I. The Uses of Scagliola

Scagliola is used in two different ways: firstly, to imitate the marble and hardstone inlay work known as Pietre Dure; and secondly, as an imitation marble for internal architecture.

Inlaid Scagliola. The material first appeared in southern Germany in the 1580s, and quickly received the endorsement of royalty and the Catholic Church. The Dukes and Electors of Bavaria used it to considerable effect in the Munich Residence, drawing interest from many of Europe’s rulers, including the Holy Roman Emperor.

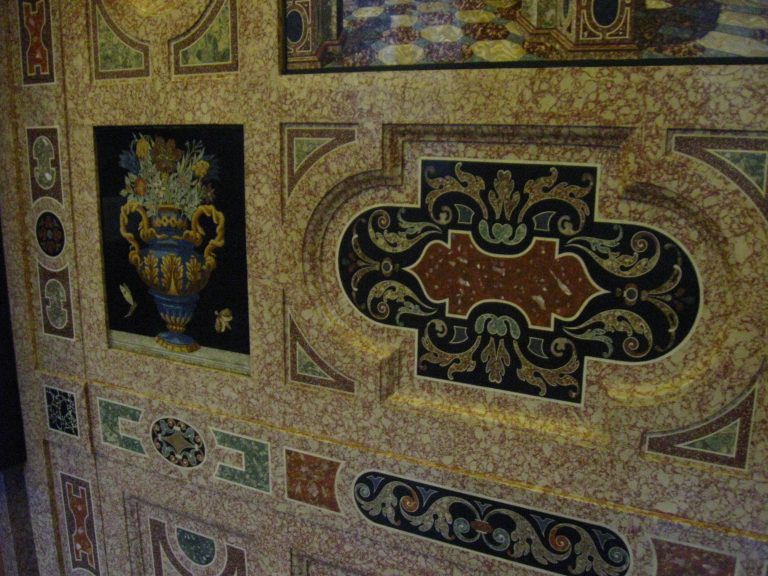

During the 17th and 18th centuries scagliola was used extensively in areas of central and northern Italy to make altar fronts. The work followed the example of contemporary Roman and Florentine inlaid marble and Pietre Dure, using brightly coloured decorative and religious motifs set in a dense black background. As the scagliolists became more accomplished, they developed techniques for producing pictorial work which eventually took them beyond the scope of Pietre Dure.

The material was also used to make decorative table tops, panels for display cabinets, and chimney pieces. These objects became increasingly sophisticated, finding a ready market with wealthy aristocrats and collectors, notably the British and French Grand Tourists of the eighteenth century. There are many examples of inlaid scagliola in the palaces, stately homes and museums of Europe. Antique scagliola table tops and chimney pieces are very collectable and frequently appear at auction.

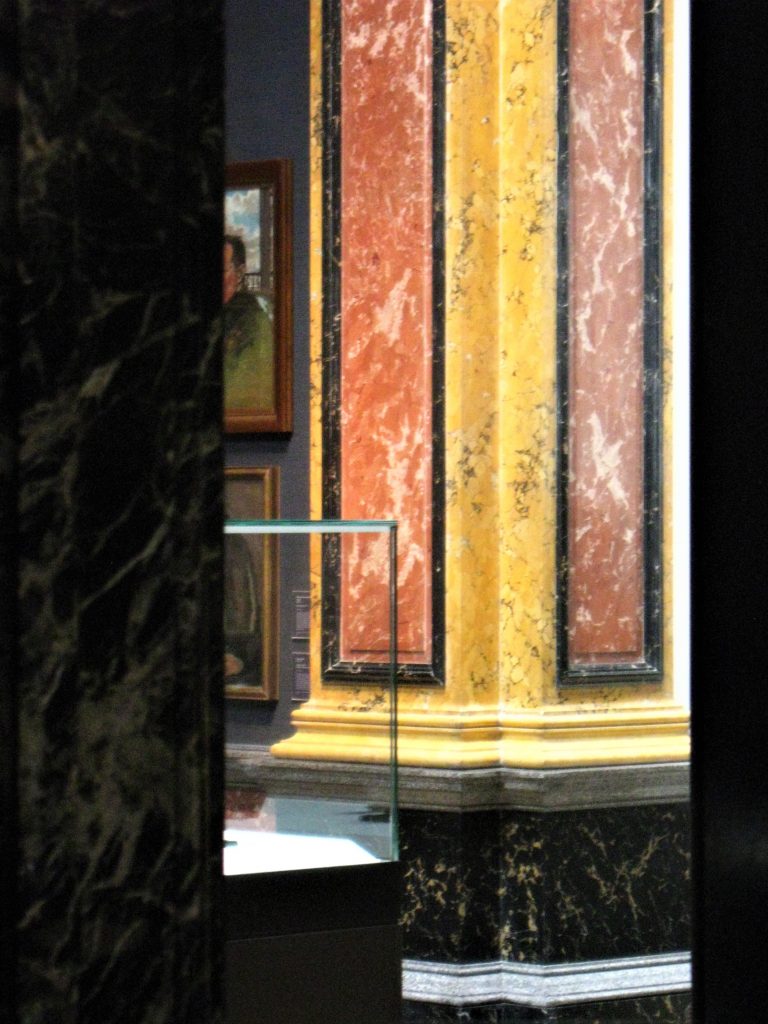

Architectural Scagliola. Often mistaken for the real thing, scagliola is used to imitate marble surfaces for all forms of internal architecture: columns and pilasters, door casements and altar surrounds, chimney pieces, wall panels, and occasionally floors. It is frequently used to make half-columns, pedestals and plinths for the display of sculpture.

The most flamboyant architectural scagliola is found in the eighteenth century Baroque and Rococo churches of Southern Germany, but the material is equally at home in the Neoclassical houses of Georgian and Regency England. It can be seen in many of the public and semi-public buildings of the nineteenth century: museums and art galleries, town halls and theatres, hotels, libraries, banks and private clubs. It was used extensively for grand architectural projects in Imperial Russia and the United States.

Although not load-bearing, scagliola is ideal for cladding structural elements in a building, and its comparative lightness allows it to be used in areas where stone and marble would be impractical. Its main limitations are two-fold: it cannot be used outdoors or in damp conditions; and because it is so labour-intensive, it is expensive – today often more so than marble, which has become industrialised at all stages of production.

Inlaid scagliola panelling, Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence, c. 1605 (Reconstruction).

© Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photo by Richard Feroze,

Altar Front by Giovan Marco Barzelli c. 1680. Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena

Rococo scagliola pulpit at Zwiefalten Abbey, Baden-Württemburg c.1750

19th century Scagliola at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

(Click on images to enlarge.)

I. The Uses of Scagliola

Scagliola is used in two different ways: firstly, to imitate the marble and hardstone inlay work known as Pietre Dure; and secondly, as an imitation marble for internal architecture.

Inlaid Scagliola. The material first appeared in southern Germany in the 1580s, and quickly received the endorsement of royalty and the Catholic Church. The Dukes and Electors of Bavaria used it to considerable effect in the Munich Residence, drawing interest from many of Europe’s rulers, including the Holy Roman Emperor.The

Inlaid scagliola panelling, Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence, c. 1605 (Reconstruction).

© Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photo by Richard Feroze

During the 17th and 18th centuries scagliola was used extensively in areas of central and northern Italy to make altar fronts. The work followed the example of contemporary Roman and Florentine inlaid marble and Pietre Dure, using brightly coloured decorative and religious motifs set in a dense black background. As the scagliolists became more accomplished, they developed techniques for producing pictorial work which eventually took them beyond the scope of Pietre Dure.

Altar Front by Giovan Marco Barzelli c. 1680.

Abbey Church of San Pietro, Modena

Scagliola was also used to make decorative table tops, panels for display cabinets, and chimney pieces. These objects became increasingly sophisticated, finding a ready market with wealthy aristocrats and collectors, notably the British and French Grand Tourists of the eighteenth century. There are many examples of inlaid scagliola in the palaces, stately homes and museums of Europe. Antique scagliola table tops and chimney pieces are very collectable and frequently appear at auction.

Architectural Scagliola. Often mistaken for the real thing, scagliola is used to imitate marble surfaces for all forms of internal architecture: columns and pilasters, door casements and altar surrounds, chimney pieces, wall panels, and occasionally floors. It is frequently used to make half-columns, pedestals and plinths for the display of sculpture.

Rococo scagliola pulpit at Zwiefalten Abbey,

Baden-Württemburg c.1750

The most flamboyant architectural scagliola is found in the eighteenth century Baroque and Rococo churches of Southern Germany, but the material is equally at home in the Neoclassical houses of Georgian and Regency England. It can be seen in many of the public and semi-public buildings of the nineteenth century: museums and art galleries, town halls and theatres, hotels, libraries, banks and private clubs. It was used extensively for grand architectural projects in Imperial Russia and the United States. Although not load-bearing, scagliola is ideal for cladding structural elements in a building, and its comparative lightness allows it to be used in areas where stone and marble would be impractical. Its main limitations are two-fold: it cannot be used outdoors or in damp conditions; and because it is so labour-intensive, it is expensive – today often more so than marble, which has become industrialised at all stages of production.

19th century Scagliola Pedestal. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.