The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

To understand the religious scagliola of the period requires an awareness of the role played by its symbolism. The various components that went to make up an altar front were not merely decorative; they expressed meanings that were clearly readable to congregations of the time, and every bit as important as any aesthetic value. Post-reformation Catholics felt that knowledge of this symbolic language was something that set them apart from Protestants and unbelievers. In the Catholic art of the period, each colour, flower and insect has its own significance, each precious stone has its function, and even the shape of the design tells a story.

Many books have been written about Christian symbolism down the years, with many conflicting interpretations. To further complicate things, the meaning of symbols was not finite and could change depending on the context in which they appeared. The following selection illustrates some of the symbols that appear most frequently in scagliola altar fronts; the meanings given should be taken as illustrative rather than definitive.

Flowers

• Rose: when white, the symbol of the Virgin and purity; when red, the symbol of the Passion and martyrdom, from its thorns and blood-red colour. Also an important symbol of the Rosary of the Madonna.

LHS – an oval band of white roses and tulips framing the Madonna of the Rosary (attrib. Giovan Marco Barzelli, c. 1680-90. Church of San Giuseppe Calasanzio, Corregio).

RHS – two red roses on thorny stems above a central cartouche containing grapes and corn, which represent the bread and wine of Holy Communion (Attrib. Giovan Battista Rapa, 1703. Plebeian Church of San Stefano, Castiglione d’Intelvi).

(Click on images to enlarge.)

• Carnation: reputed to have grown from the tears of the grieving Mary at the foot of the cross. Usually shown as the red variety, which grows wild.

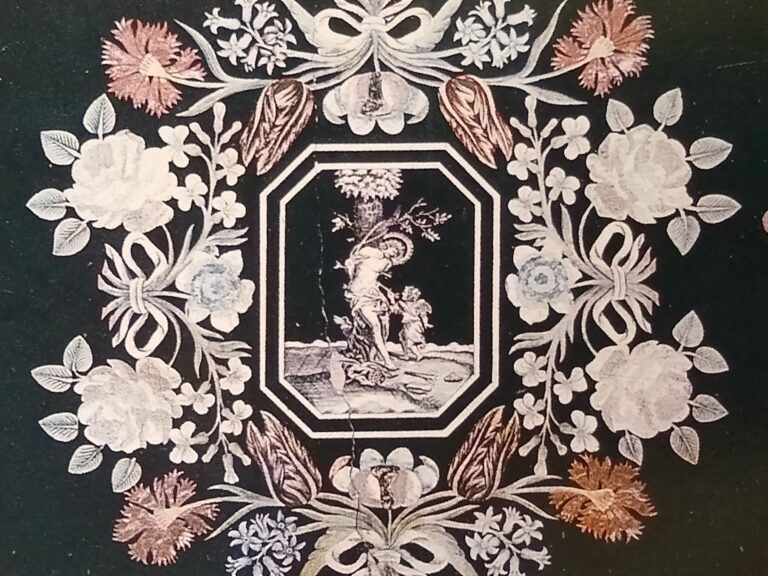

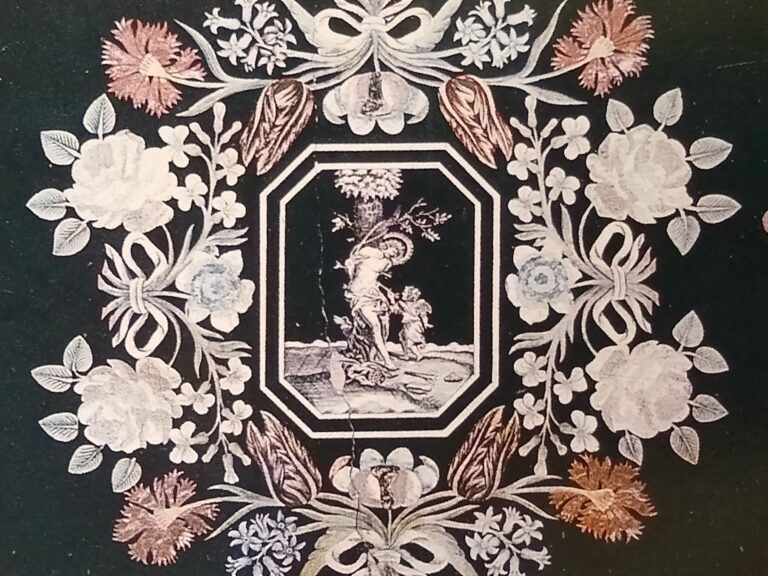

A floral wreath of red carnations and white roses – symbols of martyrdom and purity – surrounding an image of St. Sebastian pierced with arrows (signed and dated Giovan Marco Barzelli 1685. Church of San Giorgio, Reggio Emilia).

• Lilly of the Valley: a symbol of Advent and Christ’s incarnation, because their early flowering signals the arrival of spring; also humility and the purity of the Virgin, because its flowers are often turned to the ground.

Paliotto in the Santuario della Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi. Como. Two sprays of white Lilly of the Valley can be seen on either side of the Madonna robed in carmine (Att. Domenico Solari di Francesco di Verna, first half 1700s).

• Tulip: interpreted as a symbol of the love of God and the Holy Spirit, because it dies without the light of the sun.

Paliotto in the Chiesa della Madonna del’Olivo, Maciano di Pennabili, showing red tulips around the image of San Pasquale Baylón (attr. ‘Maestro dei Francescani’, dated 1753)

• A vase of flowers: a symbol of spiritual perfection, alternatively a memento mori warning of the transitory nature of life.

Flower vases by Giovanni Gavignani (LHS – altar of St. Anthony of Padua, Church of San Nicolò, Carpi, signed and dated 1652) and Giovan Marco Barzelli (RHS – altar of the Madonna della Misericordia, Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena, signed and dated 1683).

Birds and Insects

• Goldfinch: a symbol of Christ because it was described (in the Apocrypha) as a playmate of the baby Jesus, also because it collected a drop of Christ’s blood at the crucifixion, from which it got its red mask.

Scagliola goldfinch in the parish church of SS Nazario e Celso, Blessagno. Como (dated 1743).

• Dove: symbolises the Holy Ghost in the Trinity; also a symbol of peace and concord from its role in the story of Noah’s Ark.

Scagliola dove in the church of Maria degli Angeli, Lugano.

Scagliola dove in the church of Maria degli Angeli, Lugano.

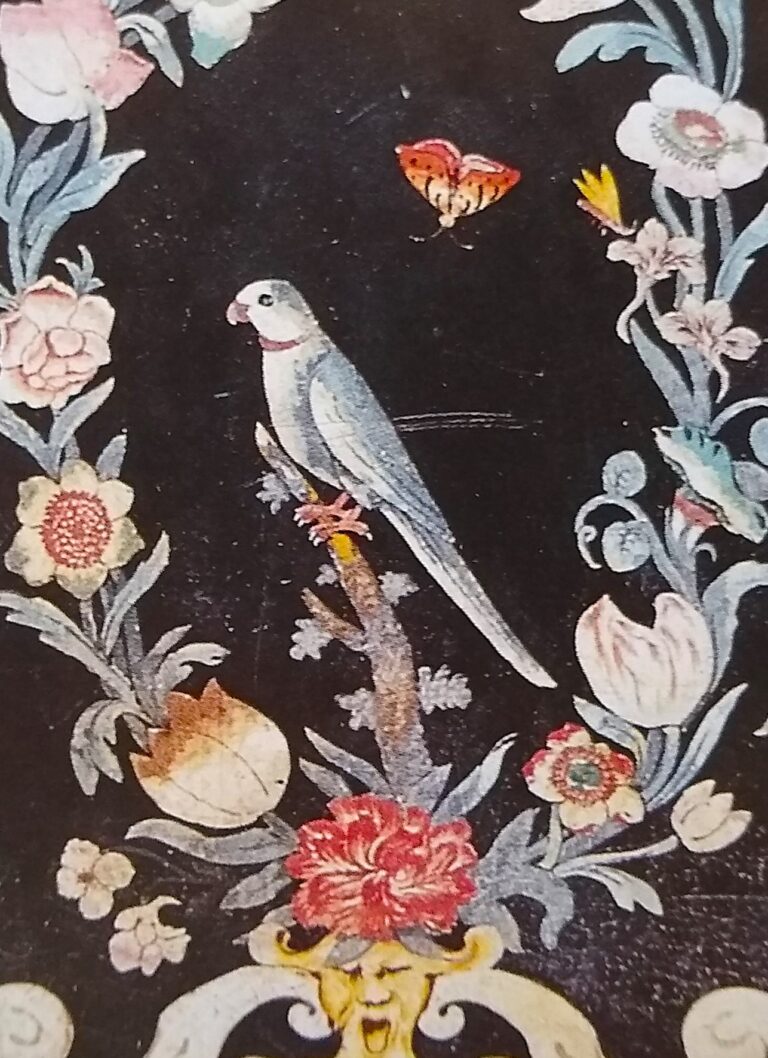

• Parrot: refers, through its ability to speak, to the Word of God; also to Mary, because it appears to say ‘Ave’, repeating the Angel’s greeting to Mary at the Annunciation. Several birds feeding off fruit or nectar refer to the receiving of the Holy Sacrament during Mass. (Sometimes the ‘celebrants’ are distinguished from the congregation by their opened wings).

Paired scagliola parrots feeding from a vase of flowers in the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi, Como,

• Butterfly: its transformation from a chrysalis symbolises the resurrection and the immortality of the soul; it can also appear as a memento mori.

One of a pair of handed panels showing a butterfly circling a dove in a paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary of Fontanellato, Parma (signed and dated 1701)

Objects

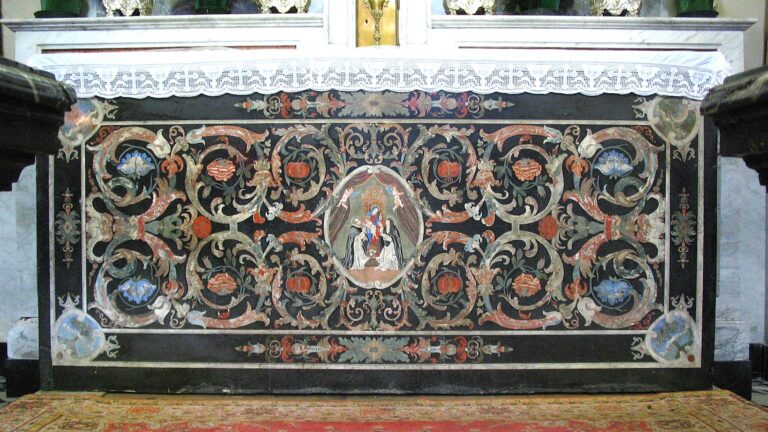

• Volutes: a symbol of Sacred and Eternal Truth, as seen in the swirling patterns formed by the heavenly stars. Analogous with the spiritual labyrinth of the Middle Ages, it represents the spiritual search for God, but also the presence of the divine. When volutes appear in pairs, as architectural supports or symmetrical scrolling foliage, they recall the Old and the New Testament; three volutes in a vine stem or branch of foliage refer to the Trinity, and four confirm the presence of a holy place.

Scagliola altar in the church of San Stefano, Gottro, Como, showing a nativity scene set within four symmetrical vine stems, each with three volutes. The numerical relationship of 3:4 has religious significance. (late 17th/early 18th C.?)

• Precious Stones: in the Revelation of St. John, the Celestial City is described as having walls built of precious stones: Jasper, Sapphire, Chalcedony, Emerald, Sardonyx etc. The altar, with its square sides and ‘jewel encrusted’ faces, can be seen as an analogy for the New Jerusalem.

Tri-partite scagliola altar front in the church of San Vittore, Porlezza, Como. The three figurative panels are surrounded by black borders inlaid with geometrically shaped precious stones, reminiscent of classical pietra dura work (c. 1750?)

• Ribbon/Strapwork: symbolises the journey through life for the faithful, in which birds and flowers – symbols of good works or spiritual grace – are often encountered along the way.

Central section of a scagliola altar piece with ribbon work in which flowers and birds appear at regular intervals. The central image depicts St. Francis receiving the stigmata. (Carpi Museum, late 1600s).

Colours

• White: purity, holiness and virtue

• Blue: Heavenly grace, therefore often Mary, but also the coming of Christ.

• Red: the Holy Spirit and the presence of God; also the blood of Christ and the martyrs.

• Gold: a symbol of what is precious and valuable, therefore the presence of God.

• Green: refers to living things and the promise of new life.

• Yellow: renewal and hope.

• Brown: the earth, poverty and humility.

• Black: death and fear, but also authority and power.

Top row left to right:

1. Crucifixion by Ludovico Leoni (Church of San Sepulcro – 1st quarter 1700s). 2. Immaculate Conception by Maestro dei Francescani (Church of the Madonna of the Olives Maciano di Pennabili, – d.1753) 3. A sainted bishop flanked by red drapery, a symbol of impending martyrdom, by Giovanni Massa (Oratorio della Concezione, Guastalla, Reg. Em. c. 1720-40) 4. Golden acanthus leaves by Nicola Flamini (Collegiata of Sant’Agatha Feltria, Pesaro – c. 1700).

Bottom row left to right: 5. Central panel depicting Saints Peter, Paul and King Louis IX of France within a green laurel leaf mandorla, by Domenico Pianon (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – last quarter of 1700s). 6. Central panel of Mary Magdalene by unknown Modenese scagliolist (Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena- end 1600s). 7. St. Anthony Abbot with his pig by Maestro dell’Arte Gargiolari (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – d.1670). 8. Detail of swirling foliage that seems to be suspended in black space by Giovanni Pozzuoli (Carpi Cathedral – c. 1730s).

***

In addition to the examples given above, there is a vast iconography surrounding the Holy Family and the saints, many of whom appear in the previous chapters. Different objects and images refer to key events, of which the most represented is the Crucifixion itself. The saints have their own objects of martyrdom to identify them – for example the arrow for St. Sebastian, the wheel for St. Catherine – or depictions of well-known moments from their lives. St. Anthony of Padua, who cared for animals, is often shown with his pig, St. Paul falls from his horse. The life of Mary, which gained considerable significance during the Counter Reformation, is particularly rich in such images – the Annunciation, the Immaculate Conception, the Nativity etc. These icons and well-known scenes were used by the scagliolists to link their altar fronts with the saint or religious event to which the altar and chapel were dedicated

References: For Flowers, Birds and Insects, I am indebted to Silvia Angelini who made available her graduation thesis: Diffusione dei paliotti in scagliola nella Valmarecchia. Università degli Studi di Urbino “Carlo Bo”, Facoltà di lettere e filosofia: 2004-5. Pp 33-40

For Objects and Colours see: Floriana Spalla, Imitazione e Belleza – Opere e tecniche dell’arredo sacro in scagliola, 2003 Ente di Gestione della Riserva Naturale Speciale del Sacro Monte della SS. Trinità di Ghiffa.

Also: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

To understand the religious scagliola of the period requires an awareness of the role played by its symbolism. The various components that went to make up an altar front were not merely decorative; they expressed meanings that were clearly readable to congregations of the time, and every bit as important as any aesthetic value. Post-reformation Catholics felt that knowledge of this symbolic language was something that set them apart from Protestants and unbelievers. In the Catholic art of the period, each colour, flower and insect has its own significance, each precious stone has its function, and even the shape of the design tells a story.

Many books have been written about Christian symbolism down the years, with many conflicting interpretations. To further complicate things, the meaning of symbols was not finite and could change depending on the context in which they appeared. The following selection illustrates some of the symbols that appear most frequently in scagliola altar fronts; the meanings given should be taken as illustrative rather than definitive.

Flowers

• Rose: when white, the symbol of the Virgin and purity; when red, the symbol of the Passion and martyrdom, from its thorns and blood-red colour. Also an important symbol of the Rosary of the Madonna.

LHS – an oval band of white roses and tulips framing the Madonna of the Rosary (attrib. Giovan Marco Barzelli, c. 1680-90. Church of San Giuseppe Calasanzio, Corregio).

RHS – two red roses on thorny stems above a central cartouche containing grapes and corn, which represent the bread and wine of Holy Communion (Attrib. Giovan Battista Rapa, 1703. Plebeian Church of San Stefano, Castiglione d’Intelvi).

(Click on images to enlarge.)

Above – an oval band of white roses and tulips framing the Madonna of the Rosary (attrib. Giovan Marco Barzelli, c. 1680-90. Church of San Giuseppe Calasanzio, Corregio).

Below – two red roses on thorny stems above a central cartouche containing grapes and corn, which represent the bread and wine of Holy Communion (Attrib. Giovan Battista Rapa, 1703. Plebeian Church of San Stefano, Castiglione d’Intelvi).

(Click on images to enlarge.)

• Carnation: reputed to have grown from the tears of the grieving Mary at the foot of the cross. Usually shown as the red variety, which grows wild.

A floral wreath of red carnations and white roses – symbols of martyrdom and purity – surrounding an image of St. Sebastian pierced with arrows (signed and dated Giovan Marco Barzelli 1685. Church of San Giorgio, Reggio Emilia).

A floral wreath of red carnations and white roses – symbols of martyrdom and purity – surrounding an image of St. Sebastian pierced with arrows (signed and dated Giovan Marco Barzelli 1685. Church of San Giorgio, Reggio Emilia).

• Lilly of the Valley: a symbol of Advent and Christ’s incarnation, because their early flowering signals the arrival of spring; also humility and the purity of the Virgin, because its flowers are turned to the ground.

Paliotto in the Santuario della Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi. Como. Two sprays of white Lilly of the Valley can be seen on either side of the Madonna robed in carmine (Att. Domenico Solari di Francesco di Verna, first half 1700s).

Paliotto in the Santuario della Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi. Como. Two sprays of white Lilly of the Valley can be seen on either side of the Madonna robed in carmine (Att. Domenico Solari di Francesco di Verna, first half 1700s).

• Tulip: interpreted as a symbol of the love of God and the Holy Spirit, because it dies without the light of the sun.

Paliotto in the Chiesa della Madonna del’Olivo, Maciano di Pennabili, showing red tulips around the image of San Pasquale Baylón (attr. ‘Maestro dei Francescani’, dated 1753).

Paliotto in the Chiesa della Madonna del’Olivo, Maciano di Pennabili, showing red tulips around the image of San Pasquale Baylón (attr. ‘Maestro dei Francescani’, dated 1753).

• A vase of flowers: a symbol of spiritual perfection, alternatively a memento mori warning of the transitory nature of life.

Flower vases by Giovanni Gavignani (LHS – altar of St. Anthony of Padua, Church of San Nicolò, Carpi, signed and dated 1652) and Giovan Marco Barzelli (RHS – altar of the Madonna della Misericordia, Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena, signed and dated 1683).

Flower vases by Giovanni Gavignani (Above – altar of St. Anthony of Padua, Church of San Nicolò, Carpi, signed and dated 1652) and Giovan Marco Barzelli (Below – altar of the Madonna della Misericordia, Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena, signed and dated 1683).

Birds and Insects

• Goldfinch: a symbol of Christ because it was described (in the Apocrypha) as a playmate of the baby Jesus, also because it collected a drop of Christ’s blood at the crucifixion, from which it got its red mask.

Scagliola goldfinch in the parish church of SS Nazario e Celso, Blessagno. Como (dated 1743).

Scagliola goldfinch in the parish church of SS Nazario e Celso, Blessagno. Como (dated 1743).

• Dove: symbolises the Holy Ghost in the Trinity; also a symbol of peace and concord from its role in the story of Noah’s Ark.

Scagliola dove in the church of Maria degli Angeli, Lugano.

Scagliola dove in the church of Maria degli Angeli, Lugano.

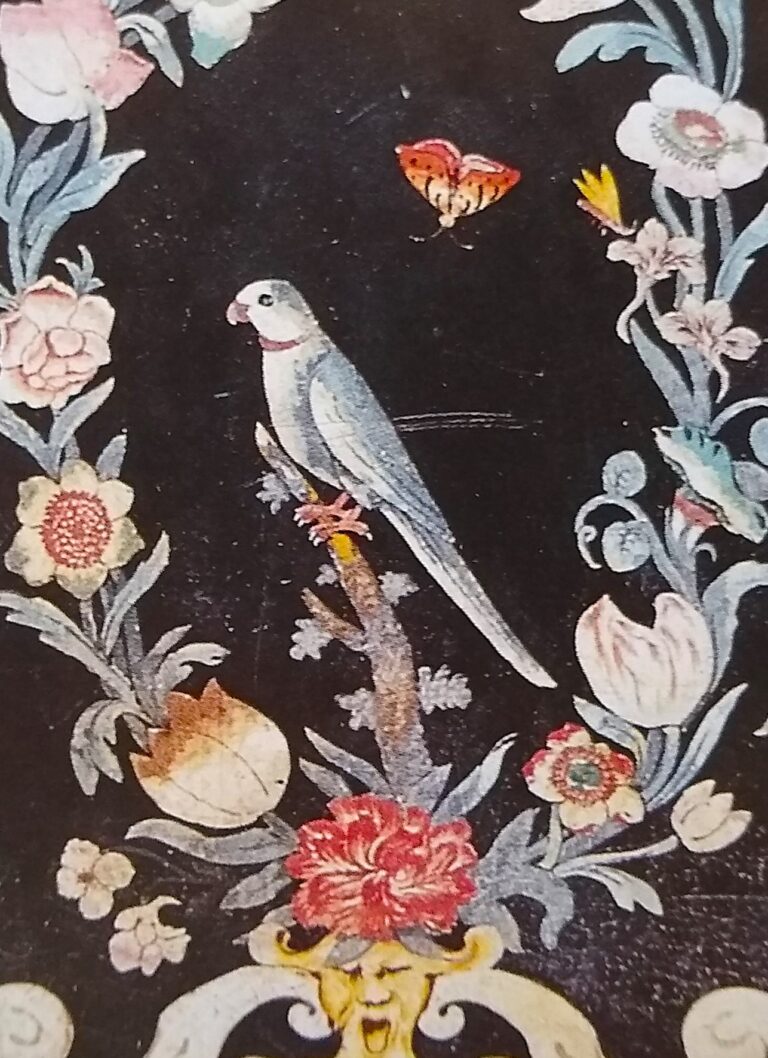

• Parrot: refers, through its ability to speak, to the Word of God; also to Mary, because it appears to say ‘Ave’, repeating the Angel’s greeting to Mary at the Annunciation. Several birds feeding off fruit or nectar refer to the receiving of the Holy Sacrament during Mass. (Sometimes the ‘celebrants’ are distinguished from the congregation by their opened wings).

Paired scagliola parrots feeding from a vase of flowers in the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi, Como,

Paired scagliola parrots feeding from a vase of flowers in the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Carmine, Casasco d’Intelvi, Como,

• Butterfly: its transformation from a chrysalis symbolises the resurrection and the immortality of the soul; it can also appear as a memento mori.

One of a pair of handed panels showing a butterfly circling a dove in a paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary of Fontanellato, Parma (signed and dated 1701)

One of a pair of handed panels showing a butterfly circling a dove in a paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary of Fontanellato, Parma (signed and dated 1701)

Objects

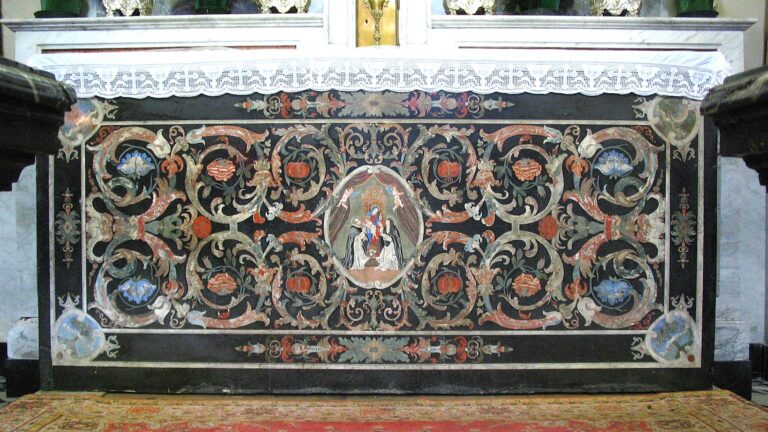

• Volutes: a symbol of Sacred and Eternal Truth, as seen in the swirling patterns formed by the heavenly stars. Analogous with the spiritual labyrinth of the Middle Ages, it represents the spiritual search for God, but also the presence of the divine. When volutes appear in pairs, as architectural supports or symmetrical scrolling foliage, they recall the Old and the New Testament; three volutes in a vine stem or branch of foliage refer to the Trinity, and four confirm the presence of a holy place.

Scagliola altar in the church of San Stefano, Gottro, Como, showing a nativity scene set within four symmetrical vine stems, each with three volutes. The numerical relationship of 3:4 has religious significance, (late 17th/early 18th C.?)

• Precious Stones: in the Revelation of St. John, the Celestial City is described as having walls built of precious stones: Jasper, Sapphire, Chalcedony, Emerald, Sardonyx etc. The altar, with its square sides and ‘jewel encrusted’ faces, can be seen as an analogy for the New Jerusalem.

Tri-partite scagliola altar front in the church of San Vittore, Porlezza, Como. The three figurative panels are surrounded by black borders inlaid with geometrically shaped precious stones, reminiscent of classical pietra dura work (c. 1750?)

• Ribbon: symbolises the journey through life for the faithful, in which there are often bunches of flowers – symbols of good works or spiritual grace – along the way.

Central section of a scagliola altar piece with ribbon work in which flowers and birds appear at regular intervals. The central image depicts St. Francis receiving the stigmata. (Carpi Museum, late 1600s).

Colours

• White: purity, holiness and virtue

• Blue: Heavenly grace, therefore often Mary, but also the coming of Christ.

• Red: the Holy Spirit and the presence of God; also the blood of Christ and the martyrs.

• Gold: a symbol of what is precious and valuable, therefore the presence of God.

• Green: refers to living things and the promise of new life.

• Yellow: renewal and hope.

• Brown: the earth, poverty and humility.

• Black: death and fear, but also authority and power..

Top row left to right: 1. Crucifixion by Ludovico Leoni (Church of San Sepulcro – 1st quarter 1700s). 2. Immaculate Conception by Maestro dei Francescani (Church of the Madonna of the Olives Maciano di Pennabili, – d.1753) 3. A sainted bishop flanked by red drapery, a symbol of impending martyrdom, by Giovanni Massa (Oratorio della Concezione, Guastalla, Reg. Em. c. 1720-40) 4. Golden acanthus leaves by Nicola Flamini (Collegiata of Sant’Agatha Feltria, Pesaro – c. 1700).

Bottom row left to right: 5. Central panel depicting Saints Peter, Paul and King Louis IX of France within a green laurel leaf mandorla, by Domenico Pianon (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – last quarter of 1700s). 6. Central panel of Mary Magdalene by unknown Modenese scagliolist (Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena- end 1600s). 7. St. Anthony Abbot with his pig by Maestro dell’Arte Gargiolari (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – d.1670). 8. Detail of swirling foliage that seems to be suspended in black space by Giovanni Pozzuoli (Carpi Cathedral – c. 1730s).

Top to bottom: 1. Crucifixion by Ludovico Leoni (Church of San Sepulcro – 1st quarter 1700s). 2. Immaculate Conception by Maestro dei Francescani (Church of the Madonna of the Olives Maciano di Pennabili, – d.1753) 3. A sainted bishop flanked by red drapery, a symbol of impending martyrdom, by Giovanni Massa (Oratorio della Concezione, Guastalla, Reg. Em. c. 1720-40) 4. Golden acanthus leaves by Nicola Flamini (Collegiata of Sant’Agatha Feltria, Pesaro – c. 1700). 5. Central panel depicting Saints Peter, Paul and King Louis IX of France within a green laurel leaf mandorla, by Domenico Pianon (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – last quarter of 1700s). 6. Central panel of Mary Magdalene by unknown Modenese scagliolist (Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena- end 1600s). 7. St. Anthony Abbot with his pig by Maestro dell’Arte Gargiolari (Church of San Giaccomo Maggiore, Bologna – d.1670). 8. Detail of swirling foliage that seems to be suspended in black space by Giovanni Pozzuoli (Carpi Cathedral – c. 1730s).

***

In addition to the above, there is a vast iconography surrounding the Holy Family and the saints. Different objects and images refer to key events, of which the most represented is the Crucifixion itself. The saints have their own objects of martyrdom to identify them – for example the arrow for St. Sebastian, the wheel for St. Catherine – or depictions of well-known moments from their lives – St. Anthony of Padua is shown with the infant Christ in his arms, St. Paul falls from his horse. The life of Mary, which gained considerable significance during the Counter Reformation, is particularly rich in such images – the Annunciation, the Immaculate Conception, the Nativity etc. These icons and well-known scenes were used by the scagliolists to link their altar fronts with the saint or religious event to which the altar and chapel were dedicated.

References: For Flowers, Birds and Insects, I am indebted to Silvia Angelini who made available her graduation thesis: Diffusione dei paliotti in scagliola nella Valmarecchia. Università degli Studi di Urbino “Carlo Bo”, Facoltà di lettere e filosofia: 2004-5. Pp 33-40

For Objects and Colours see: Floriana Spalla, Imitazione e Belleza – Opere e tecniche dell’arredo sacro in scagliola, 2003 Ente di Gestione della Riserva Naturale Speciale del Sacro Monte della SS. Trinità di Ghiffa.

Also: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.