The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

The Fistulator family business continued to produce scagliola for the Munich Residence for another generation, but there were no projects that matched the scale and complexity of Blasius’s and Wilhelm’s achievements. Most of their activity now involved refurbishment and reconstruction.

In 1674, just five years after Wilhelm Fistulator’s death, a major fire destroyed the Stone Rooms (see chapter 10). All the scagliola had to be replaced, and the work lasted on and off for the next twenty-five years, much to the dissatisfaction of the court. During the repairs, the Fistulators lost their position of pre-eminence. The growing number of people who had been involved in the various stages of manufacture made it impossible to keep the technique a secret, and the court’s monopoly on the manufacture and use of Stuckmarmor became increasingly unenforceable. Independent scagliolists began operating outside the court and before long outside the Bavarian state.

In Maximilian’s time this would not have been tolerated; but under his successors the court, while continuing to protest regularly about perceived abuses of its authority, was itself not averse to employing craftsmen from outside the Fistulator circle if they could undercut their ‘in-house’ rivals or provide work of a higher quality

By the beginning of the eighteenth century the material was no longer considered exclusive and its appeal began to fade. European courts were moving away from the grand but uncomfortable ceremonial interiors of the 1600s, in which marble and scagliola had played such significant roles. The new emphasis was towards lighter and less formal living arrangements, influenced by the playful Régence decoration that first appeared during the minority of Louis XV, and was the generational forerunner of Rococo.

Franciscus Fistulator (1626-1660) pre-deceased his father Wilhelm, after a short career in which, as his petitions to the court demonstrate, he was continually short of money. His only recorded solo work is a tabletop which has not been possible to identify, for which he received an ex gratia payment of 150 guilders. When he died aged thirty-four after a six month illness, his affairs were in such poor state that his wife had to petition the court for money to bury him and pay off his debts. He left four children, none of whom became scagliolists.

Ferdinand Fistulator (1640-1679), brother of Franciscus, took over as head of the business in the early 1660s after his father became unable to work through infirmity. He remained in charge until his own death at the age of thirty-nine. He too was constantly short of money and approached the court on several occasions requesting a pay rise or back-pay that was due to him. It is known that he was involved with the reconstruction of the Stone Rooms, but there is no record of any individual work by him. He had three children, and as in the case of his brother Franciscus, none of them became scagliolists.

Andreas Römer (1646-1707). Ferdinand was succeeded as head of the business by his brother-in-law, Andreas Römer. In 1666 he had married Maria Theresia, the third of Wilhelm’s children to become a scagliolist. The Elector Ferdinand Maria gave them a wedding present of a silver drinking vessel. Römer, whose father was a cook at the royal court from 1653-85, had trained as a painter. As a result of his marriage, he was given permission to learn the technique of scagliola. (The Elector noted approvingly that with his background, he would not need to go through the essential preliminary training in drawing and painting).

Römer’s career reveals how precarious the fortunes of a court artist or craftsman could be in seventeenth century Germany, and the records allow us to follow his decline. In 1666, a few days before his wedding, he took the oath of secrecy. His initial salary was set at 300 guilders, only 20 guilders below that of Ferdinand Fistulator, the head of the business. Römer was popular with the Italian Electoress, Henrietta Adelaide of Savoy, for whom he carried out work at the nearby country residence of Nymphenburg. When she died in 1676, she left him 85 guilders in her will. He was then ordered back to the Munich Residence to work alongside Ferdinand on the repairs to the Stone Rooms.

In 1679 Ferdinand died and Römer took over as head of the firm. In the same year, Elector Ferdinand Maria died and was succeeded by Maximilian II Emmanuel (r. 1679-1726). Working under the court architect Enrico Zucalli, Römer supervised the repairs to the Stone Rooms and continued to supply pictorial panels, door surrounds and tabletops in the same way as his predecessors. Most of his work was lost in the second great fire at the Residence in 1729.

In 1686 he was sent at short notice to Margrave Wilhelm Ludwig von Baden (known as ‘Turkish Louis’ because he led the Imperial armies in several successful campaigns against the Turks in Hungary). The Margrave was fascinated by scagliola, and for a year and a half, Römer and four assistants worked for him on various commissions; on leaving, he obtained a document stating that he and his team had performed to the Margrave’s complete satisfaction.

Returning to Munich in the second half of 1687, Römer waited in vain for instructions. In his absence he had fallen from favour and his fortunes now went into steep decline. In 1689 he was dismissed by the newly appointed director of the Office of Buildings, and went unpaid for the next four years. This pushed him into debt and extreme poverty and damaged his health. The court also refused him permission to take on outside work, and he was unable to accept a commission from the Jesuits to build two altars. Even after he was reappointed in 1692, at a reduced salary, he was denied access to a workshop in the palace, and his allowance for materials was stopped.

In 1695 a rival scagliolist, Wilhelm Langenbuecher, who had been employed by the court since 1680, was given the commission for finishing the remaining work on the repairs to the Stone Rooms. He and Römer had been asked to provide separate estimates, and Langenbuecher significantly undercut Römer in terms of cost and time. The infuriated Römer wrote a letter of protest to the Elector claiming that Langenbuecher was a bungler who could neither draw nor paint, and was only capable of doing repairs and patches. He, Römer, would be ashamed to turn out such ‘buttermilk’ (Buttermilch). Max Emmanuel and Zucalli were unimpressed by this outburst, Zucalli stating that Römer’s pictorial work was no better than Langenbuecher’s, who was cheaper and faster.

Römer continued to receive his basic salary, but he was shut out of court service and refused permission to work elsewhere. He contracted dropsy, a form of oedema, which caused him extreme breathlessness and required him to sleep sitting upright in a chair. In 1701 he was re-employed, despite his ‘slow hands’ and his ‘extravagant use of costly pigments’, but his financial difficulties remained unaddressed and he continued to ask for the substantial back-pay that was owed to him. In 1704 he offered to take back three tabletops he had made for the court, for which he had never been paid, and which he thought he could sell elsewhere. He was told he could have two, but they had been badly stored and were so water damaged that he refused to accept them. Finally, in 1706, sick and at the end of his working life, he was informed by the court that it had been decided to let him go – ‘as he himself had always requested’ – since artificial marble was no longer held in much esteem. Within six months he was dead. His wife received two guilders to help with his funeral expenses.

Maria Theresia Römer (b. Fistulator 1634-c.1707). Maria Theresia was by all accounts a skilled scagliolist, and her presence at court did not go unnoticed. In 1685, the Office of Buildings registered a complaint about her: she was considered the most skilled member of Römer’s workshop, but she had been working away from Munich, and even beyond Electoral Bavaria. She must restrict her activities to the court.

When Römer was away in Baden-Baden (1686-87), she took his place as acting head of the workshop and was considered as hard-working as anyone else, capable of working unsupervised, and in fact leading the team; it was said that her skills were superior to those of her husband. She also had a better relationship with the Elector Max Emmanuel; in one of his many letters requesting payment, this time on behalf of his wife, Römer reminded the Elector how often he had seen her at work, sometimes stopping to talk to her.

Maria Theresia spent eight years in the service of the court. She ceased to be given work once her husband had fallen from favour, and if he is to be believed, she too went largely unpaid. According to Römer, she was only ever paid for the first three months of the period that she ran the workshop in Munich, while he was away in Baden-Baden.

After Römer’s death, she requested that an outstanding sum of 250 guilders be paid to her. This was refused, on the grounds that the court had more pressing bills to settle. The following year, 1707, she was awarded a one-off payment of three guilders, on account of her ‘high neediness’, and later, a weekly allowance of thirty kreuzer (half a guilder); after this, no more was heard of her. Maria Theresia was the last of the Fistulator scagliolists.

Scagliolists at the Munich Court without family connections to the Fistulators.

Willhelm Langenbuecher (1651-1719), who replaced Andreas Römer (see above), had originally been taken on to assist him with the repairs to the Stone Rooms; whether he had prior knowledge of the technique or learnt it on the job is unknown. Langenbuecher remained in charge of scagliola works at the court until his death; in the early eighteenth century he worked on the Hofkapelle and carried out refurbishment work in the Reiche Kapelle. He received permission to train his two sons Benedikt (d. 1741) and Anton (d. 1773), both of whom continued in royal service after his death. They were responsible for transferring and fitting Wilhelm Fistulator’s scagliola panels from the Trier Rooms to the Stucco Cabinet at Schleissheim in 1724-25 (see Chapter 12).

At the same time another scagliolist, Hans Georg Baader (dates unkown), installed a second set of panels from the Trier Rooms in the Kammerkapelle at Schleissheim, directly above the Stucco Cabinet. He added an altar front and some infill panels in Rococo style, and was also responsible for laying the red, yellow and grey marble floor (ibid.).

An earlier scagliolist from outside the immediate Fistulator family circle was Franz Viechter (dates unknown) from Kitzbühl, initially employed by the court in 1658 as a stuccoist. (It may have been decided to train him alongside Ferdinand Fistulator, following the early death of Franciscus in 1659). Viechter successfully sought permission to leave the court in 1662, but re-appeared in 1669, and was responsible for various inlaid panels as well as working on the repairs to the Stone Rooms. He was dismissed in 1689 at the same time as Röhmer. Two of his works have survived and are held in the Bavarian National Museum, a pair of tondos made in 1670 and 1672. The first shows a formal park with a figure running across the foreground, the second an architectural interior. The style, with strong use of perspective, is reminiscent of Wilhelm Fistulator’s, but also shows a move away from the strict imitation of Pietre Dure work towards a pictorial style.

Also mentioned in the court documents is Benno Braittenbach (d. 1700) who was employed as an assistant from 1677. From 1681 He worked as a scagliolist on the Stone Rooms alongside Wilhelm Langenbuecher.

The scagliola in the church of St. Lawrence, Kempten (1666-1670)

The first monumental church to be built in Germany after the devastation of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) was the Basilica of St. Lawrence (begun 1652) in the imperial free city of Kempten, some sixty miles south west of Munich. It was also the first building in Southern Germany to see the extensive use of scagliola under the patronage of the Catholic Church as opposed to the Bavarian court.

Between 1666 and 1670 a series of inlaid scagliola panels was installed, the majority of which can still be seen today, though the original locations within the church have changed.

• An altar front, originally in the main altar but subsequently moved to the north altar of the choir; it shows the Virgin’s monogram in a central oval, surrounded by flowers and foliage on a black background. (The red scagliola panelling and columns that form the altar surround and reredos are from a later period).

• Two arched panels with floral arrangements in amphora on either side of the altar front.

• Six pilaster strips on the diagonal faces of the choir piers, with stylised floral candelabra on a black background, recessed in a plain yellowish-brown moulding marbled with red flecks.

• Thirty-five arched panels set into the backs of the choir stall seats. The panels bear a variety of motifs: amphora with foliage, coats of arms, architectural perspectives, and different landscapes portraying churches, castles, house, bridges, and ruins. Some of the scenes include people and animals.

• Above each choir back and set into a carved timber roll-work cartouche, a further oval panel with a small design of foliage and birds on a black background.

The influence of Wilhelm Fistulator’s designs and subject matter is plain to see in these panels and choir stall backs but there are striking differences: the imitations of marble are simplistic, with fewer colours and vey basic figuring used, and the colours themselves are less vibrant; the pictures themselves lack the precision and detail of Wilhelm’s, and they imitate painting rather than Pietra Dure inlay. Nevertheless they have great charm, and the quantity and diversity of the work makes it a considerable achievement.

The identity of the scagliolist responsible is unknown, though the records refer to a woman stuccoist (Frau Stuckhatorin). The most obvious candidate would be Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, perhaps assisted by her daughter Maria Theresia and her son-in-law Andreas Römer. Maria Liebhardt argues the case on the grounds that, although inferior in quality to the Munich Residence, the St. Lawrence scagliola is definitely not the work of a beginner; and given the strict monopoly in existence until the 1650s, only someone from the Fistulator circle would have had the ability and experience to produce it. Liebhardt also sees stylistic similarities with the scagliola work in the Munich Grottenzimmer.

Nevertheless, the difference in quality is hard to overlook, and doubts still remain as to the identity of Kempten’s ‘Frau Stukhatorin’.

References: Michaela Liebhardt, Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987.

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.

Two examples of Rococo palace interiors in and around Munich from the first half of the 18th Century.

The Picture Gallery, Munich Residence, commissioned in 1726. The architect was the French-trained Joseph Effner (1687-1745).*

Ceiling detail from The Amalienburg, Nymphenburg Palace Park, comissioned 1734, designed by Francois Cuvilliés (1695-1768) who trained in Paris alongside Effner and eventually replaced him as Munich Court Architect.*

Scagliola work in and around Munich by craftsmen working independently of the Fistulator family circle. (1670s – 1720s).

Scagliola panels in the Stucco Cabinet at Schleissheim Castle. Made in the 1620s by Wilhelm Fistulator for the Trier Rooms in the Munich Residence (see Chapter 12), they were transferred to Schleissheim in the 1720s and installed in the Stucco Cabinet by Benedikt and Anton Langenbuecher, sons of Wilhelm Langenbucher.*

Rococo scagliola altar front by Hans Georg Bader, Kammerkapelle, Schleissheim 1720s. Bader was also responsible for installing a set of Wilhelm Fistulator’s panels from the Trier Rooms in the Kammerkapelle (see Chapter 12).*

Two scagliola tondos (1670 & 1672). The dramatic use of perspective and chiaroscuro shows the influence of Wilhelm Fistulator; but there are also signs of a move away from the strict imitation of Pietre Dure work towards a more fluid and pictorial style. (Franz Viechter, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich). Click on details to enlarge.*

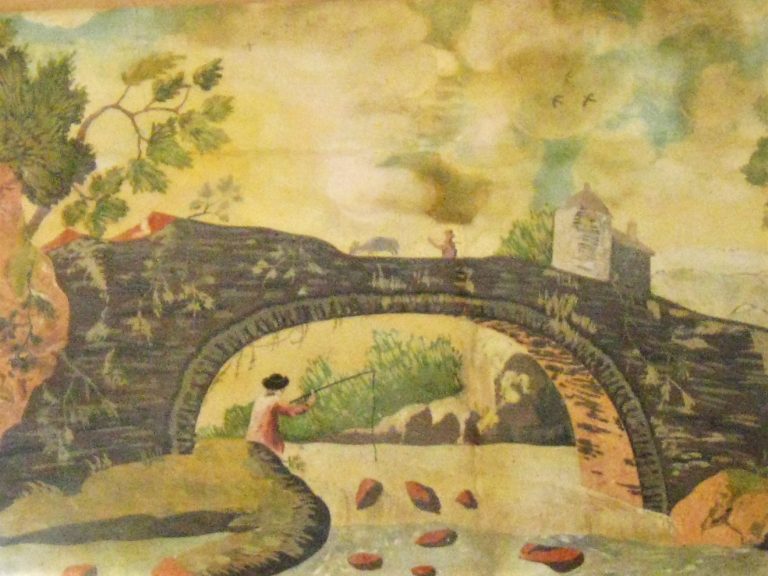

Two small riverscapes, probably from the third quarter of the 17th century. They recall the scagliola panels in the choir chair-backs in the Basilica of St. Lawrence in Kempten, Bavaria (see below).*

Scagliola work in the Basilica Church of St. Lawrence, Kempten (1666-1670)

Scagliola altar-front and arched side-panels with floral designs, flanked by two scagliola pilaster strips with candelabra. (1666-68, by ‘Frau Stukhatorin’, probably Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, Lorenzkirche, Kempten). Click on details to enlarge.

Choir back panels in scagliola. (1666-68, by ‘Frau Stukhatorin’, probably Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, Lorenzkirche, Kempten). Click on photos to enlarge.

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze,

The Fistulator family business continued to produce scagliola for the Munich Residence for another generation, but there were no projects that matched the scale and complexity of Blasius’s and Wilhelm’s achievements. Most of their activity now involved refurbishment and reconstruction.

In 1674, just five years after Wilhelm Fistulator’s death, a major fire destroyed the Stone Rooms (see chapter 10). All the scagliola had to be replaced, and the work lasted on and off for the next twenty-five years, much to the dissatisfaction of the court. During the repairs, the Fistulators lost their position of pre-eminence. The growing number of people who had been involved in the various stages of manufacture made it impossible to keep the technique a secret, and the court’s monopoly on the manufacture and use of Stuckmarmor became increasingly unenforceable. Independent scagliolists began operating outside the court and before long outside the Bavarian state.

In Maximilian’s time this would not have been tolerated; but under his successors the court, while continuing to protest regularly about perceived abuses of its authority, was itself not averse to employing craftsmen from outside the Fistulator circle if they could undercut their ‘in-house’ rivals or provide work of a higher quality.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century the material was no longer considered exclusive and its appeal began to fade. European courts were moving away from the grand but uncomfortable ceremonial interiors of the 1600s, in which marble and scagliola had played such significant roles. The new emphasis was towards lighter and less formal living arrangements, influenced by the playful Régence decoration that first appeared during the minority of Louis XV, and was the generational forerunner of Rococo.

Two examples of Rococo palace interiors in and around Munich from the first half of the 18th Century.

The Picture Gallery, Munich Residence, commissioned in 1726. The architect was the French-trained Joseph Effner (1687-1745).*

Ceiling detail from The Amalienburg, Nymphenburg Palace Park, comissioned 1734, designed by Francois Cuvilliés (1695-1768) who trained in Paris alongside Effner and eventually replaced him as Munich Court Architect.*

Franciscus Fistulator (1626-1660) pre-deceased his father Wilhelm, after a short career in which, as his petitions to the court demonstrate, he was continually short of money. His only recorded solo work is a tabletop which has not been possible to identify, for which he received an ex gratia payment of 150 guilders. When he died aged thirty-four after a six month illness, his affairs were in such poor state that his wife had to petition the court for money to bury him and pay off his debts. He left four children, none of whom became scagliolists.

Ferdinand Fistulator (1640-1679), brother of Franciscus, took over as head of the business in the early 1660s after his father became unable to work through infirmity. He remained in charge until his own death at the age of thirty-nine. He too was constantly short of money and approached the court on several occasions requesting a pay rise or back-pay that was due to him. It is known that he was involved with the reconstruction of the Stone Rooms, but there is no record of any individual work by him. He had three children, and as in the case of his brother Franciscus, none of them became scagliolists.

An early scagliolist from outside the immediate Fistulator family circle was Franz Viechter (dates unknown) from Kitzbühl, initially employed by the court in 1658 as a stuccoist. (It may have been decided to train him alongside Ferdinand Fistulator, following the early death of Franciscus in 1659). Viechter successfully sought permission to leave the court in 1662, but re-appeared in 1669, and was responsible for various inlaid panels as well as working on the repairs to the Stone Rooms. He was dismissed in 1689 at the same time as Andreas Röhmer (see below). Two of his works have survived and are held in the Bavarian National Museum, a pair of tondos made in 1670 and 1672. The first a formal park with a figure running across the foreground, the second an architectural interior. The style, with strong use of perspective, is reminiscent of Wilhelm Fistulator’s, but also shows a move away from the strict imitation of Pietre Dure work towards a pictorial style.

Two scagliola tondos (1670 & 1672). The dramatic use of perspective and chiaroscuro shows the influence of Wilhelm Fistulator; but there are also signs of a move away from the strict imitation of Pietre Dure work towards a more fluid and pictorial style. (Franz Viechter, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich). *

Also mentioned in the court documents is Benno Braittenbach (d. 1700) who was employed as an assistant from 1677. From 1681 He worked as a scagliolist on the Stone Rooms alongside Wilhelm Langenbuecher (see below).

Andreas Römer (1646-1707). Ferdinand was succeeded as head of the business by his brother-in-law, Andreas Römer. In 1666 he had married Maria Theresia, the third of Wilhelm’s children to become a scagliolist. The Elector Ferdinand Maria gave them a wedding present of a silver drinking vessel. Römer, whose father was a cook at the royal court from 1653-85, had trained as a painter. As a result of his marriage, he was given permission to learn the technique of scagliola. (The Elector noted approvingly that with his background, he would not need to go through the essential preliminary training in drawing and painting).

Römer’s career reveals how precarious the fortunes of a court artist or craftsman could be in seventeenth century Germany, and the records allow us to follow his decline. In 1666, a few days before his wedding, he took the oath of secrecy. His initial salary was set at 300 guilders, only 20 guilders below that of Ferdinand Fistulator, the head of the business. Römer was popular with the Italian Electoress, Henrietta Adelaide of Savoy, for whom he carried out work at the nearby country residence of Nymphenburg. When she died in 1676, she left him 85 guilders in her will. He was then ordered back to the Munich Residence to work alongside Ferdinand on the repairs to the Stone Rooms.

In 1679 Ferdinand died and Römer took over as head of the firm. In the same year, Elector Ferdinand Maria died and was succeeded by Maximilian II Emmanuel (r. 1679-1726). Working under the court architect Enrico Zucalli, Römer supervised the repairs to the Stone Rooms and continued to supply pictorial panels, door surrounds and tabletops in the same way as his predecessors. Most of his work was lost in the second great fire at the Residence in 1729.

In 1686 he was sent at short notice to Margrave Wilhelm Ludwig von Baden (known as ‘Turkish Louis’ because he led the Imperial armies in several successful campaigns against the Turks in Hungary). The Margrave was fascinated by scagliola, and for a year and a half, Römer and four assistants worked for him on various commissions; on leaving, he obtained a document stating that he and his team had performed to the Margrave’s complete satisfaction.

Returning to Munich in the second half of 1687, Römer waited in vain for instructions. In his absence he had fallen from favour and his fortunes now went into steep decline. In 1689 he was dismissed by the newly appointed director of the Office of Buildings, and went unpaid for the next four years. This pushed him into debt and extreme poverty and damaged his health. The court also refused him permission to take on outside work, and he was unable to accept a commission from the Jesuits to build two altars. Even after he was reappointed in 1692, at a reduced salary, he was denied access to a workshop in the palace, and his allowance for materials was stopped.

In 1695 a rival scagliolist, Wilhelm Langenbuecher, who had been employed by the court since 1680, was given the commission for finishing the remaining work on the repairs to the Stone Rooms. He and Römer had been asked to provide separate estimates, and Langenbuecher significantly undercut Römer in terms of cost and time. The infuriated Römer wrote a letter of protest to the Elector claiming that Langenbuecher was a bungler who could neither draw nor paint, and was only capable of doing repairs and patches. He, Römer, would be ashamed to turn out such ‘buttermilk’ (Buttermilch). Max Emmanuel and Zucalli were unimpressed by this outburst, Zucalli stating that Römer’s pictorial work was no better than Langenbuecher’s, who was cheaper and faster.

Römer continued to receive his basic salary, but he was shut out of court service and refused permission to work elsewhere. He contracted dropsy, a form of oedema, which caused him extreme breathlessness and required him to sleep sitting upright in a chair. In 1701 he was re-employed, despite his ‘slow hands’ and his ‘extravagant use of costly pigments’, but his financial difficulties remained unaddressed and he continued to ask for the substantial back-pay that was owed to him. In 1704 he offered to take back three tabletops he had made for the court, for which he had never been paid, and which he thought he could sell elsewhere. He was told he could have two, but they had been badly stored and were so water damaged that he refused to accept them. Finally, in 1706, sick and at the end of his working life, he was informed by the court that it had been decided to let him go – ‘as he himself had always requested’ – since artificial marble was no longer held in much esteem. Within six months he was dead. His wife received two guilders to help with his funeral expenses.

Two small riverscapes, probably from the third quarter of the 17th century. They recall the scagliola panels in the choir chair-backs in the Basilica of St. Lawrence in Kempten, Bavaria (see below).*

Maria Theresia Römer (b. Fistulator 1634-c.1707). Maria Theresia was by all accounts a skilled scagliolist, and her presence at court did not go unnoticed. In 1685, the Office of Buildings registered a complaint about her: she was considered the most skilled member of Römer’s workshop, but she had been working away from Munich, and even beyond Electoral Bavaria. She must restrict her activities to the court.

When Römer was away in Baden-Baden (1686-87), she took his place as acting head of the workshop and was considered as hard-working as anyone else, capable of working unsupervised, and in fact leading the team; it was said that her skills were superior to those of her husband. She also had a better relationship with the Elector Max Emmanuel; in one of his many letters requesting payment, this time on behalf of his wife, Römer reminded the Elector how often he had seen her at work, sometimes stopping to talk to her.

Maria Theresia spent eight years in the service of the court. She ceased to be given work once her husband had fallen from favour, and if he is to be believed, she too went largely unpaid. According to Römer, she was only ever paid for the first three months of the period that she ran the workshop in Munich, while he was away in Baden-Baden.

After Römer’s death, she requested that an outstanding sum of 250 guilders be paid to her. This was refused, on the grounds that the court had more pressing bills to settle. The following year, 1707, she was awarded a one-off payment of three guilders, on account of her ‘high neediness’, and later, a weekly allowance of thirty kreuzer (half a guilder); after this, no more was heard of her. Maria Theresia was the last of the Fistulator scagliolists.

Willhelm Langenbuecher (1651-1719), who replaced Andreas Römer (see above), had originally been taken on to assist him with the repairs to the Stone Rooms; whether he had prior knowledge of the technique or learnt it on the job is unknown. Langenbuecher remained in charge of scagliola works at the court until his death; in the early eighteenth century he worked on the Hofkapelle and carried out refurbishment work in the Reiche Kapelle. He received permission to train his two sons Benedikt (d. 1741) and Anton (d. 1773), both of whom continued in royal service after his death. They were responsible for transferring and fitting Wilhelm Fistulator’s scagliola panels from the Trier Rooms to the Stucco Cabinet at Schleissheim in 1724-25 (see Chapter 12).

Scagliola panels in the Stucco Cabinet at Schleissheim Castle. Made in the 1620s by Wilhelm Fistulator for the Trier Rooms in the Munich Residence (see Chapter 12), they were transferred to Schleissheim in the 1720s and installed in the Stucco Cabinet by Benedikt and Anton Langenbuecher, sons of Wilhelm Langenbucher.*

At the same time another scagliolist, Hans Georg Baader (dates unkown), installed a second set of panels from the Trier Rooms in the Kammerkapelle at Schleissheim, directly above the Stucco Cabinet. He added an altar front and some infill panels in Rococo style, and was also responsible for laying the red, yellow and grey marble floor (ibid.).

Rococo scagliola altar front by Hans Georg Bader, Kammerkapelle, Schleissheim 1720s. Bader was also responsible for installing a set of Wilhelm Fistulator’s panels from the Trier Rooms in the Kammerkapelle (see Chapter 12).*

The scagliola in the church of St. Lawrence, Kempten (1666-1670)

The first monumental church to be built in Germany after the devastation of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) was the Basilica of St. Lawrence (begun 1652) in the imperial free city of Kempten, some sixty miles south west of Munich. It was also the first building in Southern Germany to see the extensive use of scagliola under the patronage of the Catholic Church as opposed to the Bavarian court.

Between 1666 and 1670 a series of inlaid scagliola panels was installed, the majority of which can still be seen today, though their original locations within the church have changed.

• An altar front, originally part of the main altar but subsequently moved to the north altar of the choir; it shows the Virgin’s monogram in a central oval, surrounded by flowers and foliage on a black background. (The red scagliola surround is from a later period).

• Two arched panels with floral arrangements in amphora on either side of the altar front.

• Six pilaster strips on the diagonal faces of the choir piers, with stylised floral candelabra on a black background, recessed in a plain yellowish-brown moulding marbled with red flecks.

Scagliola altar-front and one of two arched side-panels with floral designs, one of six scagliola pilaster strips with candelabra design. (1666-68, by ‘Frau Stukhatorin’, probably Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, Lorenzkirche, Kempten). Click on details to enlarge.

• Thirty-five arched panels set into the backs of the choir stall seats. The panels bear a variety of motifs: amphora with foliage, coats of arms, architectural perspectives, and different landscapes portraying churches, castles, house, bridges, and ruins. Some of the scenes include people and animals.

• Above each choir back and set into a carved timber roll-work cartouche, a further oval panel with a small design of foliage and birds on a black background.

Choir back panels in scagliola. (1666-68, by ‘Frau Stukhatorin’, probably Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, Lorenzkirche, Kempten). Click on photos to enlarge.

The influence of Wilhelm Fistulator’s designs and subject matter is plain to see in these panels but there are striking differences: the imitations of marble are simplistic, with fewer colours and vey basic figuring used, and the colours themselves are less vibrant; the pictures themselves lack the precision and detail of Wilhelm’s, and they imitate painting rather than Pietra Dure inlay. Nevertheless they have great charm, and the quantity and diversity of the work makes it a considerable achievement.

The identity of the scagliolist responsible is unknown, though the records refer to a woman stuccoist (Frau Stuckhatorin). The most obvious candidate would be Barbara Fistulator, wife of Wilhelm, perhaps assisted by her daughter Maria Theresia and her son-in-law Andreas Römer. Maria Liebhardt argues the case on the grounds that, although inferior in quality to the Munich Residence, the St. Lawrence scagliola is definitely not the work of a beginner; and given the strict monopoly in existence until the 1650s, only someone from the Fistulator circle would have had the ability and experience to produce it. Liebhardt also sees stylistic similarities with the scagliola work in the Munich Grottenzimmer. Nevertheless, the difference in quality is hard to overlook, and doubts still remain as to the identity of Kempten’s ‘Frau Stukhatorin’.

References: Michaela Liebhardt, Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987.

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze,