The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

Wilhelm Fistulator took over the family business on his father’s death in 1622. He had been apprenticed to Blasius in 1602 at the age of twelve and had worked alongside him ever since. When doubts were raised as to whether he was ready for such a responsible position, his application was supported by Heinrich Schön, the head of building works at the royal court. Schön stated that Wilhelm was already a master scagliolist (Meister Marmorier) who could work alone (i.e. unsupervised), and to a higher quality than even his father; furthermore, he had already stood in as head of the business in his father’s declining years.

Throughout his long career, Wilhelm worked exclusively for the Munich court, serving Maximilian (r. 1597-1651) and his son Ferdinand Maria (r.1651-1679). He pioneered the development of pictorial scagliola, creating naturalistic scenes and images in place of the simpler geometrical and stylised designs of his father. The quality and precision of his work is extraordinary. He was assisted by his wife Barbara and three of their six children, Franciscus, Ferdinand and Maria-Theresia.

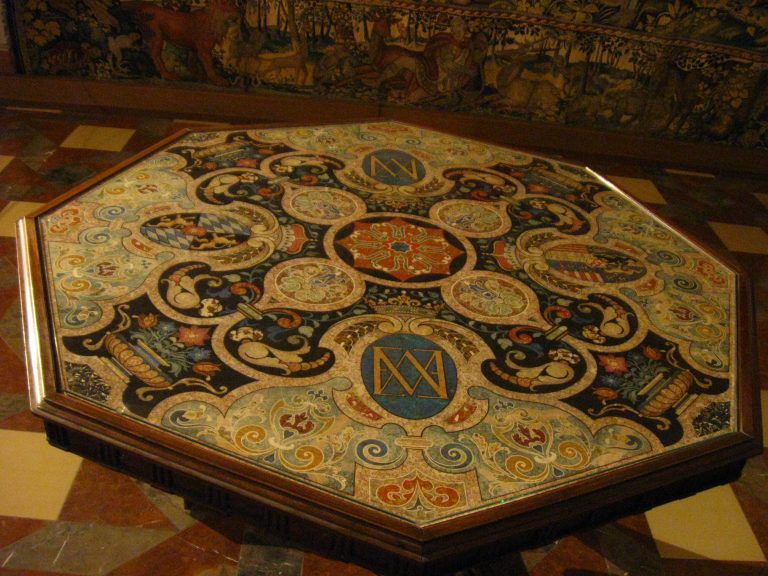

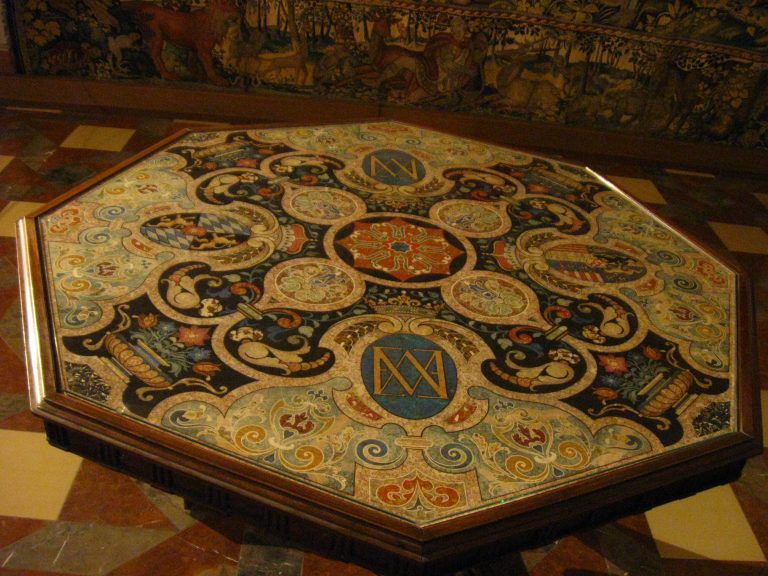

An Octagonal Table Top (c. 1623).

In the early 1620s Wilhelm made an octagonal scagliola tabletop which is displayed today in the Stone Rooms of the Munich Residence. Its style and design are similar to a late sixteenth century Florentine Pietre Dure tabletop, also in the Stone Rooms, which may well have served as a model.

The scagliola top has ornate flower vases on pedestals at four of the corners, with interspersed strapwork and stylised floral motifs. It specifically honours Maximilian’s new Electoral status, granted to him by the Emperor in 1623 after the Catholic victory over the Protestants at the Battle of the White Mountain. Between the flower vases there are four large ovals set in cartouches. Two of these bear the joint monograms of Maximilian and his wife Elisabeth of Lorraine, inlaid in gold lettering on a blue ground; the other two show their respective coats-of-arms. Maximilian’s coat-of-arms displays the newly-acquired Electoral orb in the centre (see footnotes below ref. dating).

The table is in very good condition, although the colours may have faded a little, particularly the blue of the Lapis Lazuli. The distinctive blue and white lozenges in the Wittelsbach coat-of-arms gave this costly and hard-to-obtain blue stone great significance for the family, and a report from 1609 states that the imitation of Lapis Lazuli by the Munich scagliolists was considered particularly impressive.

At this stage in his career, Wilhelm’s inlays are indistinguishable from those of his father; they are stylised and two dimensional in appearance, like those of the octagonal Pietre Dure tabletop mentioned above . There is however a hint of what was to come later in the depiction of the heraldic lions on the coats-of-arms. Unlike the flowers and vases, their yellow colours are subtly shaded, giving the animals a more three dimensional appearance.

The Schleißheim Panels (c. 1629)

At the end of the decade Wilhelm supplied scagliola panelling for two of the Trier rooms. A century later, in the 1720s, Elector Maximilian II Emanuel (r.1679-1726) had them moved to the New Palace of Schleißheim and installed in the Stucco Cabinet (formerly the Writing Cabinet), and the private chapel (Kammerkapelle), where they have survived to this day. They are clearly similar in style to those made by Blasius for the Reiche Kapelle. (Until the mid-twentieth century they were considered to be his work, but Dr. Neuman reported that when the panels were being removed for protection in 1943, the inscription 16WF29 was discovered on the back of one of the panels, implying that they were made by Wilhelm Fistulator in 1629).

The Schleißheim panels are important, not only because they allow us to appreciate Wilhelm’s work during this period; they also confirm the appearance of Blasius’s original Reiche Kapelle panels – now only visible in pre-war black and white photographs – and the accuracy of their reconstruction in the second half of the twentieth century.

The move towards pictorial scagliola.

In 1632, midway through the Thirty Years War, Bavaria was invaded by the Swedish army under King Gustavus Adolphus. While he was in Munich, the King was much impressed by a scagliola panel that hung over the chimney in the Residence’s Room of the Four Grey’s, the dining room reserved for the Emperor, between the Imperial Hall and the Stone Rooms; he wanted to take it away with him, and only refrained because he feared it would get damaged. The panel depicted a palace in which could be seen several different rooms, furnished with arches, columns, mouldings and other architectural features. An illusion of depth was created by the use of strong perspective. This was one of Wilhelm’s earliest pictorial pieces, made during the 1620s. Unfortunately it has not survived.

The move towards making pictures from scagliola had been given impetus by the Pietre Dure panels that the Castrucci family were making for the Emperor Rudolph in Prague since the late 1590s. At least one of these works, a gift from the Emperor to Duke Wilhelm or his son Maximilian, is known to have been in the royal collection; during his visit to Munich in 1611, Hainhoffer recorded seeing a Pietre Dure panel of ‘a beautiful landscape, created from colours made with natural stones inlaid and [put] together, as though it were a painting’.

If hardstone inlays could be used to create pictures, then why not scagliola? Technically speaking, it was no big jump from inlaying geometrical designs and stylised foliage to creating pictorial inlays. It would require of course some additional training in drawing and painting if these pictures were to work effectively; but we know from Maximilian’s letter to his Spanish cousin in 1609 that the young Wilhelm was already showing promise in painting.

In looking at these early pictorial representations in scagliola, we should bear in mind that the intention was to imitate Pietre Dure inlaid work, not painted pictures. Each scagliola inlay, however small, had to imitate a piece of hardstone or marble, just as it would in a mosaic. Despite this constraint, Wilhelm Fistulator’s ‘Perspectiven’ read extremely clearly, and the colour and scale of the different ‘marbles’ is finely balanced and appropriate to the subject matter depicted.

(Inevitably some fading has occurred; for instance many of the greens have ‘blued’ over the years. This can be blamed on the breakdown of unstable yellow pigments used in the making of green, a commonly occurring problem in pre-19th century scagliola.)

Wilhelm Fistulator’s panels for Reiche Kapelle.

The work for which Wilhelm is best remembered is the series of ten pictorial panels that he made for the Reiche Kapelle, whose scagliola walls had been installed by his father some twenty-five years earlier. The panels are based thematically, if not stylistically, on Dürer’s cycle of prints dedicated to the Life of the Virgin (c.1504). By the early 1600s Dürer’s reputation had achieved international status; the cycle was well known and likely to be found in all the major courts. Maximilian was a keen collector of Dürer’s work, and may have suggested the project himself.

Starting to the left of the entrance to the chapel and moving clockwise, the panels are situated as follows:

(Left hand wall)

(Right hand wall)

(Wall Panels 805mm x 715mm, Window Panels 815mm x 495m)

Michaela Liebhardt’s analysis of the Reiche Kapelle panels found direct links with Dürer, but also with the prints and paintings of the Dutch artist and architect Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527- c.1607), who published widely on architectural ornament and perspective.

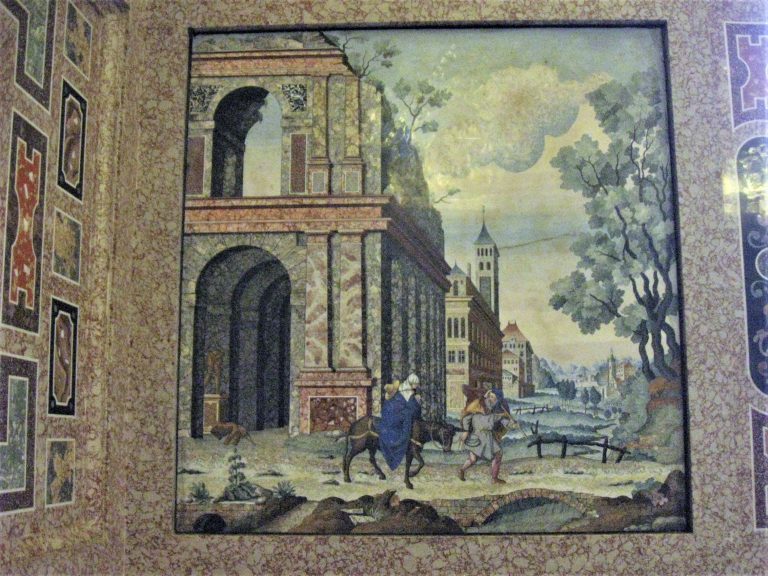

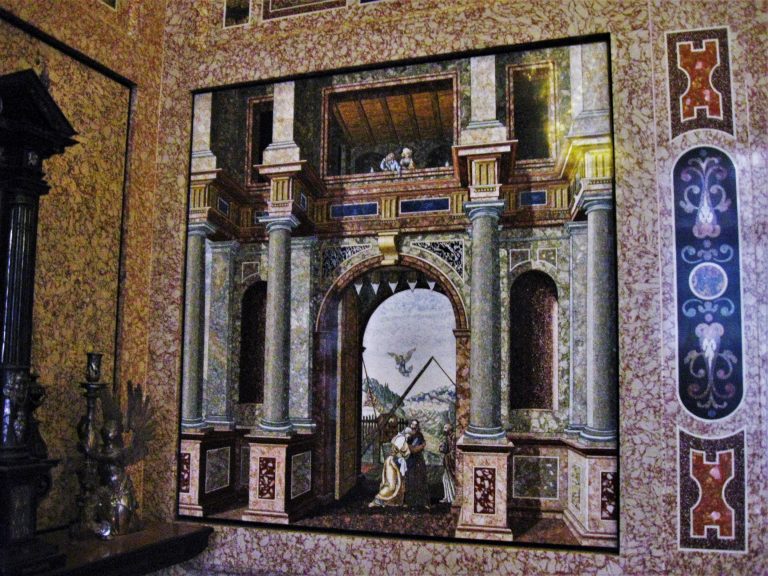

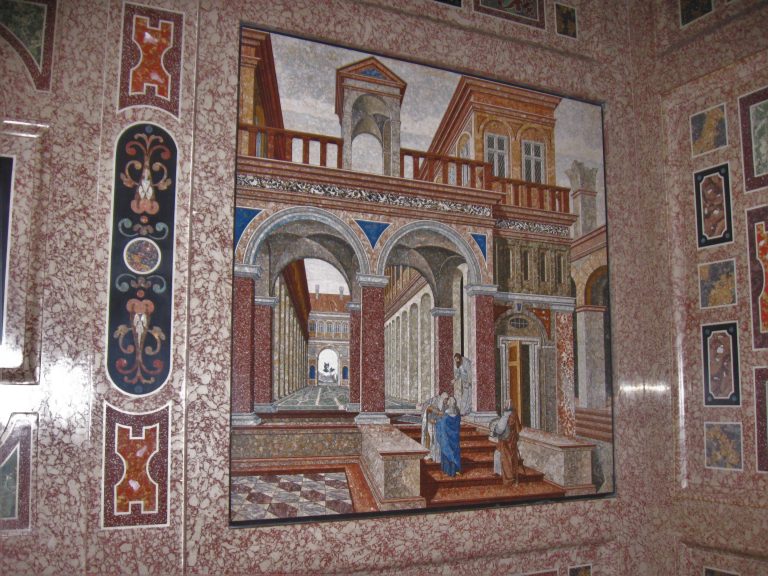

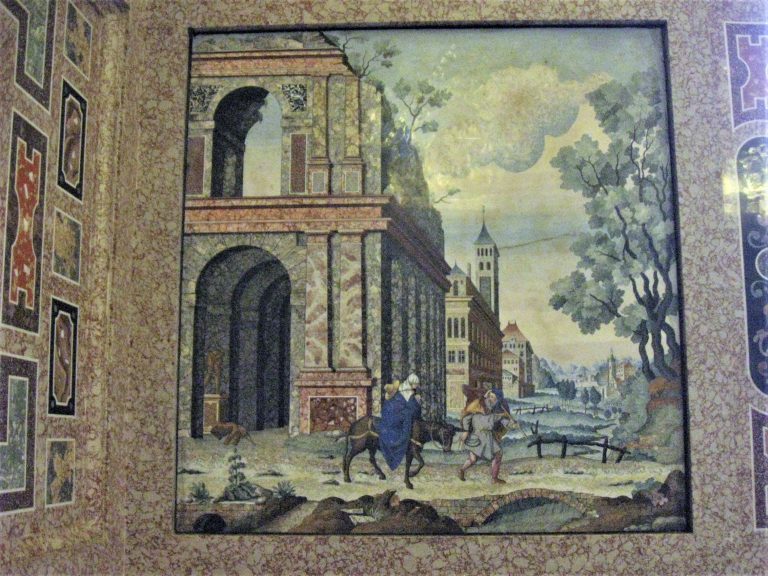

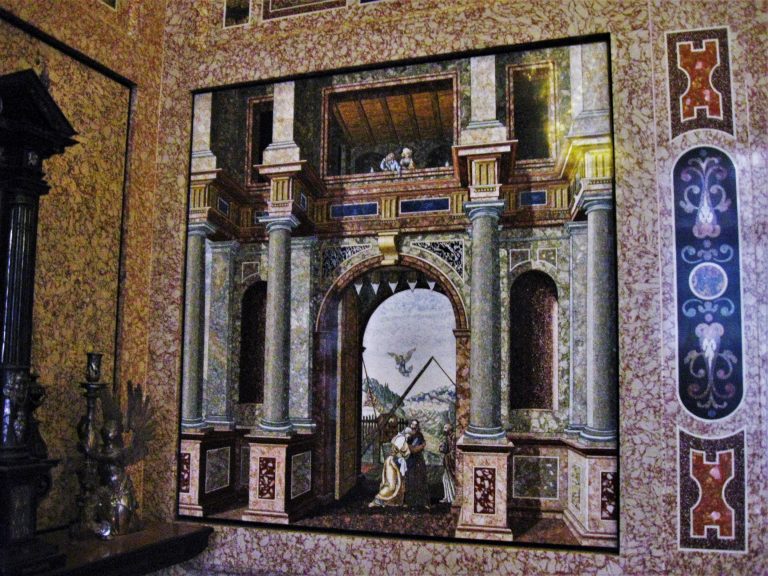

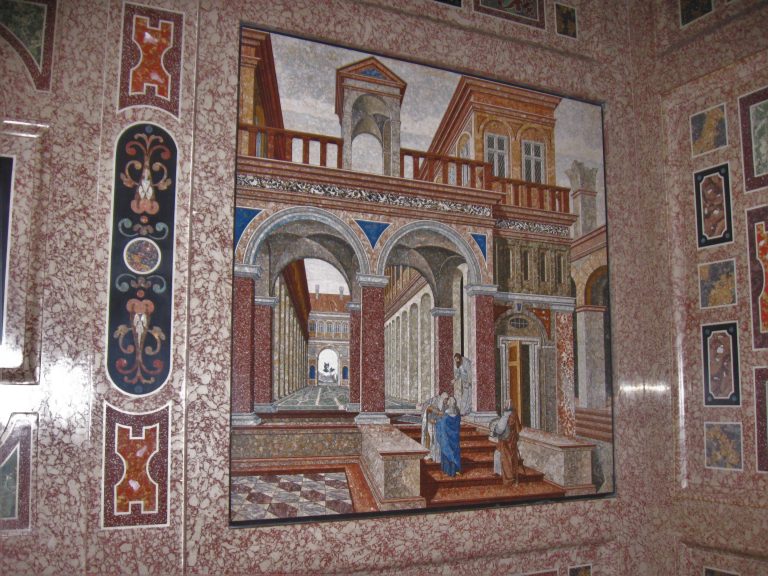

Wilhelm was particularly drawn to the depiction of grand architectural compositions in the style of de Vries; his inlaid panels feature triumphal archways – sometimes in ruins – and lofty hallways and loggias, sharply framed by cornices and mouldings. Walls are pierced with large openings which admit light and reveal other buildings or open countryside beyond. Receding colonnades and checkerboard floor tiles are set out in strict perspective, establishing depth and solidity.

There is an understandable appeal in depicting marble-clad buildings with imitation marble inlays; in a sense these scagliola pictures are miniature versions of the polychromatic marble interiors that were starting to appear in palaces and churches elsewhere in Europe.

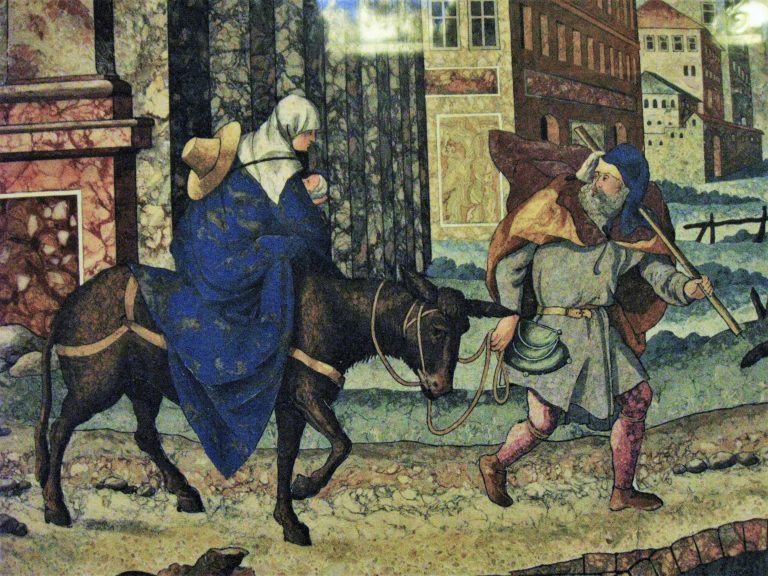

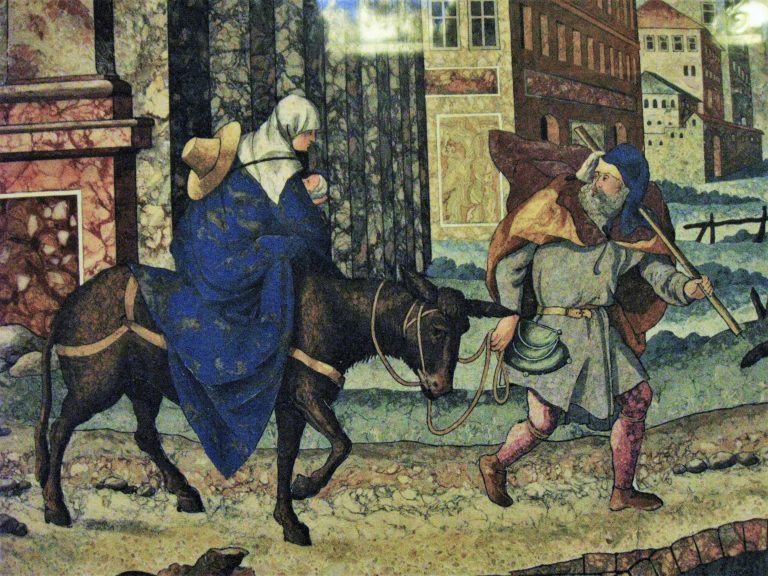

Drawn as he was to such geometrical precision, Wilhelm did not shy away from more naturalistic depictions. Despite their small scale the figures that inhabit his scenes are well-drawn and believable; their clothing and drapery suggest volume and their facial expressions are clear and life-like. The donkey carrying Mary and the Child in the ‘Flight into Egypt’ looks out at us with an expression full of meaning. (Facial expressions are rarely so successful in Pietre Dure work, where the hard contrasts in shape and colour make figures and faces seem static and awkward). Wilhelm’s landscapes, stylised in accordance with prevailing tastes, function effectively as receding backdrops, and still maintain the illusion of being formed from separate stone inlays. The same is true of plants and trees in the foreground.

As well as the ten scagliola scenes from the Life of Mary cycle, Wilhelm made eight panels depicting antique vases with flowers. They are installed in two sets of four on the right-hand wall of the Reiche Kapelle. The vases are round-bellied amphorae, decorated with acanthus leaves and cabled fluting, their handles formed from twisted serpents. The design, which dates back to Vitruvius, would have come from one of the many Netherlandish prints that were circulating throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.

The bodies of the vases are coloured in a brilliant blue Lapis Lazuli which stands out strongly against the black backgrounds, and is reflected in the blue of Mary’s robe that recurs in the pictures. The decorations and handles are golden. Each of the flower arrangements is different, and four of the panels have butterflies in their lower corners. The vases are shaded and appear three-dimensional; the flower arrangements seem flatter and more stylised in comparison.

All these panels were installed in 1632, after the Swedish army had left Bavaria. How long Wilhelm had been working on them is unknown. Maximilian was delighted and Wilhelm received a substantial pay rise (from 300 to 450 guilders per year); in return he had to agree to abstain completely from any work outside the royal household, and to refuse to teach his secrets to anyone, including his own children.

(Note: At the start of the Second World War all removable art works were taken from the Residence to safe-storage facilities outside Munich. Priority was given to anything flammable, and since plaster was considered non-flammable, orders were given to leave all the scagliola in place. I learnt anecdotally that an officer involved in the clearance operation decided that the scagliola pictures were too valuable to leave behind. He was able to remove six of them before being stopped by the authorities. It is thanks to him that those six originals survived the bombing at the end of the war. The other four panels and the flower vases are careful reconstructions made in the second half of the twentieth century).

Other work by Wilhelm Fistulator

In 1632 the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus invaded Bavaria and Duke Maximilian and his court retreated to safety in Austria, first to Salzburg and then to Brunau-am-Inn. The city of Munich paid a large indemnity to avoid ransack but this did not spare the Residence itself from being plundered. The military situation forced Gustavus to return north again, and he was killed at the Battle of Lützen in November of the same year. The Swedish threat remained however and Maximilian did not return to Munich until 1634.

Nevertheless, as early as June 1632 he was giving orders for reconstruction work to begin on the Munich Residence, and specific mention was made of the need for ‘…Wilhelm, so that imitation marble in Munich might be procured again...’ There are court records of disbursements made to Wilhelm in these years for travel expenses between Salzburg, Munich and Brunau, as well as additional payments for various Perspectiven and architectural features. Clearly he was considered one of Maximilian’s key craftsmen, and he was kept busy and well-paid. In 1636 he was able to buy a house in the Munich Kreuzviertel, an expensive area of the city favoured by clergy and monastics.

For the next twenty-five years Wilhelm Fistulator continued to produce inlaid pictorial scagliola for the royal court. This took the form of individual wall panels and tabletops, some of which have survived, and two complete rooms in the Munich Residence, which have not. There are examples of his work in the palace of Schleissheim (see above), the Bavarian National Museum in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In the Residence itself, apart from the ‘Life of Mary’ cycle, there are two architectural perspectives dating from the 1630s in the stair facia at the south end of the Antiquarium. Another perspective panel, larger and freer in style, was set into the base of the balustrading on the banqueting platform at the north end of the hall. This may have been made by Wilhelm’s wife Barbara or one of their children. A variation on this work, peopled with finely-dressed men and women, is held in the Kunstkammer at Trausnitz Castle.

The Papal Rooms.

The two rooms that Wilhelm decorated in scagliola are known as the Papal Rooms, in reference to Pope Pius VI who occupied them during a visit to Munich in 1782. The apartment is situated on the upper floor of the Grotto Courtyard (Grottenhof), and the work was carried out in the late 1630s and early 1640s for Maximilian’s second wife, Maria Anna of Austria.

The smaller of the rooms, known as the Herzkabinett (Heart Room), was decorated with scagliola panelling above the dado level. An inscription gave its date of completion as 1640. Eight large panels covered the upper walls, depicting architectural perspectives. The eight bays were separated by thin pilasters running from floor to ceiling. The original inlaid scagliola overmantel above the fireplace has survived with some repairs.

The second room, the Grottensaal, was named after the shell grotto on the west wall, and its scagliola went from floor to ceiling. The upper wall panels contained richly coloured floral decoration surrounding a central image, each one different (an antique vase, two dogs, a parrot etc.), inlaid in a black background in the style of contemporary Florentine mosaic. On closer inspection, small insects and birds could be seen partly hidden amongst the foliage. The lower wall panels were decorated with geometrical inlays, and once again thin pilasters ran from floor to ceiling.

Both these rooms were destroyed in the Second World War, but photos taken before give witness to the complexity and skill of the family’s achievements in this period. The court musician Pistorini praised them highly in 1644, and in 1771 the Italian antiquarian and connoisseur Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi described the scagliola as the finest example of the art he had ever seen (see note below for Bianconi’s views on contemporary Italian scagliola).

Family and Training.

Wilhelm sought permission to train two of his sons: Franciscus in 1641, followed by Ferdinand in 1651. The court agreed, accepting the need to preserve knowledge of the technique and provide an eventual successor to head the business. Needless to say, both sons were obliged to swear the oath of secrecy. Wilhelm also trained his wife Barbara, who he had married in 1621, and his daughter Maria-Theresia. The training of female members of the family appears to have been uncontested by the court; wives and daughters were unlikely to divulge the secrets of their husbands’ and fathers’ livelihoods. The women, frequently mentioned in the court records as Marmoratorin (female marbler), were never paid as much as the men and rarely received ex gratia payments. Wilhelm was also helped by an assistant named Michael Pfäffl, probably a labourer.

Maximilian I died in 1651, three years after the end of the Thirty Years War, and was succeeded by his son, Ferdinand Maria (r. 1651-1679). By then the finest scagliola interiors had been completed; money was short as a result of the war and there were no further significant commissions. Apart from a few individual panels and tabletops, and some door and chimney surrounds for the new country residence of Nymphenburg, the Munich scagliolists were occupied from this time on with maintenance, alterations and repairs.

In 1664 Ferdinand Fistulator wrote that his father was no longer engaged on any projects due to old age and infirmity, and in 1669 he died. Barbara was still active in the 1660’s, working on a refurbishment of the Herzkabinett and Grottenzimmer following the death in 1665 of the Dowager Electoress. She may also have been responsible for the scagliola work in the choir stalls and sacristy of St. Lawrence, Kempten, which was carried out in the late 1660s, (see Chapter 12). She died in 1674.

Wilhelm Fistulator was the first and undoubtedly one of the greatest pictorial scagliolists. Later scagliolists, mainly Italian, would use the material to imitate paintings, but Wilhelm always intended his work to be seen in the context of Pietre Dure inlay. In this he was following his father’s example and the wishes of his employer, Maximilian I of Bavaria.

References:

Michaela Liebhardt, Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987.

Note on dating tabletop: Liebhardt uses the appearance of the orb to demonstrate that the tabletop was made after Maximilian’s elevation to the electoral dignity in 1623. Whilst the dating may well be correct, the orb inlays could have been added at any time after the completion of the table – a simple task for a scagliola inlayer.

Note on Bianconi: the connoisseur went on to bemoan the fact that his countrymen had let go of an art that had once been exclusively Italian (in the second half of the 18th century this had become a common belief south of the Alps). He criticised contemporary Italian scagliola, with its cleverly drawn and assembled figures that had no use beyond their novelty value. One of Bianconi’s contacts in the Florentine art market, from whom he bought Old Masters for the Dresden Art Gallery, was Ignazio Hugford. He was the younger brother of Enrico Hugford, Abbot of Vallombrosa, considered by many – though not, it seems, Bianconi – to be the most accomplished scagliolist of the day.

Lorenz Seelig, Scagliola und Pietra Dura, Farbige Stein und Stückintarsien in Münchern Sclössern und Museen. Kunst & Antiquitaten 1/1987 p.29.

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.

Detail from a flat Scagliola Panel in the Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residenz (c. 1630). All the elements of the design are formed from scagliola copies of real marbles and hardstones.*

Octagonal Scagliola Table Top by Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1623). The Stone Rooms, Munich Residence.*

Top Left: 16th C. Florentine Pietre Dure Table Top, the likely model for Wilhelm Fistulator’s Scagliola table top. Other photos: details of Scagliola elements. (Click on images to enlarge). The Stone Rooms, Munich Residence.*

Scagliola panels made in the 1620s by Wilhlem Fistulator for the Munich Residence. They were moved to Schleißheim Castle in the 1720s to provide wall surfaces for the Stucco Kabinett (top) and the Kamerkapelle (bottom). The pierced ceiling of the Kamerkapelle has Régence style plasterwork and statues by JB Zimmermann. (Click on images to enlarge). Castle, Bavaria.*

Pietre Dure Landscape with Sacrifice of Isaac by Cosimo Castrucci c. 1600, Prague. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

The Flight into Egypt by Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

The Meeting at the Golden Gate by Wilhelm Fistulator (Reconstruction 2nd Half 20th Century). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

Architectural Caprice with Figures (1568) by Hans Vredman de Vries (1527-1607). Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. Image made available by Wikimedia Commons – Google Art Project.

The Visitation by Wilhelm Fistulator (Reconstruction 2nd Half 20th Century). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

Detail: The Flight into Egypt by Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

LHS. The Rest during the Flight into Egypt. RHS Christ in the Temple with the Elders and Christ and the Holy Family returning from the Temple Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). (Click on images to enlarge). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

One of eight Flower Vases based on Vitruvian Designs by Wilhelm Fistulator (Reconstruction 2nd Half 20th Century). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*.

Scagliola architectural perspective panels by Wilhem Fistualtor and family c. 1630s. Top: staircase facia at south-east end of the Antiquarium. Bottom: LHS north-west end of the Antiquarium RHS Kunstkammer, Trausnitz Castle, Landshut. (Click on images to enlarge). *

St. Francis receives the stigmata. Detail from a scagliola picture by Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1630s. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Scagliola overmantel in the Herzkabinett, original with repairs. Wilhelm Fistulator and family 1640. (Click on images to enlarge).*

Photograph of the Grottensaal taken before the 2nd World War.*

Pre-war photographs of scagliola panels in the Grottensaal by Wilhelm Fistulator and family. (Munich Residence c.1640. Click on images to enlarge).*

Detail from a scagliola panel (Joseph as a Carpenter) in the Reiche Kapelle. (Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1639)*

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze,

Wilhelm Fistulator took over the family business on his father’s death in 1622. He had been apprenticed to Blasius in 1602 at the age of twelve and had worked alongside him ever since. When doubts were raised as to whether he was ready for such a responsible position, his application was supported by Heinrich Schön, the head of building works at the royal court. Schön stated that Wilhelm was already a master scagliolist (Meister Marmorier) who could work alone (i.e. unsupervised), and to a higher quality than even his father; furthermore, he had already stood in as head of the business in his father’s declining years.

Detail from a flat Scagliola Panel in the Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residenz (c. 1630). All the elements of the design are formed from scagliola copies of real marbles and hardstones.*

Throughout his long career, Wilhelm worked exclusively for the Munich court, serving Maximilian (r. 1597-1651) and his son Ferdinand Maria (r.1651-1679). He pioneered the development of pictorial scagliola, creating naturalistic scenes and images in place of the simpler geometrical and stylised designs of his father. The quality and precision of his work is extraordinary. He was assisted by his wife Barbara and three of their six children, Franciscus, Ferdinand and Maria-Theresia.

An Octagonal Table Top (c. 1623).

In the early 1620s Wilhelm made an octagonal scagliola tabletop which is displayed today in the Stone Rooms of the Munich Residence. Its style and design are similar to a late sixteenth century Florentine Pietre Dure tabletop, also in the Stone Rooms, which may well have served as a model.

Octagonal Scagliola Table Top by Wilhelm Fistulator (c.1623). The Stone Rooms, Munich Residence.*

The scagliola top has ornate flower vases on pedestals at four of the corners, with interspersed strapwork and stylised floral motifs. It specifically honours Maximilian’s new Electoral status, granted to him by the Emperor in 1623 after the Catholic victory over the Protestants at the Battle of the White Mountain. Between the flower vases there are four large ovals set in cartouches. Two of these bear the joint monograms of Maximilian and his wife Elisabeth of Lorraine, inlaid in gold lettering on a blue ground; the other two show their respective coats-of-arms. Maximilian’s coat-of-arms displays the newly-acquired Electoral orb in the centre (see footnotes below ref. dating).

Top Left: 16th C. Florentine Pietre Dure Table Top, the likely model for Wilhelm Fistulator’s Scagliola table top. Other photos: details of Scagliola elements. (Click on images to enlarge). The Stone Rooms, Munich Residence.*

The table is in very good condition, although the colours may have faded a little, particularly the blue of the Lapis Lazuli. The distinctive blue and white lozenges in the Wittelsbach coat-of-arms gave this costly and hard-to-obtain blue stone great significance for the family, and a report from 1609 states that the imitation of Lapis Lazuli by the Munich scagliolists was considered particularly impressive.

At this stage in his career, Wilhelm’s inlays are indistinguishable from those of his father; they are stylised and two dimensional in appearance, like those of the octagonal Pietre Dure tabletop mentioned above . There is however a hint of what was to come later in the depiction of the heraldic lions on the coats-of-arms. Unlike the flowers and vases, their yellow colours are subtly shaded, giving the animals a more three dimensional appearance.

The Schleißheim Panels (c. 1629)

At the end of the decade Wilhelm supplied scagliola panelling for two of the Trier rooms. A century later, in the 1720s, Elector Maximilian II Emanuel (r.1679-1726) had them moved to the New Palace of Schleißheim and installed in the Stucco Cabinet (formerly the Writing Cabinet), and the private chapel (Kammerkapelle), where they have survived to this day. They are clearly similar in style to those made by Blasius for the Reiche Kapelle. (Until the mid-twentieth century they were considered to be his work, but Dr. Neuman reported that when the panels were being removed for protection in 1943, the inscription 16WF29 was discovered on the back of one of the panels, implying that they were made by Wilhelm Fistulator in 1629).

Scagliola panels made in the 1620s by Wilhlem Fistulator for the Munich Residence. They were moved to Schleißheim Castle in the 1720s to provide wall surfaces for the Stucco Kabinett (top) and the Kamerkapelle (bottom). The pierced ceiling of the Kamerkapelle has Régence style plasterwork and statues by JB Zimmermann. (Click on images to enlarge). Schleißheim Castle, Bavaria.*

The Schleißheim panels are important, not only because they allow us to appreciate Wilhelm’s work during this period; they also confirm the appearance of Blasius’s original Reiche Kapelle panels – now only visible in pre-war black and white photographs – and the accuracy of their reconstruction in the second half of the twentieth century.

The move towards pictorial scagliola.

In 1632, midway through the Thirty Years War, Bavaria was invaded by the Swedish army under King Gustavus Adolphus. While he was in Munich, the King was much impressed by a scagliola panel that hung over the chimney in the Residence’s Room of the Four Grey’s, the dining room reserved for the Emperor, between the Imperial Hall and the Stone Rooms; he wanted to take it away with him, and only refrained because he feared it would get damaged. The panel depicted a palace in which could be seen several different rooms, furnished with arches, columns, mouldings and other architectural features. An illusion of depth was created by the use of strong perspective. This was one of Wilhelm’s earliest pictorial pieces, made during the 1620s. Unfortunately it has not survived.

The move towards making pictures from scagliola had been given impetus by the Pietre Dure panels that the Castrucci family were making for the Emperor Rudolph in Prague since the late 1590s. At least one of these works, a gift from the Emperor to Duke Wilhelm or his son Maximilian, is known to have been in the royal collection; during his visit to Munich in 1611, Hainhoffer recorded seeing a Pietre Dure panel of ‘a beautiful landscape, created from colours made with natural stones inlaid and [put] together, as though it were a painting’.

Pietre Dure Landscape with Sacrifice of Isaac by Cosimo Castrucci c. 1600, Prague. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

If hardstone inlays could be used to create pictures, then why not scagliola? Technically speaking, it was no big jump from inlaying geometrical designs and stylised foliage to creating pictorial inlays. It would require of course some additional training in drawing and painting if these pictures were to work effectively; but we know from Maximilian’s letter to his Spanish cousin in 1609 that the young Wilhelm was already showing promise in painting.

In looking at these early pictorial representations in scagliola, we should bear in mind that the intention was to imitate Pietre Dure inlaid work, not painted pictures. Each scagliola inlay, however small, had to imitate a piece of hardstone or marble, just as it would in a mosaic. Despite this constraint, Wilhelm Fistulator’s ‘Perspectiven’ read extremely clearly, and the colour and scale of the different ‘marbles’ is finely balanced and appropriate to the subject matter depicted.

(Inevitably some fading has occurred; for instance many of the greens have ‘blued’ over the years. This can be blamed on the breakdown of unstable yellow pigments used in the making of green, a commonly occurring problem in pre-19th century scagliola.)

Wilhelm Fistulator’s panels for Reiche Kapelle.

The work for which Wilhelm is best remembered is the series of ten pictorial panels that he made for the Reiche Kapelle, whose scagliola walls had been installed by his father some twenty-five years earlier. The panels are based thematically, if not stylistically, on Dürer’s cycle of prints dedicated to the Life of the Virgin (c.1504). By the early 1600s Dürer’s reputation had achieved international status; the cycle was well known and likely to be found in all the major courts. Maximilian was a keen collector of Dürer’s work, and may have suggested the project himself.

The Flight into Egypt by Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

Starting to the left of the entrance to the chapel and moving clockwise, the panels are situated as follows:

(Left hand wall)

(Right hand wall)

(Wall Panels 805mm x 715mm, Window Panels 815mm x 495m)

The Meeting at the Golden Gate by Wilhelm Fistulator (Reconstruction 2nd Half 20th Century). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

Michaela Liebhardt’s analysis of the Reiche Kapelle panels found direct links with Dürer, but also with the prints and paintings of the Dutch artist and architect Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527- c.1607), who published widely on architectural ornament and perspective.

Wilhelm was particularly drawn to the depiction of grand architectural compositions in the style of de Vries; his inlaid panels feature triumphal archways – sometimes in ruins – and lofty hallways and loggias, sharply framed by cornices and mouldings. Walls are pierced with large openings which admit light and reveal other buildings or open countryside beyond. Receding colonnades and checkerboard floor tiles are set out in strict perspective, establishing depth and solidity.

Architectural Caprice with Figures (1568) by Hans Vredman de Vries (1527-1607). Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. Image made available by Wikimedia Commons – Google Art Project.

The Visitation by Wilhelm Fistulator (Reconstruction 2nd Half 20th Century). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

There is an understandable appeal in depicting marble-clad buildings with imitation marble inlays; in a sense these scagliola pictures are miniature versions of the polychromatic marble interiors that were starting to appear in palaces and churches elsewhere in Europe.

Drawn as he was to such geometrical precision, Wilhelm did not shy away from more naturalistic depictions. Despite their small scale the figures that inhabit his scenes are well-drawn and believable; their clothing and drapery suggest volume and their facial expressions are clear and life-like. The donkey carrying Mary and the Child in the ‘Flight into Egypt’ looks out at us with an expression full of meaning. (Facial expressions are rarely so successful in Pietre Dure work, where the hard contrasts in shape and colour make figures and faces seem static and awkward).

Detail: The Flight into Egypt by Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

Wilhelm’s landscapes, stylised in accordance with prevailing tastes, function effectively as receding backdrops, and still maintain the illusion of being formed from separate stone inlays. The same is true of plants and trees in the foreground.

LHS. The Rest during the Flight into Egypt. RHS Christ in the Temple with the Elders and Christ and the Holy Family returning from the Temple Wilhelm Fistulator (c. 1630). (Click on images to enlarge). Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*

As well as the ten scagliola scenes from the Life of Mary cycle, Wilhelm made eight panels depicting antique vases with flowers. They are installed in two sets of four on the right-hand wall of the Reiche Kapelle. The vases are round-bellied amphorae, decorated with acanthus leaves and cabled fluting, their handles formed from twisted serpents. The design, which dates back to Vitruvius, would have come from one of the many Netherlandish prints that were circulating throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.

One of eight Vitruvian Flower Vases by Wilhelm Fistulator. (Reconstruction 2nd half 20th Century). The Reiche Kapelle, Munich Residence.*.

The bodies of the vases are coloured in a brilliant blue Lapis Lazuli which stands out strongly against the black backgrounds, and is reflected in the blue of Mary’s robe that recurs in the pictures. The decorations and handles are golden. Each of the flower arrangements is different, and four of the panels have butterflies in their lower corners. The vases are shaded and appear three-dimensional; the flower arrangements seem flatter and more stylised in comparison.

All these panels were installed in 1632, after the Swedish army had left Bavaria. How long Wilhelm had been working on them is unknown. Maximilian was delighted and Wilhelm received a substantial pay rise (from 300 to 450 guilders per year); in return he had to agree to abstain completely from any work outside the royal household, and to refuse to teach his secrets to anyone, including his own children.

(Note: At the start of the Second World War all removable art works were taken from the Residence to safe-storage facilities outside Munich. Priority was given to anything flammable, and since plaster was considered non-flammable, orders were given to leave all the scagliola in place. I learnt anecdotally that an officer involved in the clearance operation decided that the scagliola pictures were too valuable to leave behind. He was able to remove six of them before being stopped by the authorities. It is thanks to him that those six originals survived the bombing at the end of the war. The other four panels and the flower vases are careful reconstructions made in the second half of the twentieth century).

Other work by Wilhelm Fistulator

In 1632 the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus invaded Bavaria and Duke Maximilian and his court retreated to safety in Austria, first to Salzburg and then to Brunau-am-Inn. The city of Munich paid a large indemnity to avoid ransack but this did not spare the Residence itself from being plundered. The military situation forced Gustavus to return north again, and he was killed at the Battle of Lützen in November of the same year. The Swedish threat remained however and Maximilian did not return to Munich until 1634.

Nevertheless, as early as June 1632 he was giving orders for reconstruction work to begin on the Munich Residence, and specific mention was made of the need for ‘…Wilhelm, so that imitation marble in Munich might be procured again…’ There are court records of disbursements made to Wilhelm in these years for travel expenses between Salzburg, Munich and Brunau, as well as additional payments for various Perspectiven and architectural features. Clearly he was considered one of Maximilian’s key craftsmen, and he was kept busy and well-paid. In 1636 he was able to buy a house in the Munich Kreuzviertel, an expensive area of the city favoured by clergy and monastics.

For the next twenty-five years Wilhelm Fistulator continued to produce inlaid pictorial scagliola for the royal court. This took the form of individual wall panels and tabletops, some of which have survived, and two complete rooms in the Munich Residence, which have not. There are examples of his work in the palace of Schleissheim (see above), the Bavarian National Museum in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

St. Francis receives the stigmata. Detail from a scagliola picture by Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1630s. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In the Residence itself, apart from the ‘Life of Mary’ cycle, there are two architectural perspectives dating from the 1630s in the stair facia at the south end of the Antiquarium. Another perspective panel, larger and freer in style, was set into the base of the balustrading on the banqueting platform at the north end of the hall. This may have been made by Wilhelm’s wife Barbara or one of their children. A variation on this work, peopled with finely-dressed men and women, is held in the Kunstkammer at Trausnitz Castle.

Scagliola architectural perspective panels by Wilhem Fistualtor and family c. 1630s. Top: staircase facia at south-east end of the Antiquarium. Bottom: LHS north-west end of the Antiquarium RHS Kunstkammer, Trausnitz Castle, Landshut. (Click on images to enlarge). *

The Papal Rooms.

The two rooms that Wilhelm decorated in scagliola are known as the Papal Rooms, in reference to Pope Pius VI who occupied them during a visit to Munich in 1782. The apartment is situated on the upper floor of the Grotto Courtyard (Grottenhof), and the work was carried out in the late 1630s and early 1640s for Maximilian’s second wife, Maria Anna of Austria.

The smaller of the rooms, known as the Herzkabinett (Heart Room), was decorated with scagliola panelling above the dado level. An inscription gave its date of completion as 1640. Eight large panels covered the upper walls, depicting architectural perspectives. The eight bays were separated by thin pilasters running from floor to ceiling. The original inlaid scagliola overmantel above the fireplace has survived with some repairs.

Scagliola overmantel in the Herzkabinett, original with repairs. Wilhelm Fistulator and family 1640. (Click on images to enlarge).*

The second room, the Grottensaal, was named after the shell grotto on the west wall, and its scagliola went from floor to ceiling. The upper wall panels contained richly coloured floral decoration surrounding a central image, each one different (an antique vase, two dogs, a parrot etc.), inlaid in a black background in the style of contemporary Florentine mosaic. On closer inspection, small insects and birds could be seen partly hidden amongst the foliage. The lower wall panels were decorated with geometrical inlays, and once again thin pilasters ran from floor to ceiling.

Photograph of the Grottensaal taken before the 2nd World War.*

Both these rooms were destroyed in the Second World War, but photos taken before give witness to the complexity and skill of the family’s achievements in this period. The court musician Pistorini praised them highly in 1644, and in 1771 the Italian antiquarian and connoisseur Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi described the scagliola as the finest example of the art he had ever seen (see note below for Bianconi’s views on contemporary Italian scagliola).

Pre-war photographs of scagliola panels in the Grottensaal by Wilhelm Fistulator and family (Munich Residence c.1640. Click on images to enlarge).*

Family and Training.

Wilhelm sought permission to train two of his sons: Franciscus in 1641, followed by Ferdinand in 1651. The court agreed, accepting the need to preserve knowledge of the technique and provide an eventual successor to head the business. Needless to say, both sons were obliged to swear the oath of secrecy. Wilhelm also trained his wife Barbara, who he had married in 1621, and his daughter Maria-Theresia. The training of female members of the family appears to have been uncontested by the court; wives and daughters were unlikely to divulge the secrets of their husbands’ and fathers’ livelihoods. The women, frequently mentioned in the court records as Marmoratorin (female marbler), were never paid as much as the men and rarely received ex gratia payments. Wilhelm was also helped by an assistant named Michael Pfäffl, probably a labourer.

Maximilian I died in 1651, three years after the end of the Thirty Years War, and was succeeded by his son, Ferdinand Maria (r. 1651-1679). By then the finest scagliola interiors had been completed; money was short as a result of the war and there were no further significant commissions. Apart from a few individual panels and tabletops, and some door and chimney surrounds for the new country residence of Nymphenburg, the Munich scagliolists were occupied from this time on with maintenance, alterations and repairs.

In 1664 Ferdinand Fistulator wrote that his father was no longer engaged on any projects due to old age and infirmity, and in 1669 he died. Barbara was still active in the 1660’s, working on a refurbishment of the Herzkabinett and Grottenzimmer following the death in 1665 of the Dowager Electoress. She may also have been responsible for the scagliola work in the choir stalls and sacristy of St. Lawrence, Kempten, which was carried out in the late 1660s, (see Chapter 12). She died in 1674.

Wilhelm Fistulator was the first and undoubtedly one of the greatest pictorial scagliolists. Later scagliolists, mainly Italian, would use the material to imitate paintings, but Wilhelm always intended his work to be seen in the context of Pietre Dure inlay. In this he was following his father’s example and the wishes of his employer, Maximilian I of Bavaria.

Detail from a scagliola panel (Joseph as a Carpenter) in the Reiche Kapelle. (Wilhelm Fistulator c. 1639)*

* © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, www.schloesser.bayern.de

Photos by Richard Feroze.

References:

Michaela Liebhardt, Die Münchener Scagliolaarbeiten des 17. Und 18. Jahrhunderts: Inaugural Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades de Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München – Aus München 1987.

Note on dating tabletop: Liebhardt uses the appearance of the orb to demonstrate that the tabletop was made after Maximilian’s elevation to the electoral dignity in 1623. Whilst the dating may well be correct, the orb inlays could have been added at any time after the completion of the table – a simple task for a scagliola inlayer.

Note on Bianconi: the connoisseur went on to bemoan the fact that his countrymen had let go of an art that had once been exclusively Italian (in the second half of the 18th century this had become a common belief south of the Alps). He criticised contemporary Italian scagliola, with its cleverly drawn and assembled figures that had no use beyond their novelty value. One of Bianconi’s contacts in the Florentine art market, from whom he bought Old Masters for the Dresden Art Gallery, was Ignazio Hugford. He was the younger brother of Enrico Hugford, Abbot of Vallombrosa, considered by many – though not, it seems, Bianconi – to be the most accomplished scagliolist of the day.

Lorenz Seelig, Scagliola und Pietra Dura, Farbige Stein und Stückintarsien in Münchern Sclössern und Museen. Kunst & Antiquitaten 1/1987 p.29.

Neumann, E: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in’ Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 pp. 75-158.