Chapter 2: The Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages (conventionally seen as the period from the fall of Rome in 476 AD until the mid-fifteenth century), marble played a minor role in the decoration of secular interiors. Coloured marble artefacts from the classical period were highly prized for their rarity and antiquity, but the knowledge and skills required to produce them had been lost.

Christendom’s rulers were itinerant for much of the period, moving between castles and well-defended manor complexes with their armed retainers, their retinues and their portable households; even in times of peace, status and military power had to be seen to be believed. In this context a building’s security and functionality (the ability to protect, house and feed, dispense justice etc.) took precedence over expensive furnishings, especially if the latter were not portable.

The walls of the wealthy were covered with a combination of expensive fabrics and tapestries, timber wainscoting, and frescoes. Tapestries were time-consuming and hugely expensive to make, but they could travel with their owners and be shown off, or stored away for safe-keeping; wainscoting was a practical solution to insulating stone walls from the cold and damp, and it could be decorated with carving, gold leaf and paint; frescoes were quick and cheap to produce and, like tapestries, told stories of religious, historical or everyday events that had significance to their owners; they were not considered valuable and could be plastered over and replaced. Floors were generally made from stone, terracotta or timber. Ceilings were made from timber (often painted and/or decorated with carved, sometimes gilt ornament); or they were lime-plastered and painted.

In the case of religious buildings, stone and wood-carving reached high degrees of sophistication in the medieval period, as did fresco painting. This can be seen in the remarkable Romanesque and Gothic churches and cathedrals that have survived all over Europe. Vaulting for these enormous buildings was formed from timber or stone and brick. In special cases ceilings and apses were faced with costly Byzantine mosaics.

Such buildings were more likely than their secular counterparts to include white or coloured marble furnishings, and in particular columns. These were not made to measure, but obtained piecemeal from Ancient Roman sites; when used in colonnades, their differing heights and diameters were compensated for with assorted column bases and capitals, themselves often of Roman origin.

Charlemagne, at the end of the eighth century, ordered ancient porphyry and granite columns from Ravenna and Rome to be carried across the Alps and installed in his chapel in Aachen; such columns had never been seen so far north and they were greatly admired, not only for their appearance, but for their associations with the imperial past. The connection would have had great significance for Europe’s first Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-813 AD).

Areas near large deposits of marble, such as the Veneto region in north eastern Italy, with its distinctive red and yellow Veronese marbles (Rosso and Giallo di Verona), and Tuscany, with its proximity to the grey-white marble in the Apuan Alps above Carrara, (known to the Romans as Luna marble), used their local resources as building materials, just as the Romans had done before them.

In Florence the outside of the Baptistery (begun c.1059) was clad in white Carrara marble inlaid with bands and panels of green Serpentine from nearby Prato. Both stones were sourced regionally, and many of Tuscany’s churches were faced with this two-toned arrangement of white and dark green.

At the end of the eleventh century, original inlaid marble work began to re-appear in Italy, still in a predominantly religious context. Credit for this is given to the Cosmati family, sculptors and architects from Rome, who took as their original model the inlaid floor at the abbey of Monte Cassino, created by Byzantine craftsmen in 1066.

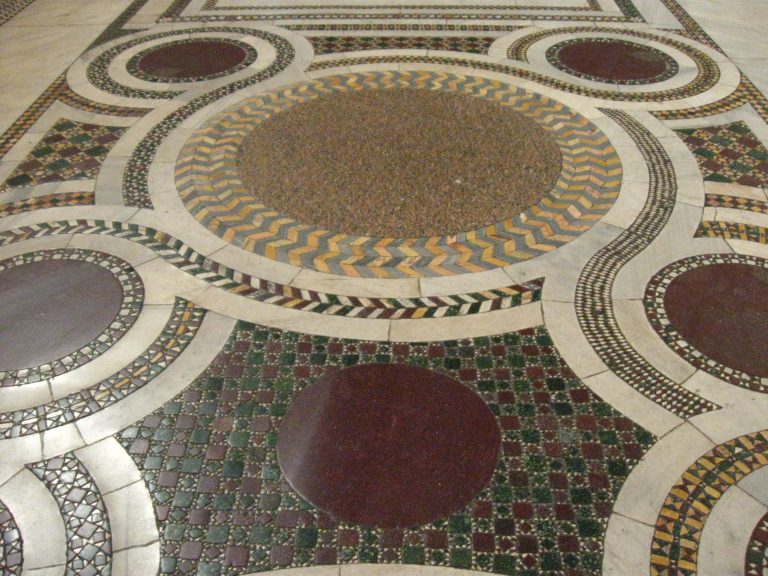

The work consisted of small geometrically shaped pieces of polished stone, mainly porphyry and green serpentine, mixed with coloured glass and gilt ceramic, and inlaid in wide interweaving bands set into a grey/white marble background. The bands often enclosed larger panels of coloured marble and hardstone. The materials were salvaged from the Roman ruins under papal license. (The enormous deposits of ancient marble and hard-stone buried beneath medieval Rome in buildings such as Nero’s Domus Aurea did not come to light until the end of the fifteenth century – see Chapter 3. The fragments needed to produce Cosmati pavements presumably came from sites above or close to the city’s medieval surface.)

Roman ‘Cosmatesque’ floors and panelled surfaces were produced from the early twelfth century until the early fourteenth, when the papacy moved to Avignon and patronage declined. Similarly styled work can be seen in churches throughout central and southern Italy. The Cosmati technique travelled as far as London, where Roman craftsmen installed the famous Cosmati Pavement in Westminster Abbey, commissioned in 1268 by King Henry III.

In the cathedral of Siena, the enormous marble floor, begun in the last quarter of the 1300s, was initially restricted to three colours, red, black and white. In the following century yellow, brown, pink and grey marbles were added, to accommodate the complexity of the designs, which, in a break from contemporary Roman and Florentine marble work, portrayed figures and narrative events in a pictorial style.

By the end of the fifteenth century, coloured marble was in regular use for religious furnishings: altars, fonts, pulpits, memorial stones and funerary monuments. As a result of this activity, the Roman and Florentine workshops were able to develop their skills and experience, at the same time attracting craftsmen from other centres of expertise such as Milan and Paris.

References: Wolfram Koeppe, Mysterious and Prized: Hardstones in Human History before the Renaissance in Art of the Royal Court, Treasures in Pietre dure from the Palaces of Europe ed.Wolfram Koeppe, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2008 pp.9-10.

Annamaria Giusti, L’Arte delle Pietre Dure: da Firenze all’Europa Florence 2005 p.18

Detail of wall fresco from La Chambre du Cerf (Room of the Stag), Papal Palace, Avignon. The frescoes were painted by Italian or French artists in the mid-1300s, and depict secular scenes of hunting and fishing.

12th. C. Byzantine Mosaics in the central apse of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome. The church was re-built in the same century using marble from the antique Baths of Caracalla.

Assorted marble columns, bases and capitals in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome. A Christian church already stood on the site in 574 AD. It was restored and enlarged to its present dimensions by the Franciscans in the 13th C.

Examples of important medieval churches built with locally-sourced marble. (Click on photos to enlarge). LHS – Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence, (blt. 1059-1128) using white marble from Carara and green Serpentine marble from Prato. RHS – Basilica of Sant’Anastasia, Verona (blt. 1290-1400) with its distinctive Rosso di Verona columns and assorted floor tiles from the nearby quarries at Vlapollicella. (Similar materials were used to build Verona’s Roman Arena, built c. AD 30)

Detail of Cosmati Floor in the Basilica Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. (13th Century)

The Story of David, one of the pictorial inlaid marble panels in the floor of Siena Cathedral, Tuscany (early 15th C.)

Chapter 2: The Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages (conventionally seen as the period from the fall of Rome in 476 AD until the mid-fifteenth century), marble played a minor role in the decoration of secular interiors. Coloured marble artefacts from the classical period were highly prized for their rarity and antiquity, but the knowledge and skills required to produce them had been lost.

Christendom’s rulers were itinerant for much of the period, moving between castles and well-defended manor complexes with their armed retainers, their retinues and their portable households; even in times of peace, status and military power had to be seen to be believed. In this context a building’s security and functionality (the ability to protect, house and feed, dispense justice etc.) took precedence over expensive furnishings, especially if the latter were not portable.

Detail of wall fresco from La Chambre du Cerf (Room of the Stag), Papal Palace, Avignon. The frescoes were painted by Italian or French artists in the mid-1300s, and depict secular scenes of hunting and fishing.

The walls of the wealthy were covered with a combination of expensive fabrics and tapestries, timber wainscoting, and frescoes. Tapestries were time-consuming and hugely expensive to make, but they could travel with their owners and be shown off, or stored away for safe-keeping; wainscoting was a practical solution to insulating stone walls from the cold and damp, and it could be decorated with carving, gold leaf and paint; frescoes were quick and cheap to produce and, like tapestries, told stories of religious, historical or everyday events that had significance to their owners; they were not considered valuable and could be plastered over and replaced. Floors were generally made from stone, terracotta or timber. Ceilings were made from timber (often painted and/or decorated with carved, sometimes gilt ornament); or they were lime-plastered and painted.

In the case of religious buildings, stone and wood-carving reached high degrees of sophistication in the medieval period, as did fresco painting. This can be seen in the remarkable Romanesque and Gothic churches and cathedrals that have survived all over Europe. Vaulting for these enormous buildings was formed from timber or stone and brick. In special cases ceilings and apses were faced with costly Byzantine mosaics.

12th. C. Byzantine Mosaics in the central apse of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome. The church was re-built in the same century using marble from the antique Baths of Caracalla.

Such buildings were more likely than their secular counterparts to include white or coloured marble furnishings, and in particular columns. These were not made to measure, but obtained piecemeal from Ancient Roman sites; when used in colonnades, their differing heights and diameters were compensated for with assorted column bases and capitals, themselves often of Roman origin.

Assorted marble columns, bases and capitals in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome. A Christian church already stood on the site in 574 AD. It was restored and enlarged to its present dimensions by the Franciscans in the 13th C.

Charlemagne, at the end of the eighth century, ordered ancient porphyry and granite columns from Ravenna and Rome to be carried across the Alps and installed in his chapel in Aachen; such columns had never been seen so far north and they were greatly admired, not only for their appearance, but for their associations with the imperial past. The connection would have had great significance for Europe’s first Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-813 AD).

Areas near large deposits of marble, such as the Veneto region in north eastern Italy, with its distinctive red and yellow Veronese marbles (Rosso and Giallo di Verona), and Tuscany, with its proximity to the grey-white marble in the Apuan Alps above Carrara, (known to the Romans as Luna marble), used their local resources as building materials, just as the Romans had done before them.

Basilica of Sant’Anastasia, Verona (blt. 1290-1400) with its distinctive Rosso di Verona columns and assorted floor tiles from the nearby quarries at Valpollicella. (Similar materials were used to build Verona’s Roman Arena, built c. AD 30).

In Florence the outside of the Baptistery (begun c.1059) was clad in white Carrara marble inlaid with bands and panels of green Serpentine from nearby Prato. Both stones were sourced regionally, and many of Tuscany’s churches were faced with this two-toned arrangement of white and dark green.S

Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence, (blt. 1059-1128) using white marble from Carara and green Serpentine marble from Prato.

At the end of the eleventh century, original inlaid marble work began to re-appear in Italy, still in a predominantly religious context. Credit for this is given to the Cosmati family, sculptors and architects from Rome, who took as their original model the inlaid floor at the abbey of Monte Cassino, created by Byzantine craftsmen in 1066. The work consisted of small geometrically shaped pieces of polished stone, mainly porphyry and green serpentine, mixed with coloured glass and gilt ceramic, and inlaid in wide interweaving bands set into a grey/white marble background. The bands often enclosed larger panels of coloured marble and hardstone. The materials were salvaged from the Roman ruins under papal license. (The enormous deposits of ancient marble and hard-stone buried beneath medieval Rome in buildings such as Nero’s Domus Aurea did not come to light until the end of the fifteenth century – see Chapter 3. The fragments needed to produce Cosmati pavements presumably came from sites above or close to the city’s medieval surface.)

Detail of Cosmati Floor in the Basilica Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. (13th Century)

Roman ‘Cosmatesque’ floors and panelled surfaces were produced from the early twelfth century until the early fourteenth, when the papacy moved to Avignon and patronage declined. Similarly styled work can be seen in churches throughout central and southern Italy. The Cosmati technique travelled as far as London, where Roman craftsmen installed the famous Cosmati Pavement in Westminster Abbey, commissioned in 1268 by King Henry III.

In the cathedral of Siena, the enormous marble floor, begun in the last quarter of the 1300s, was initially restricted to three colours, red, black and white. In the following century yellow, brown, pink and grey marbles were added, to accommodate the complexity of the designs, which, in a break from contemporary Roman and Florentine marble work, portrayed figures and narrative events in a pictorial style.

The Story of David, one of the pictorial inlaid marble panels in the floor of Siena Cathedral, Tuscany (early 15th C.)

By the end of the fifteenth century, coloured marble was in regular use for religious furnishings: altars, fonts, pulpits, memorial stones and funerary monuments. As a result of this activity, the Roman and Florentine workshops were able to develop their skills and experience, at the same time attracting craftsmen from other centres of expertise such as Milan and Paris.

References: Wolfram Koeppe, Mysterious and Prized: Hardstones in Human History before the Renaissance in Art of the Royal Court, Treasures in Pietre dure from the Palaces of Europe ed.Wolfram Koeppe, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2008 pp.9-10.

Annamaria Giusti, L’Arte delle Pietre Dure: da Firenze all’Europa Florence 2005 p.18