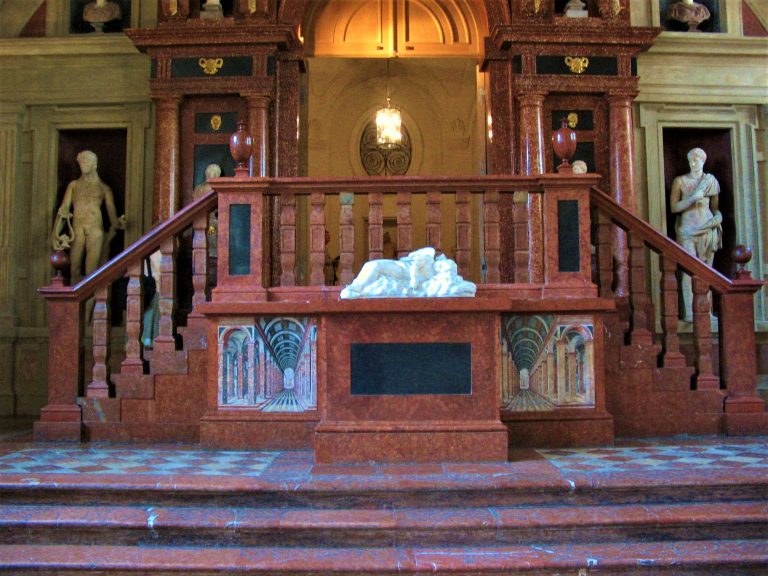

At the north end of the Antiquarium a huge chimney surround with an overmantel and flanking columns was installed to provide a backdrop to the raised and balustraded area used by Maximilian himself during state banquets. (It was here that Blasius’s inlaid scagliola table was kept). The date of completion (M.D.C. – 1600) and Maximilian’s name and title were prominently displayed above the fireplace.

Monumental scagliola chimney surround at the north end of the Antiquarium. The square balustrading, also in scagliola, contained the ducal dining area where the ceremonial table with its scagliola top once stood. (Munich Residence c. 1600. This end of the Antiquarium was the least damaged during the 1944 bombing and some of the scagliola may be original).*

At the south end a musician’s platform backed onto a similar edifice, reminiscent of a Roman triumphal arch. A large doorway raised above the platform was approached from a dais reached by short flights of stairs to left and right. The outer panelling of the stairs, the balusters and the handrails were also made from scagliola.

Scagliola dais and stair rails by Blasius Pfeiffer, 1600. Handed panels with inlaid scagliola architectural perspectives by Wilhelm Pfeiffer c. 1630? The Antiquarium, Munich Residence.*

These two triumphal structures, impressive as they are, seem out of place in Friedrich Sustris’s Italianate hall, but they were a sign of things to come. Their grandiose and austere appearance was a forerunner of the northern mannerist architecture that became fashionable in Germany in the seventeenth century; this was characterised by monumentalism and the experimental use of classical forms to create emotional impact rather than harmony and order. The style was ideally suited to the Wittelsbachs’ imperial pretensions.

At a time when finances were stretched, the use of scagliola made ‘in-house’ to add grandeur to the Antiquarium, and by association the new reign, was an attractive solution. There were problems with the building itself however; the enormous hall was impossible to heat in the winter, when it was most heavily used, and the approach was awkwardly sited for the large processions that preceded royal banquets. In the early years of the seventeenth century, the Hercules Hall on the first floor was refurbished to serve as a banqueting hall, and the Antiquarium returned to its former function as a museum. As a result, the interior decoration was never updated, and its present-day appearance – taking account of post-war reconstruction – is much as it was in 1600.

The Reiche Kapelle (c.1604-1607)

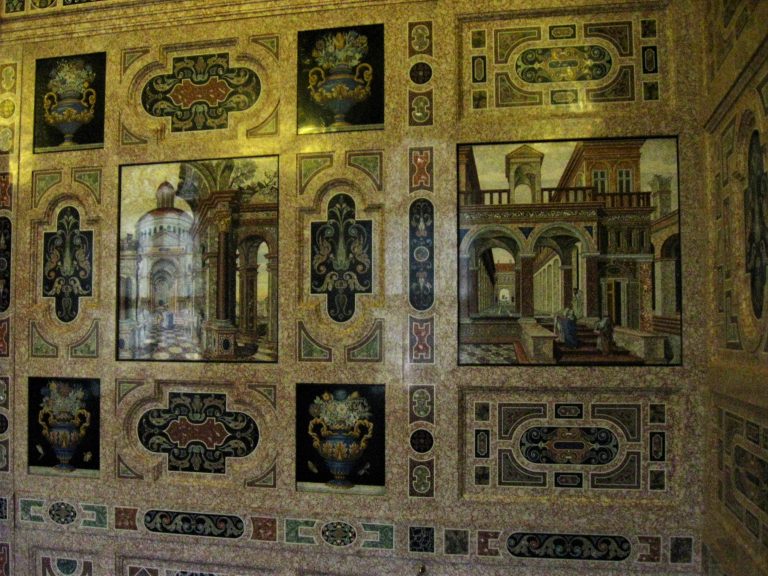

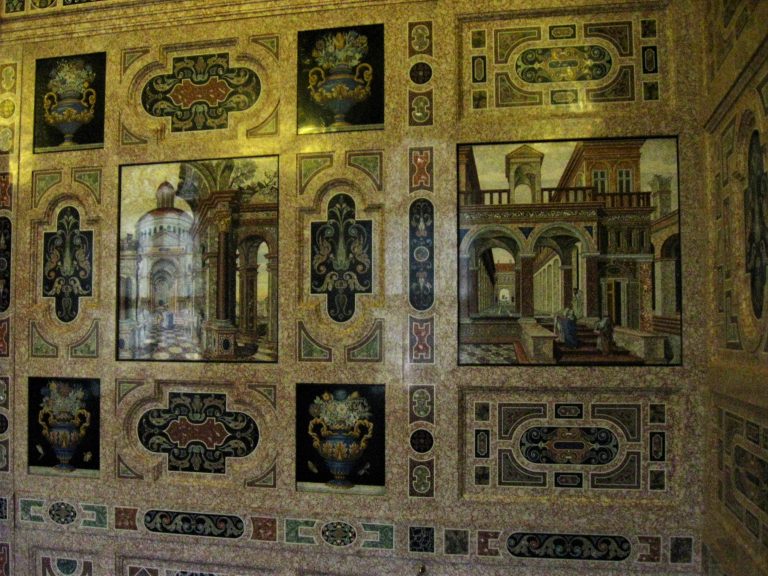

In the early years of the seventeenth century Blasius was commissioned to supply scagliola wall panels for a new Reiche Kapelle to be installed above the Grottenhof. (The chapel that can be seen there today is an accurate post-war copy of this work. The flower vases and the ‘Life of Mary’ pictorial panels, some of which are original, are by Wilhelm Fistulator. They belong to a later period of construction in the early 1630s – see chapter 12).

The Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence c. 1607 (reconstructed 2nd half of the 20th century).*

The repeated use of scagliola wall panelling makes it clear that Maximilian’s chapel was influenced by his father’s; in fact the original panels may well have been removed from the earlier chapel – decommissioned and abandoned soon after Maximilian’s accession – to be reassembled in the later one alongside Wilhelm’s precious collection of relics.

The overall design of the new Reiche Kapelle would have been in the hands of the German sculptor and stuccoist Hans Krumper (c.1570-1634). He had served his apprenticeship with Hubert Gerhard and subsequently worked under Friedrich Sustris, marrying one of his daughters in 1592. He was also a bronze caster, a painter and an occasional architect. When Sustris died in 1598 Krumper succeeded him as artistic director at the Munich court, though in Maximilian’s pared-down Residence the position was never made official, and Krumper only began receiving a fixed salary in 1609.

Blasius’s set of ornamental panels completely cover the wall surfaces from floor to ceiling. The background marbling is an off-white colour with thin reddish-brown veining running throughout. Recessed panels with moulded edges contain inlays of geometrical designs and stylised floral motifs, the latter set into black backgrounds. The inlays, which imitate contemporary Italian Pietre Dure work, are formed from scagliola versions of various marbles and semi-precious stones, such as lapis lazuli, porphyry and verde An inscription above the door records the name of Maximilian and the year 1607, the date of the chapel’s consecration.

Scagliola panelling on the right-hand side wall of the Reiche Kapelle. Background and geometrically patterned panels by Blasius Fistulator c. 1607, Flower Vases and pictorial panels by Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1630 .*

These inlaid panels were bravura pieces by Blasius, and the confidence and precision of their execution is outstanding. There is first-hand evidence of the success of the work in the diaries of Phillip Hainhoffer (1578-1647), a widely travelled merchant, collector and connoisseur from Augsburg, who served as agent and ambassador to many of the German princes, including the Wittelsbachs, for whom he was a trusted friend and adviser. They were prepared to overlook his protestant religion, since it enabled him to act as a go-between with those German courts that had renounced Catholicism. (Among the other services he could offer was that of intermediary in the disposal of sacred relics, no longer considered appropriate for protestant courts). Hainhoffer had his own Wunderkammer, which was visited by many of Europe’s rulers, including Maximilian’s father, Wilhelm. His diaries serve as an important contemporary source for art historians of the period.

Devotional sculpture and reliquary wall cabinets in the Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence (1st half 17th Century?)*

Like all collectors from this period, Hainhoffer was fascinated by hardstones and what could be done with them. After visiting the Reiche Kapelle in 1611, he wrote in his diary:

‘The vault and walls are beautiful…white with various colours of cast and polished plaster, so that [even] the emperor’s stone-cutters were apparently deceived, thinking it was beautifully inlaid with natural precious stones….’

Whether such experienced stone-cutters as the Castrucci were really taken in by the deception, or whether this was merely a story going the rounds, is open to conjecture. True or false, the claim itself can only have increased interest in the new material.

Just as important was the approval of Hainhoffer himself; with his contacts throughout Europe, he was able to spread the news about scagliola. In 1612, a year after visiting the Reiche Kapelle, he acted as go-between for the gift of an inlaid scagliola tabletop from the abdicated Duke Wilhelm to Duke Phillip II of Pomerania-Stettin; like the tabletop that now sat in the Munich Antiquarium, it was intended to serve as a ceremonial dining table. Such a gift conferred prestige on both giver and recipient, and of course on the strange and exclusive material from which it was made. (See References for further information on Hainhoffer’s contacts).

The court documents for 1607 record an ex-gratia payment of 200 guilders to Blasius for his ‘faithful labours’. This amount was equal to his annual salary, which itself was now increased to 300 guilders.

Detail of scagliola doorway with broken pediment and inlays by Blasius Fistulator. Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence c. 1607*

The Imperial Courtyard (c. 1611-1619)

The buildings that surround the Imperial Courtyard were originally constructed in the second decade of the 1600s as part of a major initiative to increase the size and prestige of the Residence. This had become possible as a result of Duke Maximilian’s restructuring of the Bavarian economy and finances. The west and east ranges of the courtyard each contained an important suite of apartments, known respectively as the Stone Rooms and the Trier Rooms. The north range was given over to the Imperial Staircase, the Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room. All these areas were strongly representational, and all featured scagliola in both its forms.

The Stone Rooms.

Originally called the Imperial Rooms (Die Kaiserzimmer), these rooms were the most sumptuous in Maximilian’s Residence. Amongst other treasures they contained an outstanding display of tapestries depicting the achievements of the founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty, Count Palatine Otto I (1117-1183). These were made by the Dutch tapestry weaver Hans van der Biest from designs by the Flemmish artist Peter Candid.

The Stone Rooms (detail): One of a set of tapestries made by the Dutchman Hans van der Biest (early 17th century). The door surround and window reveal are made from scagliola.*

The apartment, comprising six consecutive rooms, was reserved for the sole use of the Emperor and his consort should they choose to visit Munich. Such an honour was by no means unlikely; family and marriage ties were strong between the Habsburgs and the Wittelsbachs, and Munich was a convenient stopping-off place for Frankfurt and Augsburg, where imperial coronations were held. In the event the desired visit never occurred during Maximilian’s reign; presumably the war made it impossible.

Blasius Fistulator, now assisted by his sons Wilhelm (b. 1590) and Paul (first doc. 1607), was commissioned to create an imposing set of scagliola doorways with elaborate pediments, in line with the prevailing taste for monumental marble architecture. The background colours of these doorways were made up from combinations of red and grey marbles and granites, inlaid with geometrically shaped polychromatic panels, similar in style to the Reiche Kapelle. Inside the rooms there were scagliola chimney pieces, window surrounds and wall panelling.

The Stone Rooms (details): scagliola mouldings and internal architecture (orig. 1610-1620; re-instated 1675-1700 and again in the second half of the 20th century. Click on images to enlarge).*

The Stone Rooms (details): scagliola mouldings and internal architecture (orig. 1610-1620; re-instated 1675-1700 and again in the second half of the 20th century).*

A description of the Stone Rooms written in 1661 by an unknown visitor (the original is in French) reads as follows:

‘the apartment which is destined for the Emperor should he come to Munich, is remarkable, and I do not think that one could see its like, not only in Germany but also in France and Italy. All the doors of the said apartment are made up from different elements and the doorways of a very beautiful marble, enriched with an infinite number of fine and precious stones which form one thousand pretty pictures…’

The Trier Rooms

The Trier Rooms were named after the Saxon elector of Trier, who stayed there for long periods in the eighteenth century. They were originally known as the Royal Rooms (Königlich-Zimmer), and were intended for foreign princes who were passing through Munich.

Although less grand than the Stone Rooms, these too were designed to impress, forming an enfilade that ran the length of the east side of the Emperor’s Courtyard, with a series of closely aligned door surrounds. (The original lay-out for these rooms provided for two separate apartments, one for the dignitary and the other for his consort; a middle room served as a meeting point between the two). The surrounds were all made from a reddish brown scagliola flecked with grey-white veining, imitating a variety of Adnet marble.

The Trier Rooms: LHS: the enfilade of doorways in matching ‘Adnet’ scagliola. RHS: Closed doorway with scagliola surround. (Original 1610-1620/re-instated 2nd half 20th century. Click on images to enlarge)*

The Trier Rooms: Top: the enfilade of doorways in matching ‘Adnet’ scagliola. Bottom: Closed doorway with scagliola surround. (Original 1610-1620/re-instated 2nd half 20th century).*

Two of these rooms were decorated with richly inlaid scagliola wall panels similar in style to those in the Reich Kapelle. In the 1720s these panels were taken down and reinstated in the new palace of Schleissheim, where they can still be seen today (see Home page). Until the mid-twentieth century they were considered to be the work of Blasius Pfeiffer, but the inscription ‘16WF29’ discovered on the back of one of the panels suggests that they were made in 1629 by his son Wilhelm (see chapter 11).

The Imperial Stairway.

The approach to the Stone Rooms and the Trier Rooms was by way of the Imperial Stairway, finished in the same period (c. 1616). The top of this staircase was flanked on its open side by two pairs of free-standing Tuscan columns set on pedestal bases linked by a balustrade and handrail. The columns and capitals were made in scagliola, the pedestals and balustrade in marble.

Opposite, on the closed side of the stair, matching pilasters and pedestals were engaged in the wall, the colours once again of a reddish-brown with off-white veining and large grey streaks. Three monumental stucco figures made by Hans Krumper stood in stucco-decorated wall niches, emphasising the stairway’s imperial connotations: they depict Otto von Wittelsbach (founder of the dynasty – see above), Emperor Charlemagne and Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian (r. as Holy Roman Emperor 1328-1347).

The Imperial Stairway with scagliola columns and pilasters. The statues are by Hans Krumper. (original 1610-1616/re-instated 2nd half 20th century).*

The Imperial Hall.

At the top of the stairway three scagliola-framed doorways led into the Imperial Hall. On the inside wall of the arched central opening a monumental scagliola structure was formed from fluted pilasters and plain columns set on pedestal bases. These supported a broken pediment with amphorae at the sides and the Wittelsbach coat of arms mounted on an elaborately carved panel in the centre. The background colour was a brownish pink mottled with grey; the columns were black, their lower sections inlaid with Pietre Dure designs.

The Imperial Hall: View through the scagliola central doorway towards the top of the Imperial Stairway (blt. 1612-1616: replaced 1799: re-instated 2nd half 20th century)*

At the far end of the hall a reflecting structure with identical black columns and pediment surrounded the fireplace. A large black niche above the fireplace originally held a porphyry coloured stucco (probably scagliola) statue of Virtue. The four smaller doorways in the Emperor’s Hall were also decorated with scagliola surrounds, as were the mouldings on the walls (cornices, architraves, picture frames etc.).

The Imperial Hall: Top: view towards the fireplace and doorway into the Four Greys Room. Bottom: Scagliola column detail with inlays).*

The Imperial Hall: LHS view towards the fireplace and doorway into the Four Greys Room. RHS Scagliola column detail with inlays. (Click on images to enlarge)*

Like the Stone Rooms, the walls of the Imperial Hall were hung with tapestries designed by Peter Candid and created by Hans van der Biest. They depicted various figures from Antiquity and the Old Testament, who were seen as role models for princely rule.

As its name suggests, the Imperial Hall was one of the grandest rooms in Maximilian’s Residence. The use of scagliola to create monumental architecture recalls the Antiquarium – whose ceremonial function it replaced – and once again underlines its acceptance as a prestigious material.

(The Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room (see below) were remodelled in the early years of the 19th century to provide private apartments for Elector Maximilian IV. It was only during the full-scale reconstruction program after the second world war that the decision was taken to reinstate the original 17th century scheme; this had to be created from historical documents and sources, but without the benefit of photographic records or living memory.)

The Four Greys Room

This room, another 20th century reconstruction, was named after its original ceiling painting which showed Apollo in his chariot being drawn by four white horses; it stands between the far end of the Imperial hall and the Stone Rooms. Its main function was to serve as an antechamber and private dining-room when the Stone Rooms were occupied. Its most important scagliola feature was a pictorial work by Wilhelm Fistulator, which will be discussed in Chapter 12.

The Four Greys Room, named after a former ceiling painting of Apollo in his chariot (blt. 1612-1616: replaced 1799: re-instated 2nd half 20th century)*

The Black Room (c.1610-1620)

Wilhelm V had this room installed in the early 1590s. It stood at the top of a flight of stairs on the upper floor of a new construction built onto the east end of the Antiquarium, where it served as a reception area for various apartments in the old Residence. It also gave access to the ducal library which was situated above the Antiquarium.

Early in the new reign (c. 1600) the room was remodelled and the ceiling raised to create space for an illusionistic architectural painting by the Munich born artist Hans Werl (1570-1609). In the following decade four black scagliola portals were installed, giving the room its name (der Schwarze Saal). They were decorated with sunken panels depicting various marbles, and although the quality of the latter is not of the highest, these jet black portals (imitating Belgian Black marble) are very striking.

The Black Room: Top: two of the four black scagliola door portals. Bottom:upper section and pediment with inlaid panels (blt. and restructured 1590s-1620, re-instated 2nd half 20th Century).*

The Black Room: LHS two of the four black scagliola door portals; RHS upper section and pediment with inlaid panels (blt. and restructured 1590s-1620, re-instated 2nd half 20th Century. Click on images to enlarge)*

A large matching chimney piece made by Wilhelm Fistulator was added in the 1620s. It supported an impressive over-mantel displaying the Wittelsbach coat of arms flanked by two gilded figures, the ensemble probably carved in wood.

Scagliola Perspectives in the Western Grottenhall (pre 1611).

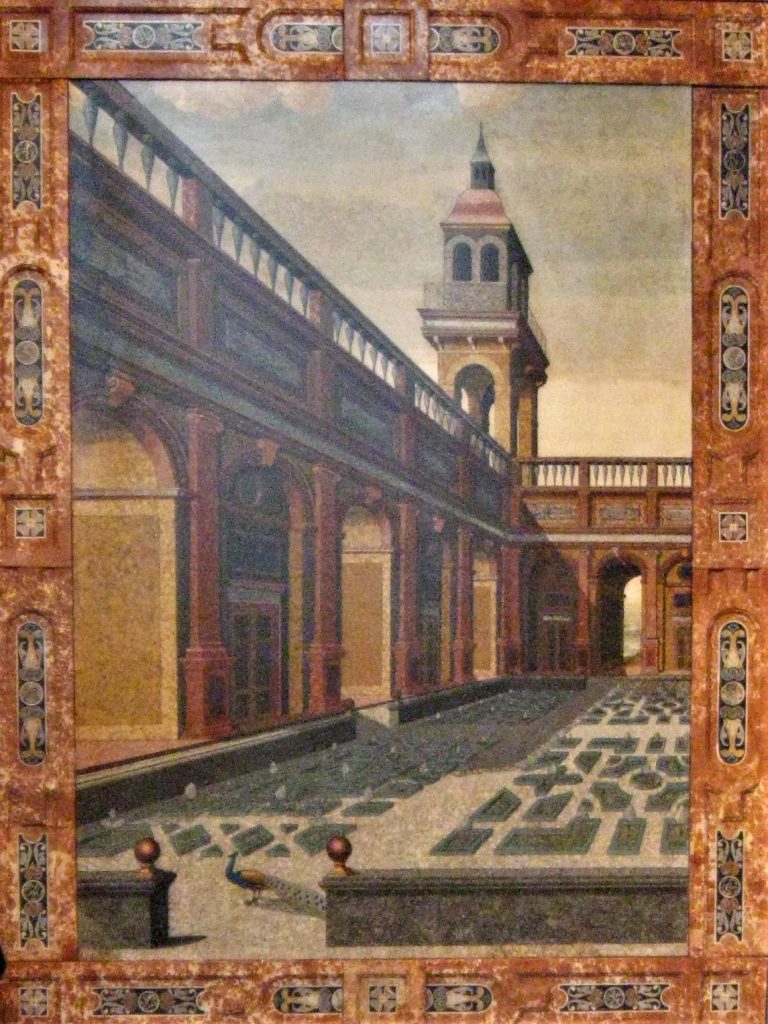

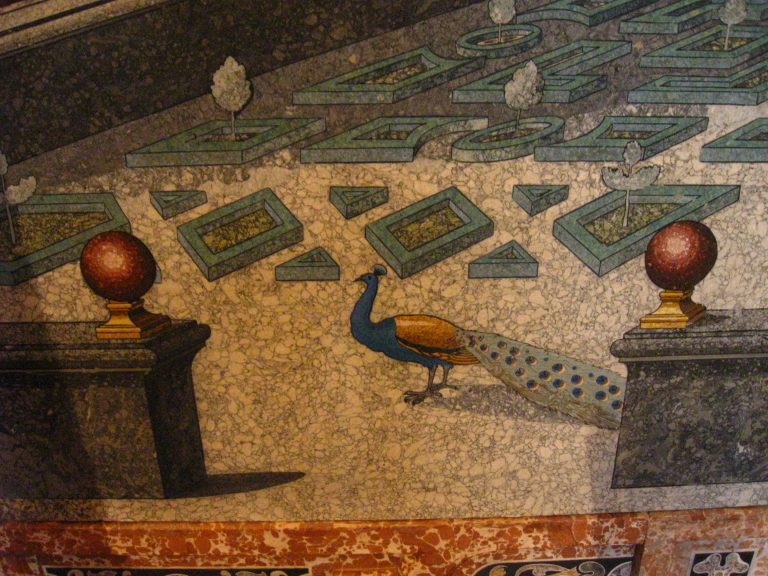

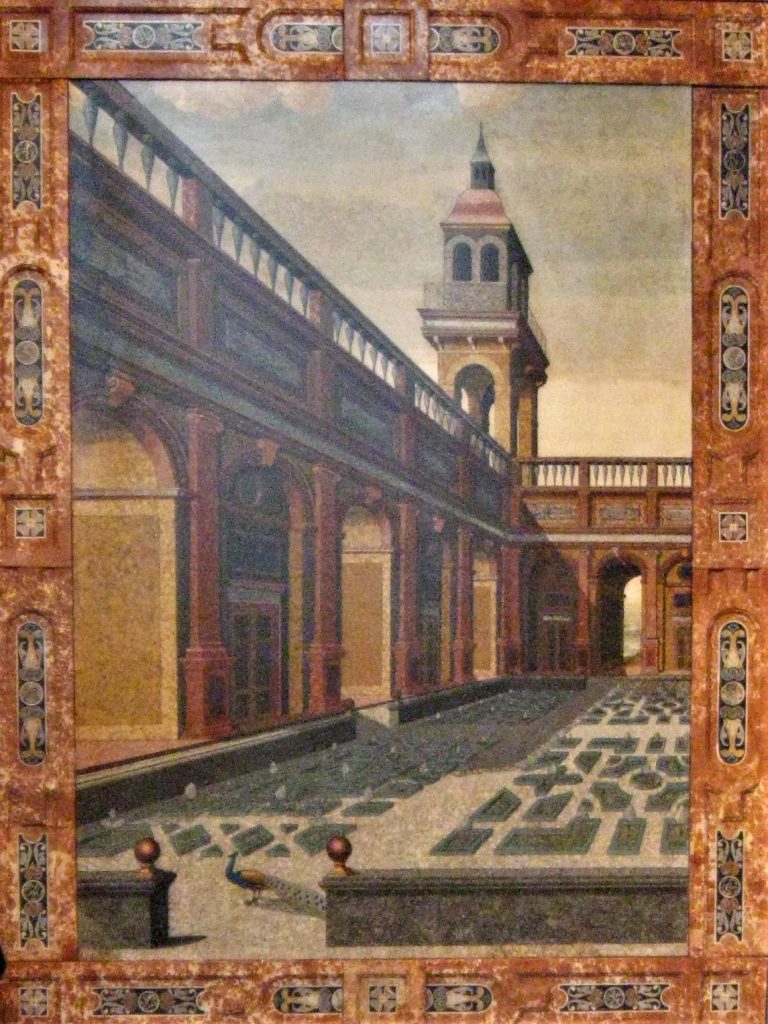

Michaela Liebhardt gives anecdotal evidence of ten scagliola pictorial perspectives on the walls of the western Grotto Hall. The Grottenhalle was a loggia that took up the ground floor of the west range of the Grotto Courtyard, opposite the colonnaded area of the east range that housed the grotto itself.

In the diary entries covering his visit to the Munich Residenz in 1611, Phillip Hainhoffer described the walls of the open-sided hall as being coloured in the style of the Reiche Kapelle and the table in the Antiquarium (made for Prince Wilhelm in the 1590s – see above).

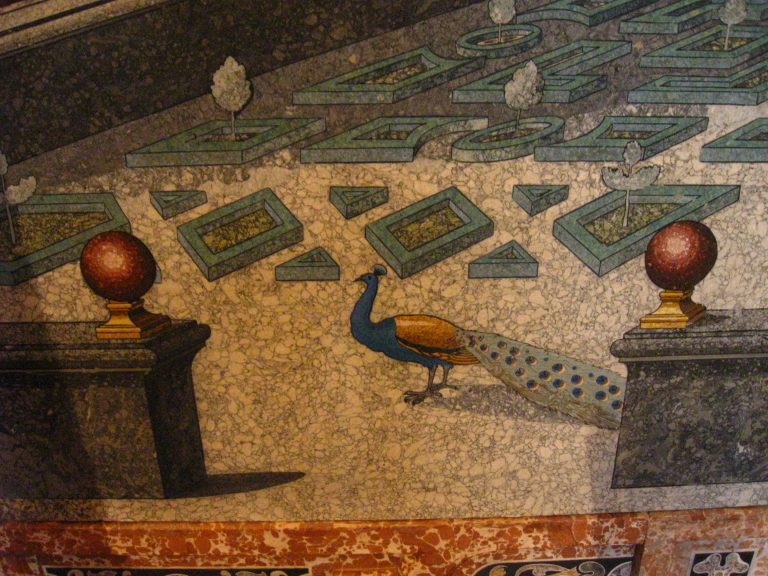

A French visitor, the Baron de Moncorny, recorded that during his visit to the Residence in 1664 the panels in the Garden Hall were covered up to protect them from the weather; and in 1667 the Italian Cardinal Ranuzzio Pallavacino (who studied for a while in Munich alongside Crown Prince Ferdinand-Maria of Bavaria) mentioned the loggias (plural?) covered with perspective scenes (lunghissima veduta).

A palace inventory of ‘Scagliolaarbeiten’ (scagliola works) taken in 1707 recorded the existence of ten Perspectives in the stone garden opposite the coral fountain (i.e. the Grotto fountain). In the same year the Residence’s concierge (Burgpfleger) wrote of the ornate perspectives made from rare marble work in the Sala Terena (Garden Room); a final mention came in 1719 from a Christoph Kalmbach, yet another visitor to the Residence who was greatly impressed.

A scagliola architectural perspective of the type that would have decorated the Western Grottenhall of the Munich Residence. Similar in style to Wilhelm Fistulator’s pictorial work, it is less sophisticated than his earlier ‘Life of Mary’ sequence in the Reiche Kapelle, and may have been a workshop piece. (Bavarian National museum, Munich c. 1640)*

In 1730 the facades of the Grotto Courtyard were altered by the Rococo designer Francois de Cuvilliés (1695-1768). The western Grotto Hall was closed in and the scagliola perspectives disappeared. There are no detailed descriptions of their appearance, though there are plenty of other examples of architectural perspectives in scagliola that have survived in the Residence and elsewhere. They are largely the work of Wilhem Fistulator and his workshop, and will be examined in Chapter 12.

(Liebhardt believed that the 1611 sighting by Hainhoffer implied that Blasius Fistulator was responsible for the work. This seems unlikely on two counts; firstly, there are no other examples of pictorial work by Blasius; and secondly, Hainhoffer’s description likens the work to the Reiche Kapelle as it was in 1611, before the pictorial additions by Wilhelm in the late 1620s. The most likely explanation is that (as in the Reiche Kapelle) Blasius supplied the initial decorative scagliola in the first decade of the century, and his son Wilhelm added the ten perspectives at a later date.)

Detail from Panel

Postscript: Damage and Reconstruction in the Munich Residence.

Almost everything that Blasius Fistulator made for the Munich Residence was subsequently destroyed, and what is seen of his work today is in fact a series of remarkable 20th century reconstructions.

Serious fires between 1674 and 1750 destroyed what was left of Duke Wilhelm’s original Reiche Kapelle (blt. 1585-1590 and subsequently abandoned by his son Maximilian) and, more importantly, the Stone Rooms (blt.1611-1619). The latter were rebuilt in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room were remodelled in 1779 to create the Court Garden Rooms, a range of neoclassical apartments for Max I Joseph and his wife Karoline von Baden.

Destruction of a different order occurred in April 1944, when the Residence was hit in Munich’s worst bombing raid of the Second World War. The building was gutted by fire, and further bombing and bad weather added to the destruction; stucco and scagliola work suffered particularly badly.

The Munich Residence after 2nd World War bomb damage. From the top, Nos. 1 & 2: The Reiche Kapelle. No. 3: The Trier Rooms. (Photos 1-3 are dated 24th April 1944. They were kindly provided by the Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung). No. 4: The Antiquarium before and after reconstruction.*

The Munich Residence after 2nd World War bomb damage. Top LHS & RHS: The Reiche Kapelle. Bottom LHS: The Trier Rooms (These photos are dated 24th April 1944. They were kindly provided by the Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung). Bottom RHS: The Antiquarium before and after reconstruction.*

The decision was taken to rebuild, and construction began in 1945 and continued into the twenty-first century. Many of the original interiors were recreated, with meticulous attention paid to records and photographs. Not everything had been lost; at the start of the war all removable art works were stored off-site, including important scagliola pictures and tabletops. By good fortune the wall panelling made for the Trier rooms in the late 1620’s had been moved to the new palace at Schleissheim in the 1720’s, and came through the war unscathed. Six of Wilhelm Fistulator’s pictorial ‘Life of Mary’ panels from the Reiche Kapelle also survived, as did various pieces made as gifts for other destinations (including the Imperial Court in Vienna). Thus there were many original examples to copy, and comparisons between old and new show that this was done with considerable skill and accuracy.

The reconstruction and re-reinstatement of the Munich Residence is a significant event in the history of scagliola, and will be covered in a subsequent chapter.

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze,

References:

Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon München: K.G. Saur, 1992- c2011 (supercedes Thieme-Becker).

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.

Michaela Liebhardt, Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987 – Liebhardt catalogues all the scagliola activity at the Munich Residence in the 17th and early 18th centuries making use of surviving court documents, correspondence, inventories and accounts. (The quotes in this chapter are taken from Liebhardt unless otherwise stated).

Dorothea Diemer, Hubert Gerhard und Carlo di Cesare del Palagio Berlin 2004

For Hainhoffer’s circle of contacts, see: Philipp Hainhoffer and Gustavus Adolphus’s Kunstschrank in Uppsala by Hans-Olaf Boström pp. 90-92 in Origins of Museums ed. O.Impey and A Macgregor – Clarendon Press – Oxford 1985. Hainhoffer’s royal and aristocratic contacts were considerable. In addition to a number of German princes, Boström names: King Christian IV of Denmark, Archduke Leopold V of Austria, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (for whom Hainhoffer arranged the making of the Uppsala Künstschrank), the Elector Palatine Frederic V, various Medici Princes, and some travelling English aristocrats, the most distinguished of whom was Thomas Howard, second Earl of Arundel.

During his long career at the Munich royal court Blasius Fistulator worked for two Wittelsbach rulers, Duke Wilhelm V (r. 1579-1597 abd.) and Duke/Elector Maximilian I (r. 1597-1651). We have discussed his earliest work in the previous section: the black scagliola nameplates for the Antiquarium and the first Reiche Kapelle within the old fortified area of the Neuveste. We have also looked at his possible involvement in three table tops that appeared in palaces outside Bavaria at sometime around the turn of the seventeenth century (see Chapters 6 & 8). We can now turn to his other achievements.

Duke Wilhelm’s Table Top

In the early 1590s Duke Wilhelm commissioned a large scagliola table top for his library. It stood on an ornately carved timber support comprising four pairs of legs and three storage cabinets. It was subsequently moved to the Antiquarium by Maximilian I, who used it as a ceremonial dining table; an expensive embroidered cover was specially made for it in 1600.

In his 1644 description of the Munich Residence (see Chapter 9), Baldassare Pistorini mistook this table top for authentic Pietre Dure, stating that it was inlaid with sparkling marbles of many colours enclosing different precious stones, separated by beautiful interlaced designs of arabesque work and foliage. Such a design would have been typical of late sixteenth century Roman or Florentine Pietre Dure work.

Regrettably the table was destroyed when the Residence was bombed in 1944. A black and white photograph exists, but the angle at which it was taken favours the support and reveals little of the top. Dr. Erwin Neumann, who had discussed the piece with the Director of the Munich Residence Museum in the late 1950s, gave the following second-hand description in his article on scagliola:

‘…a decorative table with a scagliola top with geometrical patterns, foliage and vases of flowers; probably designed by Friedrich Sustris, it must have originated in Munich around 1590. If this date were correct (and it related not only to the support but also to the table top), then we would have in this slab the earliest demonstrable example of scagliola ever.’

(Dr. Neumann was unaware of the earlier scagliola work in Duke Wilhelm’s original Reiche Kapelle (see chapter 6) which only come to light with Dr. Diemer’s research in the early 2000s).

Other Works and Duke Wilhelm’s Abdication.

Apart from this table top, there is no evidence of other large-scale scagliola work in the time of Duke Wilhelm, though this is not to say that Blasius was inactive during these years, either in his new craft of scagliolist, or his original one of wood-carving and cabinet-making.

Dr. Diemer suggests that Blasius had already been working on the Mercury fountain of the Grottenhof in the late eighties, in particular the grotto itself, using and refining techniques connected with scagliola. The grotto was encrusted with coral (a reference to the Medusa’s blood), sea shells and imitation stones and crystals, all of which would have required pigmented materials to bind them into the background.

There is also evidence that he was employed in casting scagliola busts from models and moulds supplied by the sculptor Hubert Gerhard. In 1593 Duke Wilhelm ordered two casts of children’s heads ‘from the hard white material that Blasius makes,’ which were to be polished ‘as if they were Greek marble’.

Duke Wilhelm V abdicated from the throne in 1597. The rigours of government had left him demoralised and ill, afflicted with melancholia (depression) and agonising migraines, which he blamed in part on witchcraft directed against his person. His grandiose building projects, which in addition to the Munich Residence included the massive St. Michael’s Church and the Jesuit College in Munich, and the high cost of financing several Catholic missions to the far East, had bankrupted the court and ruined the economy. It was left to his son Maximilian, already acting as co-regent in the final years of his father’s reign, to restore the state finances and continue the enlargement and modernisation of the Residence. Wilhelm retired to the Palace of Schleissheim where he lived until his death in 1626, devoting himself to religious abstinence and contemplation – albeit in surroundings of some splendour.

Scagliola in the time of Maximilian I (r.1597-1651).

Like his father and grandfather, Maximilian was intensely Catholic. He had been educated at the Jesuit College in Ingolstadt, and was a zealous supporter of the Counter Reformation. He spent much of his reign fighting the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), the disastrous conflict that began as a religious dispute in Bohemia and became what historians have described as the first Pan-European war. Germany was overrun by the armies of the various protagonists, many of them mercenaries who were expected to live off the land; the economy and countryside were devastated and the population reduced by a third or more, with plague and famine the major cause of death. In 1623, as a reward for his efforts on behalf of the Emperor and the Catholic cause in the early years of the war, Maximilian was elevated to the role of Elector. The position was confirmed at the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

***

During the first twenty years of his reign, Maximilian transformed the Residence from a medieval fortress connected to various disparate buildings into the spectacular palace complex described by Pistorini (see chapter 9). The main building work was completed before the outbreak of the war, though internal decoration, repairs and alterations continued throughout the conflict. Scagliola, now the exclusive property of the newly raised Elector, featured extensively. The material was used for large-scale internal architecture, elaborate inlaid horizontal and vertical surfaces, and smaller decorative objects of virtù.

On his accession to the throne Maximilian had undertaken a complete overhaul of the Bavarian finances. Austerity replaced extravagance, and one of his first acts was to dismiss the team of expensive foreign artists and craftsmen assembled by his father. Blasius was seconded to Scharding, a Wittelsbach posession some 100 miles to the east in Upper Austria, but within a few months he was brought back to Munich. Maximilian had plans for him.

Monumental scagliola in the Antiquarium (c.1597 – 1600).

Blasius’s first commission for the new Duke was the creation of two monumental structures for the end walls of the Antiquarium. Contrasting shades of reddish brown scagliola were used, imitating marble from the Adnet mines near Salzburg; this marble, popular with the Habsburg emperors, can be seen in secular and religious architecture throughout southern Germany and Austria. The same colouring appears in several other works of scagliola in the Residence, matching the Adnet marble frequently used in the floors.

At the north end of the Antiquarium a huge chimney surround with an overmantel and flanking columns was installed to provide a backdrop to the raised and balustraded area used by Maximilian himself during state banquets. (It was here that Blasius’s inlaid scagliola table was kept). The date of completion (M.D.C. – 1600) and Maximilian’s name and title were prominently displayed above the fireplace. At the south end a musician’s platform backed onto a similar edifice, reminiscent of a Roman triumphal arch. A large doorway raised above the platform was approached from a dais reached by short flights of stairs to left and right. The outer panelling of the stairs, the balusters and the handrails were also made from scagliola.

These two triumphal structures, impressive as they are, seem out of place in Friedrich Sustris’s Italianate hall; but they were a sign of things to come. Their grandiose and austere appearance was a forerunner of the northern mannerist architecture that became fashionable in Germany in the seventeenth century; this was characterised by monumentalism and the experimental use of classical forms to create emotional impact rather than harmony and order. The style was ideally suited to the Wittelsbachs’ imperial pretensions.

At a time when finances were stretched, the use of scagliola made ‘in-house’ to add grandeur to the Antiquarium, and by association the new reign, was an attractive solution. There were problems with the building itself however; the enormous hall was impossible to heat in the winter, when it was most heavily used, and the approach was awkwardly sited for the large processions that preceded royal banquets. In the early years of the seventeenth century, the Hercules Hall on the first floor was refurbished to serve as a banqueting hall, and the Antiquarium returned to its former function as a museum. As a result, the interior decoration was never updated, and its present-day appearance – taking account of post-war reconstruction – is much as it was in 1600.

The Reiche Kapelle (c.1604-1607)

In the early years of the seventeenth century Blasius was commissioned to supply scagliola wall panels for a new Reiche Kapelle to be installed above the Grottenhof. (The chapel that can be seen there today is an accurate post-war copy of this work. The flower vases and the ‘Life of Mary’ pictorial panels, some of which are original, are by Wilhelm Fistulator. They belong to a later period of construction in the early 1630s – see chapter 12).

The repeated use of scagliola wall panelling makes it clear that Maximilian’s chapel was influenced by his father’s; in fact the original panels may well have been removed from the earlier chapel – decommissioned and abandoned soon after Maximilian’s accession – to be reassembled in the later one alongside Wilhelm’s precious collection of relics.

The overall design of the new Reiche Kapelle would have been in the hands of the German sculptor and stuccoist Hans Krumper (c.1570-1634). He had served his apprenticeship with Hubert Gerhard and subsequently worked under Friedrich Sustris, marrying one of his daughters in 1592. He was also a bronze caster, a painter and an occasional architect. When Sustris died in 1598 Krumper succeeded him as artistic director at the Munich court, though in Maximilian’s pared-down Residence the position was never made official; in fact Krumper did not even begin to receive a fixed salary until 1609.

Blasius’s set of ornamental panels completely cover the wall surfaces from floor to ceiling. The background marbling is an off-white colour with thin reddish-brown veining running throughout. Recessed panels with moulded edges contain inlays of geometrical designs and stylised floral motifs, the latter set into black backgrounds. The inlays, which imitate contemporary Italian Pietre Dure work, are formed from scagliola versions of various marbles and semi-precious stones, such as lapis lazuli, porphyry and verde antico. An inscription above the door records the name of Maximilian and the year 1607, the date of the chapel’s consecration.

These inlaid panels were bravura pieces by Blasius, and the confidence and precision of their execution is outstanding. There is first-hand evidence of the success of the work in the diaries of Phillip Hainhoffer (1578-1647), a widely travelled merchant, collector and connoisseur from Augsburg, who served as agent and ambassador to many of the German princes, including the Wittelsbachs, for whom he was a trusted friend and adviser. They were prepared to overlook his protestant religion, since it enabled him to act as a go-between with those German courts that had renounced Catholicism. (Among the other services he could offer was that of intermediary in the disposal of sacred relics, no longer considered appropriate for protestant courts). Hainhoffer had his own Wunderkammer, which was visited by many of Europe’s rulers, including Maximilian’s father, Wilhelm. His diaries serve as an important contemporary source for art historians of the period.

Like all collectors from this period, Hainhoffer was fascinated by hardstones and what could be done with them. After visiting the Reiche Kapelle in 1611, he wrote in his diary:

‘The vault and walls are beautiful…white with various colours of cast and polished plaster, so that [even] the emperor’s stone-cutters were apparently deceived, thinking it was beautifully inlaid with natural precious stones….’

Whether such experienced stone-cutters as the Castrucci were really taken in by the deception, or whether this was merely a story going the rounds, is open to conjecture. True or false, the claim itself can only have increased interest in the new material.

Just as important was the approval of Hainhoffer himself; with his contacts throughout Europe, he was able to spread the news about scagliola. In 1612, a year after visiting the Reiche Kapelle, he acted as go-between for the gift of an inlaid scagliola tabletop from the abdicated Duke Wilhelm to Duke Phillip II of Pomerania-Stettin; like the tabletop that now sat in the Munich Antiquarium, it was intended to serve as a ceremonial dining table. Such a gift conferred prestige on both giver and recipient, and of course on the strange and exclusive material from which it was made. (See References for further information on Hainhoffer’s contacts).

The court documents for 1607 record an ex-gratia payment of 200 guilders to Blasius for his ‘faithful labours’. This amount was equal to his annual salary, which itself was now increased to 300 guilders.

The Imperial Courtyard (c. 1611-1619)

The buildings that surround the Imperial Courtyard were originally constructed in the second decade of the 1600s as part of a major initiative to increase the size and prestige of the Residence. This had become possible as a result of Duke Maximilian’s restructuring of the Bavarian economy and finances. The west and east ranges of the courtyard each contained an important suite of apartments, known respectively as the Stone Rooms and the Trier Rooms. The north range was given over to the Imperial Staircase, the Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room. All these areas were strongly representational, and all featured scagliola in both its forms.

The Stone Rooms.

Originally called the Imperial Rooms (Die Kaiserzimmer), these rooms were the most sumptuous in Maximilian’s Residence. Amongst other treasures they contained an outstanding display of tapestries depicting the achievements of the founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty, Count Palatine Otto I (1117-1183). These were made by the Dutch tapestry weaver Hans van der Biest from designs by the Flemmish artist Peter Candid.

The apartment, comprising six consecutive rooms, was reserved for the sole use of the Emperor and his consort should they choose to visit Munich. Such an honour was by no means unlikely; family and marriage ties were strong between the Habsburgs and the Wittelsbachs, and Munich was a convenient stopping-off place for Frankfurt and Augsburg, where imperial coronations were held. In the event the desired visit never occurred during Maximilian’s reign; presumably the war made it impossible.

Blasius Fistulator, now assisted by his sons Wilhelm (b. 1590) and Paul (first doc. 1607), was commissioned to create an imposing set of scagliola doorways with elaborate pediments, in line with the prevailing taste for monumental marble architecture. The background colours of these doorways were made up from combinations of red and grey marbles and granites, inlaid with geometrically shaped polychromatic panels, similar in style to the Reiche Kapelle. Inside the rooms there were scagliola chimney pieces, window surrounds and wall panelling.

A description of the Stone Rooms written in French in 1661 by an unknown visitor reads as follows:

‘the apartment which is destined for the Emperor should he come to Munich, is remarkable, and I do not think that one could see its like, not only in Germany but also in France and Italy. All the doors of the said apartment are made up from different elements and the doorways of a very beautiful marble, enriched with an infinite number of fine and precious stones which form one thousand pretty pictures…’

The Trier Rooms

The Trier Rooms were named after the Saxon elector of Trier, who stayed there for long periods in the eighteenth century. They were originally known as the Royal Rooms (Königlich-Zimmer), and were intended for foreign princes who were passing through Munich.

Although less grand than the Stone Rooms, these too were designed to impress, forming an enfilade that ran the length of the east side of the Emperor’s Courtyard, with a series of closely aligned door surrounds. (The original lay-out for these rooms provided for two separate apartments, one for the dignitary and the other for his consort; a middle room served as a meeting point between the two). The surrounds were all made from a reddish brown scagliola flecked with grey-white veining, imitating a variety of Adnet marble.

Two of these rooms were decorated with richly inlaid scagliola wall panels similar in style to those in the Reich Kapelle. In the 1720s these panels were taken down and reinstated in the new palace of Schleissheim, where they can still be seen today (see Home page). Until the mid-twentieth century they were considered to be the work of Blasius Pfeiffer, but the inscription ‘16WF29’ discovered on the back of one of the panels suggests that they were made in 1629 by his son Wilhelm (see chapter 11).

The Imperial Stairway.

The approach to the Stone Rooms and the Trier Rooms was by way of the Imperial Stairway, finished in the same period (c. 1616). The top of this staircase was flanked on its open side by two pairs of free-standing Tuscan columns set on pedestal bases linked by a balustrade and handrail. The columns and capitals were made in scagliola, the pedestals and balustrade in marble. Opposite, on the closed side of the stair, matching pilasters and pedestals were engaged in the wall, the colours once again of a reddish-brown with off-white veining and large grey streaks. Three monumental stucco figures made by Hans Krumper stood in stucco-decorated wall niches, emphasising the stairway’s imperial connotations: they depicted Otto von Wittelsbach (founder of the dynasty – see above), Emperor Charlemagne and Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian (r. as Holy Roman Emperor 1328-1347).

The Imperial Hall.

At the top of the stairway three scagliola-framed doorways led into the Imperial Hall. On the inside wall of the arched central opening a monumental scagliola structure was formed from fluted pilasters and plain columns set on pedestal bases. These supported a broken pediment with amphorae at the sides and the Wittelsbach coat of arms mounted on an elaborately carved panel in the centre. The background colour was a brownish pink mottled with grey; the columns were black, their lower sections inlaid with Pietre Dure designs. At the far end of the hall a reflecting structure with identical black columns and pediment surrounded the fireplace. A large black niche above the fireplace originally held a porphyry coloured stucco (probably scagliola) statue of Virtue. The four smaller doorways in the Emperor’s Hall were also decorated with scagliola surrounds, as were the mouldings on the walls (cornices, architraves, picture frames etc.).

Like the Stone Rooms, the walls of the Imperial Hall were hung with tapestries designed by Peter Candid and created by Hans van der Biest. They depicted various figures from Antiquity and the Old Testament, who were seen as role models for princely rule.

As its name suggests, the Imperial Hall was one of the grandest rooms in Maximilian’s Residence. The use of scagliola to create monumental architecture recalls the Antiquarium – whose ceremonial function it replaced – and once again underlines its acceptance as a prestigious material.

(The Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room (see below) were remodelled in the early years of the 19th century to provide private apartments for Elector Maximilian IV. It was only during the full-scale reconstruction program after the second world war that the decision was taken to reinstate the original 17th century scheme; this had to be created from historical documents and sources, but without the benefit of photographic records or living memory.)

The Four Greys Room

This room, another 20th century reconstruction, was named after its original ceiling painting which showed Apollo in his chariot being drawn by four white horses; it stands between the far end of the Imperial hall and the Stone Rooms. Its main function was to serve as an antechamber and private dining-room when the Stone Rooms were occupied. Its most important scagliola feature was a pictorial work by Wilhelm Fistulator, which will be discussed in Chapter 12.

The Black Room (c.1610-1620)

Wilhelm V had this room installed in the early 1590s. It stood at the top of a flight of stairs on the upper floor of a new construction built onto the east end of the Antiquarium, where it served as a reception area for various apartments in the old Residence. It also gave access to the ducal library which was situated above the Antiquarium.

Early in the new reign (c. 1600) the room was remodelled and the ceiling raised to create space for an illusionistic architectural painting by the Munich born artist Hans Werl (1570-1609). In the following decade four black scagliola portals were installed, giving the room its name (der Schwarze Saal). They were decorated with sunken panels depicting various marbles, and although the quality of the latter is not of the highest, these jet black portals (imitating Belgian Black marble) are very striking.

A large matching chimney piece made by Wilhelm Fistulator was added in the 1620s. It supported an impressive over-mantel displaying the Wittelsbach coat of arms flanked by two gilded figures, the ensemble probably carved in wood.

Scagliola Perspectives in the Western Grottenhall (pre 1611).

Michaela Liebhardt gives anecdotal evidence of ten scagliola pictorial perspectives on the walls of the western Grotto Hall. The Grottenhalle was a loggia that took up the ground floor of the west range of the Grotto Courtyard, opposite the colonnaded area of the east range that housed the grotto itself.

In the diary entries covering his visit to the Munich Residenz in 1611, Phillip Hainhoffer described the walls of the open-sided hall as being coloured in the style of the Reiche Kapelle and the table in the Antiquarium (made for Prince Wilhelm in the 1590s – see above).

A French visitor, the Baron de Moncorny, recorded that during his visit to the Residence in 1664 the panels in the Garden Hall were covered up to protect them from the weather; and in 1667 the Italian Cardinal Ranuzzio Pallavacino (who studied for a while in Munich alongside Crown Prince Ferdinand-Maria of Bavaria) mentioned the loggias (plural?) covered with perspective scenes (lunghissima veduta).

A palace inventory of ‘Scagliolaarbeiten’ (scagliola works) taken in 1707 recorded the existence of ten Perspectives in the stone garden opposite the coral fountain (i.e. the Grotto fountain). In the same year the Residence’s concierge (Burgpfleger) wrote of the ornate perspectives made from rare marble work in the Sala Terena (Garden Room); a final mention came in 1719 from a Christoph Kalmbach, another visitor to the Residence who was greatly impressed.

In 1730 the facades of the Grotto Courtyard were altered by the Rococo designer Francois de Cuvilliés (1695-1768). The western Grotto Hall was closed in and the scagliola perspectives disappeared. There are no detailed descriptions of their appearance, though there are plenty of other examples of architectural perspectives in scagliola that have survived in the Residence and elsewhere. They are largely the work of Wilhem Fistulator and his workshop, and will be examined in Chapter 12. Liebhardt believed that the 1611 sighting by Hainhoffer implied that Blasius Fistulator was responsible for the work. This seems unlikely on two counts; firstly, there are no other examples of pictorial work by Blasius; and secondly, Hainhoffer’s description likens the work to the Reiche Kapelle as it was in 1611, before the pictorial additions by Wilhelm in the late 1620s. The most likely explanation is that (as in the Reiche Kapelle) Blasius supplied the initial decorative scagliola in the first decade of the century, and his son Wilhelm added the ten perspectives at a later date.

Postscript: Damage and Reconstruction in the Munich Residence.

Almost everything that Blasius Fistulator made for the Munich Residence was subsequently destroyed, and what is seen of his work today is in fact a series of remarkable 20th century reconstructions.

Serious fires between 1674 and 1750 destroyed what was left of Duke Wilhelm’s original Reiche Kapelle (blt. 1585-1590 and subsequently abandoned by his son Maximilian) and, more importantly, the Stone Rooms (blt.1611-1619). The latter were rebuilt in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The Imperial Hall and the Four Greys Room were remodelled in 1779 to create the Court Garden Rooms, a range of neoclassical apartments for Max I Joseph and his wife Karoline von Baden.

Destruction of a different order occurred in April 1944, when the Residence was hit in Munich’s worst bombing raid of the Second World War. The building was gutted by fire, and further bombing and bad weather added to the destruction; stucco and scagliola work suffered particularly badly.

The decision was taken to rebuild, and construction began in 1945 and continued into the twenty-first century. Many of the original interiors were recreated, with meticulous attention paid to records and photographs. Not everything had been lost; at the start of the war all removable art works were stored off-site, including important scagliola pictures and tabletops. By good fortune the wall panelling made for the Trier rooms in the late 1620’s had been moved to the new palace at Schleissheim in the 1720’s, and came through the war unscathed. Six of Wilhelm Fistulator’s pictorial ‘Life of Mary’ panels from the Reiche Kapelle also survived, as did various pieces made as gifts for other destinations (including the Imperial Court in Vienna). Thus there were many original examples to copy, and comparisons between old and new show that this was done with considerable skill and accuracy.

The reconstruction and re-reinstatement of the Munich Residence is a significant event in the history of scagliola, and will be covered in a subsequent chapter.

References:

Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon München: K.G. Saur, 1992- c2011 (supercedes Thieme-Becker).

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.

Michaela Liebhardt, Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987 – Liebhardt catalogues all the scagliola activity at the Munich Residence in the 17th and early 18th centuries making use of surviving court documents, correspondence, inventories and accounts. (The quotes in this chapter are taken from Liebhardt unless otherwise stated).

Dorothea Diemer, Hubert Gerhard und Carlo di Cesare del Palagio Berlin 2004

For Hainhoffer’s circle of contacts, see: Philipp Hainhoffer and Gustavus Adolphus’s Kunstschrank in Uppsala by Hans-Olaf Boström pp. 90-92 in Origins of Museums ed. O.Impey and A Macgregor – Clarendon Press – Oxford 1985. Hainhoffer’s royal and aristocratic contacts were considerable. In addition to a number of German princes, Boström names: King Christian IV of Denmark, Archduke Leopold V of Austria, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (for whom Hainhoffer arranged the making of the Uppsala Künstschrank), the Elector Palatine Frederic V, various Medici Princes, and some travelling English aristocrats, the most distinguished of whom was Thomas Howard, second Earl of Arundel.

Three generations of Wittelsbachs at different ages in their lives: LHS – The future Duke Wilhelm V in 1564 aged 16 (Ambras Castle Innsbruck); RHS – his son, Elector Maximilian I with his son and heir Elector Ferdinand Maria(1636-1679) (Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich)*

This black-and-white photograph taken before the 2nd World War is all that remains of a scagliola table top and carved wooden base dating back to c.1590.*

The Mercury fountain and grotto (reconstructed). In its day it would have been considerably more colourful and dramatic.* (The Grottenhof, Munich Residence).

The Grottenhof Grotto*(detail)

The coat-of-arms of Maximilian I of Bavaria, with the electoral insignia of orb and cross. Detail from a scagliola table top by Wilhelm Pfeiffer c. 1630. The Munich Residence.*

Inlaid scagliola frame (approx. 55 x 45 cms) by Wilhelm Fistulator, second half 1620s (the white marble relief depicts ‘Helle and the Ram’ – click to enlarge). Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich*

Monumental scagliola chimney surround at the north end of the Antiquarium. The square balustrading, also in scagliola, contained the ducal dining area where the ceremonial table with its scagliola top once stood. (Munich Residence c. 1600. This end of the Antiquarium was the least damaged during the 1944 bombing and some of the the scagliola may be original).*

Scagliola dais and stair rails by Blasius Pfeiffer, 1600. Handed panels with inlaid scagliola architectural perspectives by Wilhelm Pfeiffer c. 1630? The Antiquarium, Munich Residence.*

The Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence c. 1607 (reconstructed 2nd half of the 20th century).*

Scagliola panelling on the right-hand side wall of the Reiche Kapelle. Background and geometrically patterned panels by Blasius Fistulator c. 1607, Flower Vases and pictorial panels by Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1630 .*

Detail of scagliola doorway with broken pediment and inlays by Blasius Fistulator. Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence c. 1607 *

Devotional sculpture and reliquary wall cabinets in the Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence (1st half 17th Century?)*

The Stone Rooms (detail): One of a set of tapestries made by the Dutchman Hans van der Biest (early 17th century). The door surround and window reveal are made from scagliola.*

The Stone Rooms (details): scagliola mouldings and internal architecture (orig. 1610-1620; first re-instated 1675-1700; re-instated again 2nd half 20th century. Click on images to enlarge)*

The Trier Rooms: LHS: the enfilade of doorways in matching ‘Adnet’ scagliola. RHS: Closed doorway with scagliola surround. (Original 1610-1620/re-instated 2nd half 20th century. Click on images to enlarge)*

The Imperial Stairway with scagliola columns and pilasters. The statues are by Hans Krumper. (original 1610-1616/re-instated 2nd half 20th century).*

The Imperial Hall: View through the scagliola central doorway towards the top of the Imperial Stairway (blt. 1612-1616: replaced 1799: re-instated 2nd half 20th century)*

The Imperial Hall: LHS view towards the fireplace and doorway into the Four Greys Room. RHS Scagliola column detail with inlays. (Click on images to enlarge)*

The Four Greys Room, named after a former ceiling painting of Apollo in his chariot (blt. 1612-1616: replaced 1799: re-instated 2nd half 20th century)*

The Black Room: LHS two of the four black scagliola door portals; RHS upper section and pediment with inlaid panels (blt. and restructured 1590s-1620, re-instated 2nd half 20th Century. Click on images to enlarge)*

A scagliola architectural perspective of the type that would have decorated the Western Grottenhall of the Munich Residence. Similar in style to Wilhelm Fistulator’s pictorial work, it is less sophisticated than his earlier ‘Life of Mary’ sequence in the Reiche Kapelle, and may have been a workshop piece. (Bavarian National museum, Munich c. 1640)*

Detail from panel*

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze,