3. The origin of the word 'Scagliola', its use and other terms.

The Italian word scagliola (pronounced with a silent ‘g’), was in use in the Middle Ages long before the arrival of artificial marble. ‘Scagliaiuola’ was the name given in parts of central Italy to the mineral rock from which gypsum plaster (the basic ingredient of Plaster of Paris) was obtained. Only later did it become associated with the production of ‘scagliola’ artefacts. The Florentine naturalist G. Targioni Tozzetti wrote in 1769:

‘[in addition to alabaster]…the majority of scagliola (i.e. the raw mineral rock) also comes from Spicchiaiuola (a town near Volterra), and is calcinated in Florence to make tables, altar fronts etc…’ (see reference).

Tozzetti went on to say that ‘scagliaiuola is none other than selenite’. Selenite is a translucent form of gypsum found in abundance in the central and northern Apennines. It has a laminated structure that allows it to be split into sheets. The Romans used these sheets to make window panes, a practice which continued into the Middle Ages in Bologna, a major centre for selenite extraction. The name ‘scagliola’ was undoubtedly derived from the physical characteristics of raw selenite, which is brittle and breaks easily into flakes and chippings (scaglie in Italian). Once calcinated, the material loses its translucency and behaves like Plaster of Paris.

During the eighteenth century the word gradually came to be applied to imitation marble and hard-stone work, though by no means uniquely. Several other Italian terms survive, many of them specific to different regions; these include meschia or mestura (mixture) from Modena and Florence, pasta di marmo (marble paste) from Naples, and pietra di luna (moon stone) – which again refers to the natural stone rather than to its product. There is also the generic marmo di poveri (poor man’s marble) – no longer appropriate by today’s standards.

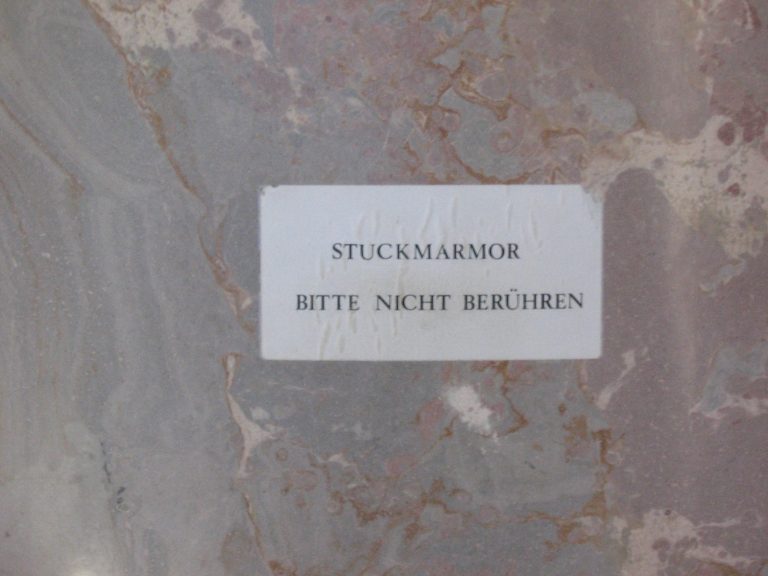

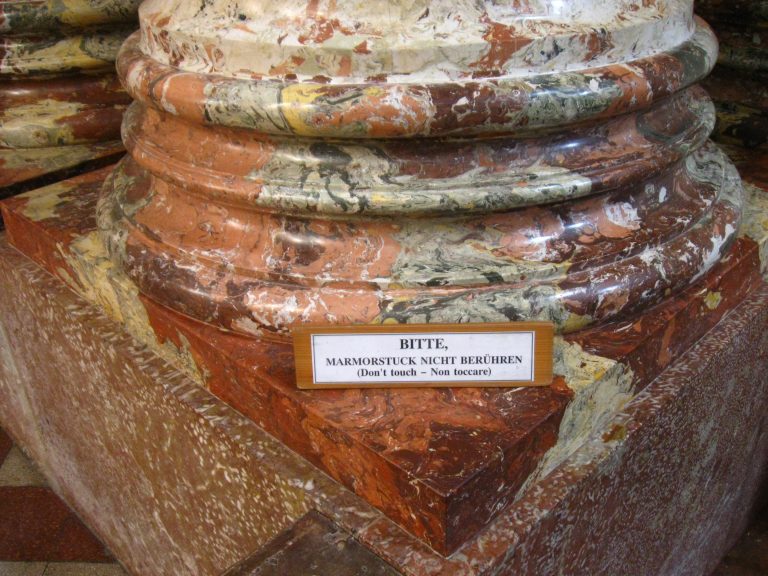

In the English-speaking world the term ‘scagliola’ has always referred to both architecturally formed and inlaid work. This is not the case in Europe, and particularly in German-speaking areas, where art historians and commentators have tended to differentiate between architectural and inlaid scagliola, seeing only the latter as true scagliola. In Germany, architectural forms of scagliola are called Stuckmarmor or (particularly in Austria) Kunstmarmor (stucco or artificial marble), and inlaid work Scagliola. In France the same distinction is made, using stuc marbre and scagliole or scaiole respectively. Italians sometimes use the expression finto marmo (artificial marble) to describe architectural scagliola. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ‘Bossi work’ was sometimes used to describe the practice of inlaying white marble table tops and chimney pieces with delicate neo-classical designs in coloured scagliola; many of these fashionable pieces were made by the Italian Pietro Bossi in Dublin at the end of the eighteenth century.

The opening footnote from Erwin Neumann’s article on Scagliola (quoted alongside) gives a good description of the ‘arbitrary’ nature of the division between architectural and inlaid scagliola, which Neumann himself considered to be problematic.

One could add that on both sides of the division the same materials are used and manipulated in much the same way to create the appearance of polished marble and hardstone; also that many scagliolists past and present have been active in both types of manufacture.

Reference: ‘Da Spicchiaiuola viene anche la maggior parte della Scagliaiuola. Che in Firenze si adopera calcinata per farne Tavole, Paliotti da Altare etc.’ G. Targioni Tozzetti Relazioni d’alcuni Viaggi Fatti in diverse Parti della Toscana Florence 1769, vol III p 134, quoted in Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997 Appendix V. 1.

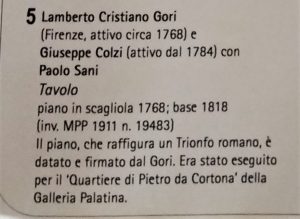

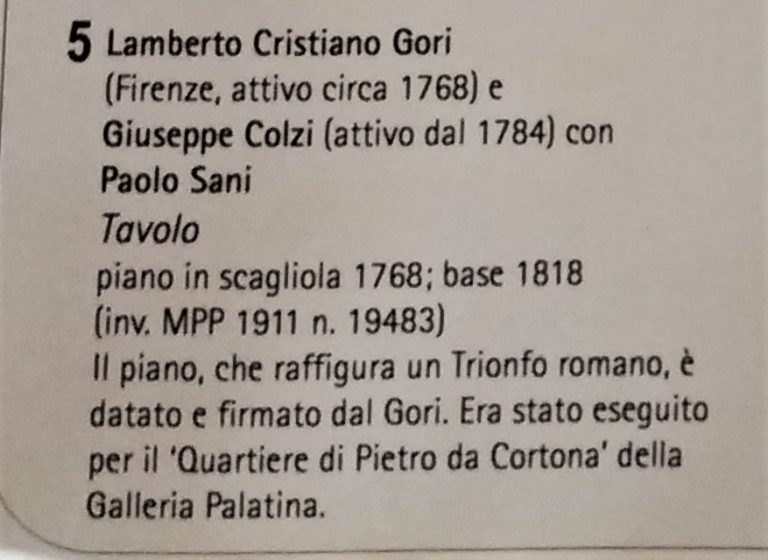

Scagliola table top by Lamberto Christiano Gori with museum description. Pitti Place, Florence.

‘Do not touch’ signs in Zwiefalten Abbey, Baden-Württemberg (LHS) and the Karlskirche, Vienna (RHS). (Click on images to enlarge).

‘…The distinction between artificial marble and Scagliola is of course entirely arbitrary, even though legitimised through common speech. Here it is made merely on the grounds of working practices, and perhaps it has become somewhat overstated. For these practical reasons we will exclude from the above definition the entire area of three-dimensional artificial marble forms, which other artistic rules consider to be true scagliola. In our sense scagliola is therefore primarily a planimetric construction, which shows a particular image on one side, which is roughly the case with the other inlaid and mosaic arts. Naturally points of cross-over occur, combinations of two and three dimensional forms.

The historiography of art has only taken very scant notice of the earlier existence of the technique of artificial marble. Of course there are here and there, and for the most part in rather concealed places, smaller reports concerning individual branches of the history of scagliola. These will be located and discussed at the appropriate places in the progress of this work; it should be noticed in advance however, that the comments of the 18th and early 19th centuries on the whole are more fertile than those of the later 19th and 20th. Only recently has technology and art history started again to remember the existence of this area, completely lost in oblivion.’

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152, Footnote 1. (my translation)

The origin of the word 'Scagliola', its use and other terms.

The Italian word scagliola (pronounced with a silent ‘g’), was in use in the Middle Ages long before the arrival of artificial marble. ‘Scagliaiuola’ was the name given in parts of central Italy to the mineral rock from which gypsum plaster (the basic ingredient of Plaster of Paris) was obtained. Only later did it become associated with the production of ‘scagliola’ artefacts. The Florentine naturalist G. Targioni Tozzetti wrote in 1769:

‘[in addition to alabaster]…the majority of scagliola (i.e. the raw mineral rock) also comes from Spicchiaiuola (a town near Volterra), and is calcinated in Florence to make tables, altar fronts etc…’ (see ref. below).

Tozzetti went on to say that ‘scagliaiuola’ is none other than selenite’. Selenite is a translucent form of gypsum found in abundance in the central and northern Apennines. It has a laminated structure that allows it to be split into sheets. The Romans used these sheets to make window panes, a practice which continued into the Middle Ages in Bologna, a major centre for selenite extraction. The name ‘scagliola’ was undoubtedly derived from the physical characteristics of raw selenite, which is brittle and breaks easily into flakes and chippings (scaglia in Italian). Once calcinated, the material loses its translucency and behaves like Plaster of Paris.

Scagliola table top by Lamberto Gori with museum description. Pitti Place, Florence.

During the eighteenth century the word gradually came to be applied to imitation marble and hard-stone work, though by no means uniquely. Several other Italian terms survive, many of them specific to different regions; these include meschia or mestura (mixture) from Modena and Florence, pasta di marmo (marble paste) from Naples, and pietra di luna (moon stone) – which again refers to the natural stone rather than to its product. There is also the generic marmo di poveri (poor man’s marble) – no longer appropriate by today’s standards.

In the English-speaking world the term ‘scagliola‘ has always referred to both architecturally formed and inlaid work. This is not the case in Europe, and particularly in German-speaking areas, where art historians and commentators have tended to differentiate between architectural and inlaid scagliola, seeing only the latter as true scagliola. In Germany, architectural forms of scagliola are called Stuckmarmor or (particularly in Austria) Kunstmarmor (stucco marble or artificial marble), and inlaid work Scagliola.

‘Do not touch’ signs in Zwiefalten Abbey, Baden-Württemberg (Top) and the Karlskirche, Vienna (Below).

In France the same distinction is made, using stuc marbre, and scagliole or scaiole respectively. Italians sometimes use the expression finto marmo (artificial marble) to describe architectural scagliola.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ‘Bossi work’ was sometimes used to describe the practice of inlaying white marble table tops and chimney pieces with delicate neo-classical designs in coloured scagliola; many of these fashionable pieces were made by the Italian Pietro Bossi in Dublin at the end of the eighteenth century.

The opening footnote from Erwin Neumann’s article on Scagliola (quoted below) gives a good description of the ‘arbitrary’ nature of the division between architectural and inlaid scagliola, which Neumann himself considered it to be problematic.

‘…The distinction between artificial marble and Scagliola is of course entirely arbitrary, even though legitimised through common speech. Here it is made merely on the grounds of working practices, and perhaps it has become somewhat overstated. For these practical reasons we will exclude from the above definition the entire area of three-dimensional artificial marble forms, which other artistic rules consider to be true scagliola. In our sense scagliola is therefore primarily a planimetric construction, which shows a particular image on one side, which is roughly the case with the other inlaid and mosaic arts. Naturally points of cross-over occur, combinations of two and three dimensional forms.

The historiography of art has only taken very scant notice of the earlier existence of the technique of artificial marble. Of course there are here and there, and for the most part in rather concealed places, smaller reports concerning individual branches of the history of scagliola. These will be located and discussed at the appropriate places in the progress of this work; it should be noticed in advance however, that the comments of the 18th and early 19th centuries on the whole are more fertile than those of the later 19th and 20th. Only recently has technology and art history started again to remember the existence of this area, completely lost in oblivion.’

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-152, Footnote 1. (my translation)

One could add that on both sides of the division the same materials are used and manipulated in much the same way to create the appearance of polished marble and hardstone; and that many scagliolists past and present have been active in both types of manufacture.

Reference: ‘Da Spicchiaiuola viene anche la maggior parte della Scagliaiuola. Che in Firenze si adopera calcinata per farne Tavole, Paliotti da Altare etc.’ G. Targioni Tozzetti Relazioni d’alcuni Viaggi Fatti in diverse Parti della Toscana Florence 1769, vol III p 134, quoted in Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola, l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997 Appendix V. 1.