Chapter 19. The Carpi Masters - Second Generation

Giovan Marco Barzelli (Carpi 1637-1693)

Towards the end of his life Giovanni Gavignani began to use small amounts of colour in his paliotti, mainly in the floral work surrounding the central images. The tones were pale and delicate, and this subtle colouring became the hallmark of one his most talented pupils, Giovan Marco Barzelli.

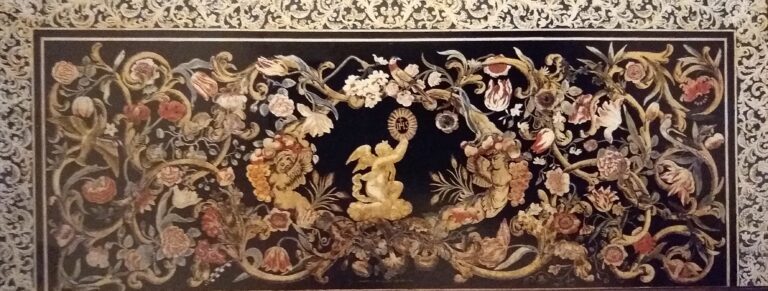

An altar front made by Giovanni Gavignani towards the end of his life in the commune of Budrione to the north of Carpi

The move away from the austerity of black and white scagliola towards colour and greater exuberance was a response to the baroque style of decoration that was already becoming well established in Rome, but had been slow to reach provincial Emilia. A more direct influence came from the work of the Florentine marble mosaicists, whose ornamental motifs and brilliantly coloured floral inlays had reached northern Italy, largely through the activities of the Corbarelli family.* Pietro Paolo Corbarelli had moved to Padua in the 1640s. His numerous sons and grandsons found work in other cities in the Veneto and Lombardy, and in 1681 Benedetto Corbarelli was asked by the Duke of Modena to establish and direct a Pietre Dure workshop in Modena.

* Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997 pp. 103-4

The high altar in the Church of Santa Corona, Vicenza. The front, sides and back are clad in Pietre Dure panels produced by the Corbarelli workshop over a period of nearly 20 years. (Vicenza, Veneto 1669-1685).

The production of Florentine mosaics on their own doorstep did not go unnoticed by the Carpi scagliolists. They continued to use the black and white technique for pictures and small decorative borders, but now colour flowed back into their work, adding to its inventiveness and richness.

***

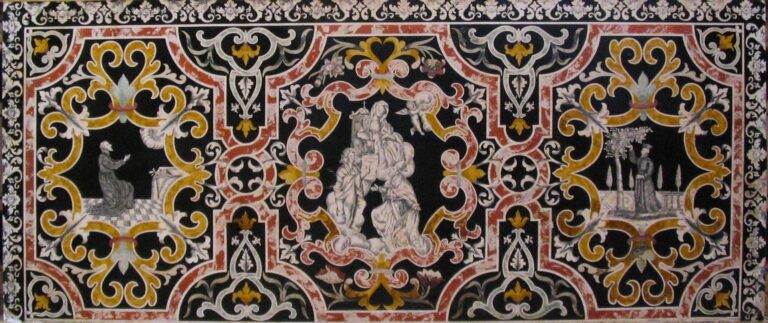

In his early years Barzelli had copied his master, producing black and white altar fronts in the traditional tripartite form. He achieved considerable expressiveness in his figure work, as can be seen in his rendering of the Madonna of the Rosary (probably taken from a print by Lorenzo Loli) in the church of San Pietro of Limidi. (There are further signed examples in the parish church of Gargallo and San Giacomo Roncole, Mirandola).

The Madonna of the Rosary. Central image of an altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli. (Church of San Pietro, Limidi, 2nd half 17th C.)

In the 1680’s he began to produce a new style of altar front, several examples of which have survived. The design features a wide outer border running continuously around a single central field. The border is filled with a naturalistic arrangement of flowers and foliage in full colour, in contrast to the black and white stylised acanthus decoration of his earlier work; the colours (as in Gavignani’s late work), are restrained and subtle, though the jet black background considerably intensifies their effect. A similar floral band frames a central black and white image of a religious figure or event.

The earliest of these pieces (signed and dated 1681) is in the abbey church of San Pietro in Modena. Apart from the central image, the Conversion of St. Paul framed within a wreath of flowers and foliage, the rest of the inner field is black.

Altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli in the Abbey Church of San Pietro in Modena (signed and dated 1681). The central image depicts the conversion of St. Paul.

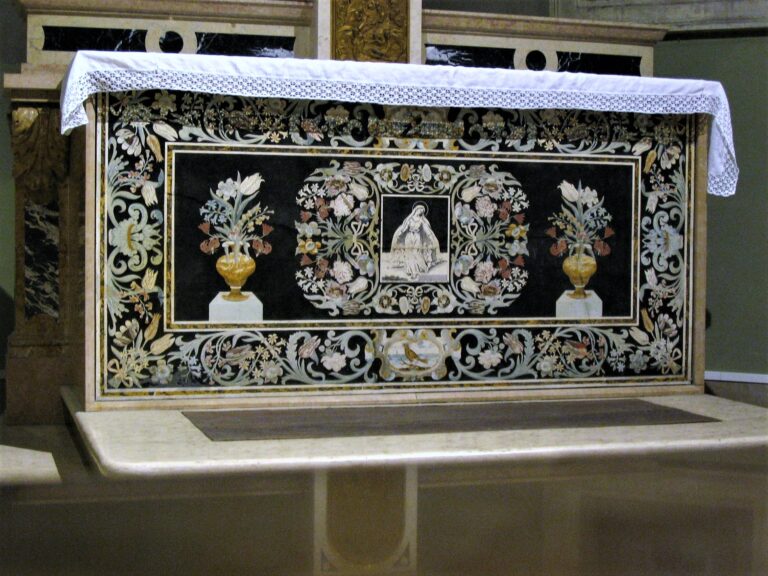

In a later example Barzelli added flower vases on either side of the image, harking back to the traditional tripartite form. These two works have identical floral borders and framing of the central images .

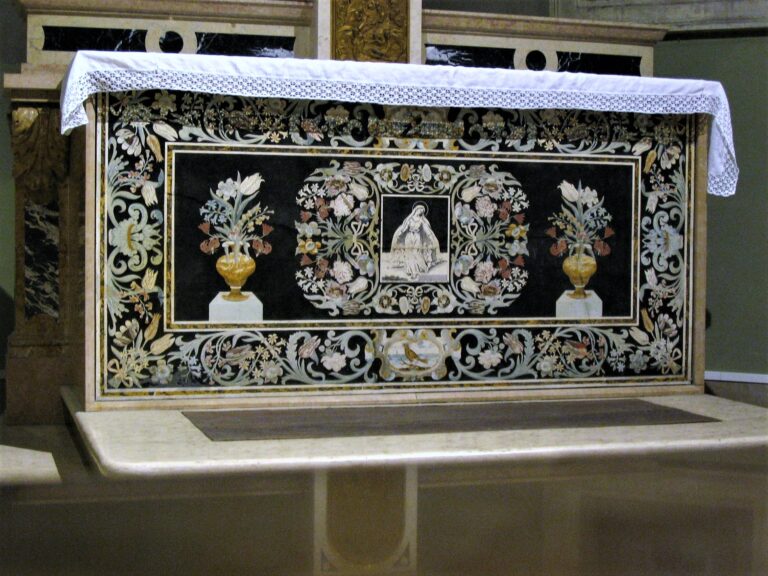

Altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli in the Abbey Church of San Pietro in Modena (signed and dated 1683). The central image depicts the Madonna of Mercy.

Further works in this style can be seen in Reggio Emilia (Church of San Georgio) and Correggio (Church of San Giuseppe Calasanzio).

Barzelli’s use of colour gives an early example of the way that scagliola could imitate inlaid Pietre Dure, but with a softer range of tones. The brilliance of inlaid marble and hardstone, which can draw the eye to the materials as much as to the design, is exchanged for a more harmonious effect, where all the colours are aligned and nothing jumps out at the viewer – one of the special qualities of good scagliola.

Gasparo Griffoni (Carpi 1640-1698)

Gasparo was the son of Annibale Griffoni, with whom he trained alongside Barzelli. He became a priest, and as well as making scagliola, was the choir master of Carpi Cathedral. He was responsible for training three of the most accomplished scagliolists of the late seventeenth century, Marco Mazelli, Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa (see below Chapter 20).

He made several pieces of architectural scagliola, including the impressive ciborium (where the communion Host is stored) for the church of Santa Maria della Neve in Motta di Cavezzo. This monument, which stands two and a half metres high, is in the form of an eight-sided domed temple; it has eight engaged Corinthian columns set on pedestals, and a moulded plinth. The scagliola is a mixture of marbled pinks, reds and greys, with black column shafts and border strips; the upper section and dome are inlaid with geometrically shaped panels typical of Roman Pietre Dure.

Scagliola Ciborium by Gaspari Griffoni dated 1672 (Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo)

Gasparo Griffoni produced several altar fronts, and like Barzelli he also used a mixture of black and white and colour. In the same church of Santa Maria delle Neve there are three altar fronts ascribed to him. Two of them are entirely black and white; the third has pale colours in the two vases of flowers which sit on each side of a central black and white image of the Crucifixion. In place of Barzelli’s striking floral borders, Gasparo used the traditional lace-work and candelabra decorations for the top and side edges of his altar fronts. The chiaroscuro work is finely executed, giving a satisfying solidity to the images.

Scagliola Paliotto with black and white central image of the crucifixion and two flanking flower vases with faded colouring by Gasparo Griffoni. (Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo c. 1670s).

Black and white scagliola image of St. Anthony of Padua and the Christ child, by Gasparo Griffoni. (Altar detail in the church of Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo c. 1670s)

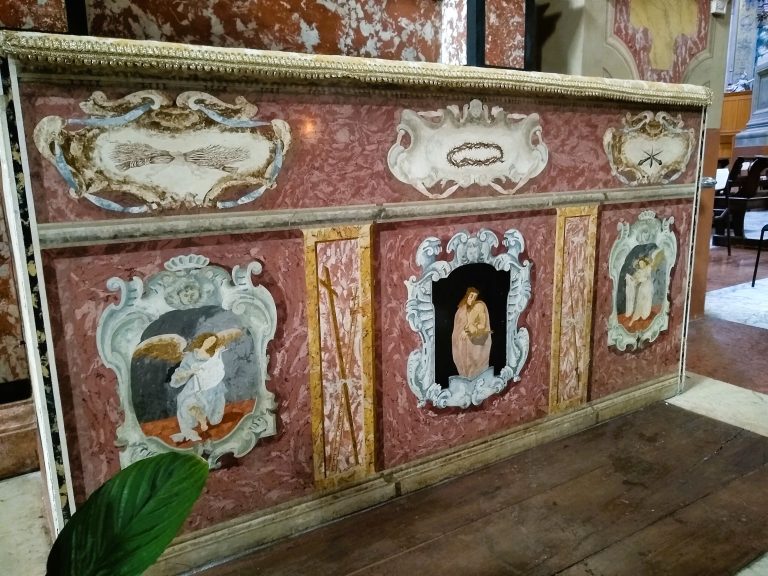

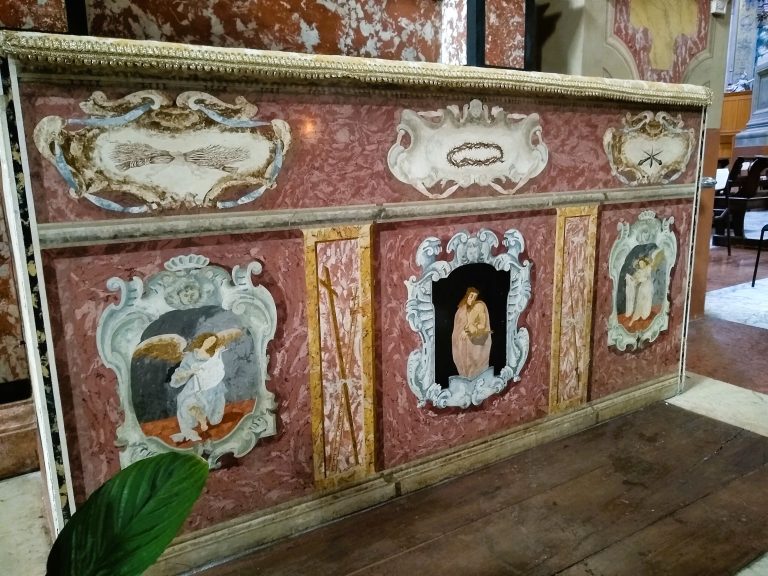

Paliotto by Gasparo Griffoni in Carpi Cathedral with pictorial scagliola images of Christ and two angels.

A paliotto in Carpi Cathedral by Gasparo Griffoni (doc.1670) has a main section which is split into three panels by two thin pilasters. Each panel is inlaid with a baroque cartouche which frames an image, an Ecce Homo in the centre, and single angels at the two sides. The images, which are rendered in colour, are an early attempt by a Carpigian to produce paintings in scagliola; the results are somewhat crude, but the work is worthy of mention for its innovation.

Marco Mazelli (Carpi 1640-Ferrara last doc. 1713)

Although from the second generation of Carpigian scagliolists, Marco Mazelli’s work belongs stylistically to both the second and third. This is explained by his long working life; he was seventy-three when he made his last documented altar front. Mazelli used the subtle colours favoured by the Carpigian scagliolists of his generation, set off against a plain black background, and bordered on the top edge and sides with strips of black and white lacework. The design of his early altar pieces has a tripartite organisation, but the stylised candelabra are replaced by imitation marble bandwork surrounding the three main panels. These contain a variety of images: religious figures and events executed in black and white; multi-coloured images of parrots on branches and bunches of flowers; panels of imitation antique marble, including Giallo Antico, Verde Antico and Porphyry.

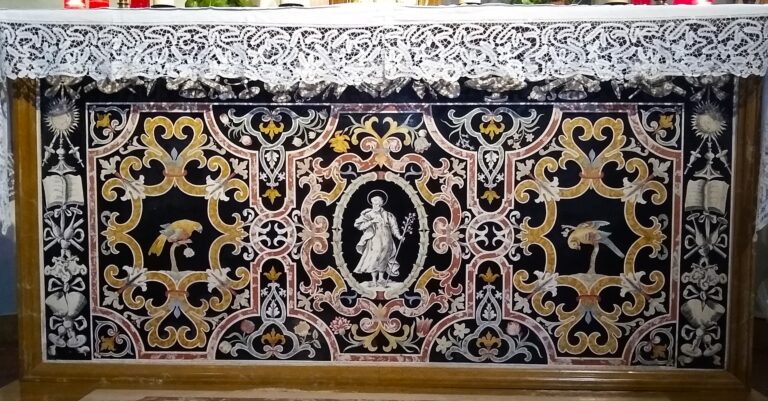

Scagliola Paliotto with central image depicting St. Peter flanked by parrots. (Abbey of San Pietro, Modena, by Marco Mazelli. 1680’s/90’s).

Mazelli also used the same stencils on different altar pieces, changing the images to give variation. His output was prolific, and there are works from this period of his life in several of the Emilian churches.* In Modena there are examples in the abbey church of San Pietro, the Chiesa di San Vincenzo, the Chiesa del Voto and the Chiesa della Pomposa.

Scagliola paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Chiesa of San Vincenzo (c. 1680’s). Note the identical design of the strapwork in these two works, showing the use of the same stencil and the same colours.

Detail of a parrot surrounded by similar foliage and strapwork, from a paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Chiesa del Voto, Modena.

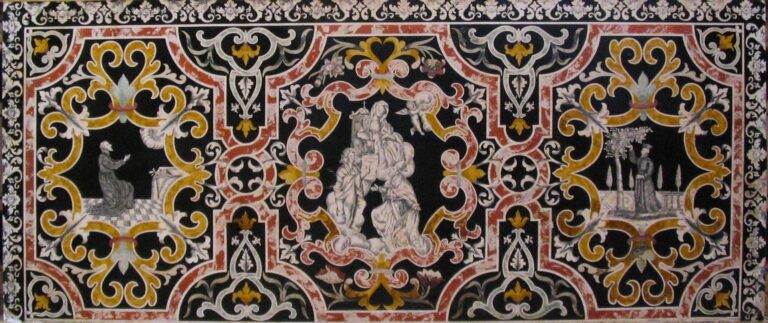

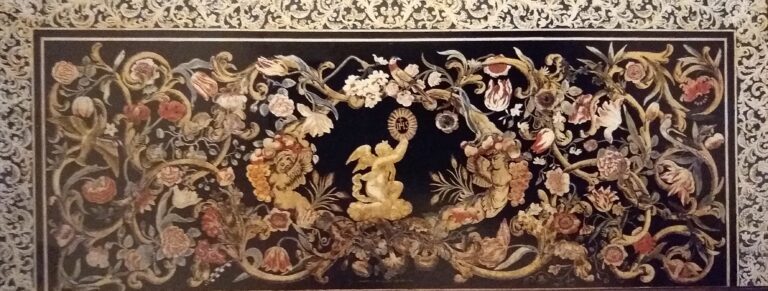

At the end of the century he developed a completely new approach. The earliest known example is an altar front he made for the private chapel in the castle of Spezzano di Fiorano (nr. Modena) signed and dated 1699. A similar work taken from the same stencil, originally in the parish church of Sant’Agostino in Modena, can be seen in the city museum (where it was moved in the nineteenth century). In these altar pieces the tripartite scheme has completely disappeared, and the entire picture field is now covered with thick, sinuous foliage containing birds, flowers, fruit, cornucopia and grotesques. Hatching lines are reduced to a minimum, and colour itself is used to create shading and detail.

Scagliola paliotto by Marco Mazelli, created from an identical stencil used for an altar in the private chapel of the Castello di Fiorano near Modena and dated 1699. It was moved to the Civic Museum of Modena in the 19th century.

Pietre Dure elements are still evident in these early baroque designs, but the intention is much closer to painting, and the degree of pictorial realism has gone beyond that achievable with inlaid stone. On the other hand, unlike real paintings these altar slabs could be polished to take on a marble-like appearance, giving them value not only as precious works of art, but also of illusion.

At the turn of the century Mazelli moved to the Duchy of Parma, possibly to avoid competition from Pozzuoli and Massa, younger scagliolists with whom he had worked under Gasparo Griffoni, and who were now active in their own right in the Duchy of Modena (see next Chapter). While there, he supplied a magnificent set of four pairs of altar fronts to the Sanctuary of the Madonna of the Rosary at Fontanellato. They are all in his later style, signed and dated 1701; as in earlier work, identical stencils were used for the decorative elements of each pair, with different images placed within the various cartouches. This was a significant commission, perhaps the largest yet for a single church, and implies that Mazelli had access to several skilled assistants.

One of eight altar fronts by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary Church of the Madonna of the Rosary, Fontanellato, Parma (signed and dated 1701).

Details from two different altar fronts by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary Church of the Madonna of the Rosary, Palma (signed and dated 1701)

Shortly after the completion of this work, he moved east to the Papal States, settling in Ferrara. He left works in Ferrara and Ravenna, and his last known altar piece, signed and dated 1713, is in the church of San Paolo in Ferrara.**

* Motta di Cavezzo, Camposanto, Sassuolo, Marzaglia et al. See Manni pp.82-109

** Traditinally Mazelli is credited with introducing the technique to Montefeltro and Le Marche. This is overstated, on the grounds that there is scagliola work in the region which predates his arrival; but nevertheless, the presence of such a skilfull and long-lived scagliolist must have had a significant influence on the spread and popularity of the material.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997

Chapter 19. The Carpi Masters - Second Generation

Giovan Marco Barzelli (Carpi 1637-1693)

Towards the end of his life Giovanni Gavignani began to use small amounts of colour in his paliotti, mainly in the floral work surrounding the central images. The tones were pale and delicate, and this subtle colouring became the hallmark of one his most talented pupils, Giovan Marco Barzelli.

An altar front made by Giovanni Gavignani towards the end of his life in the commune of Budrione to the north of Carpi

The move away from the austerity of black and white scagliola towards colour and greater exuberance was a response to the baroque style of decoration that was already becoming well established in Rome, but had been slow to reach provincial Emilia. A more direct influence came from the work of the Florentine marble mosaicists, whose ornamental motifs and brilliantly coloured floral inlays had reached northern Italy, largely through the activities of the Corbarelli family.* Pietro Paolo Corbarelli had moved to Padua in the 1640s. His numerous sons and grandsons found work in other cities in the Veneto and Lombardy, and in 1681 Benedetto Corbarelli was asked by the Duke of Modena to establish and direct a Pietre Dure workshop in Modena.

* Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997 pp. 103-4

The high altar in the Church of Santa Corona, Vicenza. The front, sides and back are clad in Pietre Dure panels produced by the Corbarelli workshop over a period of nearly 20 years. (Vicenza, Veneto 1669-1685).

The production of Florentine mosaics on their own doorstep did not go unnoticed by the Carpi scagliolists. They continued to use the black and white technique for pictures and small decorative borders, but now colour flowed back into their work, adding to its inventiveness and richness.

***

In his early years Barzelli had copied his master, producing black and white altar fronts in the traditional tripartite form. He achieved considerable expressiveness in his figure work, as can be seen in his rendering of the Madonna of the Rosary (probably taken from a print by Lorenzo Loli) in the church of San Pietro of Limidi. (There are further signed examples in the parish church of Gargallo and San Giacomo Roncole, Mirandola).

The Madonna of the Rosary. Central image of an altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli. (Church of San Pietro, Limidi, 2nd half 17th C.)

In the 1680’s he began to produce a new style of altar front, several examples of which have survived. The design features a wide outer border running continuously around a single central field. The border is filled with a naturalistic arrangement of flowers and foliage in full colour, in contrast to the black and white stylised acanthus decoration of his earlier work; the colours (as in Gavignani’s late work), are restrained and subtle, though the jet black background considerably intensifies their effect. A similar floral band frames a central black and white image of a religious figure or event.

The earliest of these pieces (signed and dated 1681) is in the abbey church of San Pietro in Modena. Apart from the central image, the Conversion of St. Paul framed within a wreath of flowers and foliage, the rest of the inner field is black.

Altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli in the Abbey Church of San Pietro in Modena (signed and dated 1683). The central image depicts the Madonna of Mercy.

In a later example Barzelli added flower vases on either side of the image, harking back to the traditional tripartite form. These two works have identical floral borders and framing of the central images .

Altar front by Giovan Marco Barzelli in the Abbey Church of San Pietro in Modena (signed and dated 1681). The central image depicts the conversion of St. Paul.

Further works in this style can be seen in Reggio Emilia (Church of San Georgio) and Correggio (Church of San Giuseppe Calasanzio).

Barzelli’s use of colour gives an early example of the way that scagliola could imitate inlaid Pietre Dure, but with a softer range of tones. The brilliance of inlaid marble and hardstone, which can draw the eye to the materials as much as to the design, is exchanged for a more harmonious effect, where all the colours are aligned and nothing jumps out at the viewer – one of the special qualities of good scagliola.

Gasparo Griffoni (Carpi 1640-1698)

Gasparo was the son of Annibale Griffoni, with whom he trained alongside Barzelli. He became a priest, and as well as making scagliola, was the choir master of Carpi Cathedral. He was responsible for training three of the most accomplished scagliolists of the late seventeenth century, Marco Mazelli, Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa (see below Chapter 20).

He made several pieces of architectural scagliola, including the impressive ciborium (where the communion Host is stored) for the church of Santa Maria della Neve in Motta di Cavezzo. This monument, which stands two and a half metres high, is in the form of an eight-sided domed temple; it has eight engaged Corinthian columns set on pedestals, and a moulded plinth. The scagliola is a mixture of marbled pinks, reds and greys, with black column shafts and border strips; the upper section and dome are inlaid with geometrically shaped panels typical of Roman Pietre Dure.

Scagliola Ciborium by Gaspari Griffoni dated 1672 (Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo)

Gasparo Griffoni produced several altar fronts, and like Barzelli he also used a mixture of black and white and colour. In the same church of Santa Maria delle Neve there are three altar fronts ascribed to him. Two of them are entirely black and white; the third has pale colours in the two vases of flowers which sit on each side of a central black and white image of the Crucifixion. In place of Barzelli’s striking floral borders, Gasparo used the traditional lace-work and candelabra decorations for the top and side edges of his altar fronts. The chiaroscuro work is finely executed, giving a satisfying solidity to the images.

Scagliola Paliotto with black and white central image of the crucifixion and two flanking flower vases with faded colouring by Gasparo Griffoni. (Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo c. 1670s).

Black and white scagliola image of St. Anthony of Padua and the Christ child, by Gasparo Griffoni. (Altar detail in the church of Santa Maria della Neve, Motta di Cavezzo c. 1670s)

Paliotto by Gasparo Griffoni in Carpi Cathedral with pictorial scagliola images of Christ and two angels.

A paliotto in Carpi Cathedral by Gasparo Griffoni (doc.1670) has a main section which is split into three panels by two thin pilasters. Each panel is inlaid with a baroque cartouche which frames an image, an Ecce Homo in the centre, and single angels at the two sides. The images, which are rendered in colour, are an early attempt by a Carpigian to produce paintings in scagliola; the results are somewhat crude, but the work is worthy of mention for its innovation.

Marco Mazelli (Carpi 1640-Ferrara last doc. 1713)

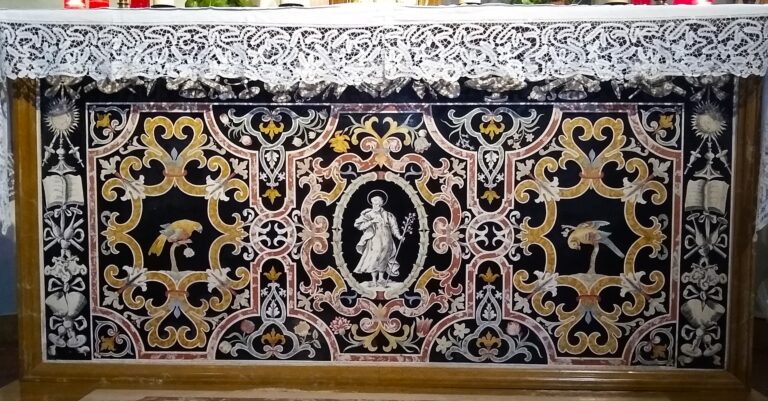

Although from the second generation of Carpigian scagliolists, Marco Mazelli’s work belongs stylistically to both the second and third. This is explained by his long working life; he was seventy-three when he made his last documented altar front. Mazelli used the subtle colours favoured by the Carpigian scagliolists of his generation, set off against a plain black background, and bordered on the top edge and sides with strips of black and white lacework. The design of his early altar pieces has a tripartite organisation, but the stylised candelabra are replaced by imitation marble bandwork surrounding the three main panels. These contain a variety of images: religious figures and events executed in black and white; multi-coloured images of parrots on branches and bunches of flowers; panels of imitation antique marble, including Giallo Antico, Verde Antico and Porphyry.

Scagliola Paliotto with central image depicting St. Peter flanked by parrots. (Abbey of San Pietro, Modena, by Marco Mazelli. 1680’s/90’s).

Mazelli also used the same stencils on different altar pieces, changing the images to give variation. His output was prolific, and there are works from this period of his life in several of the Emilian churches.* In Modena there are examples in the abbey church of San Pietro, the Chiesa di San Vincenzo, the Chiesa del Voto and the Chiesa della Pomposa.

Scagliola paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Chiesa of San Vincenzo (c. 1680’s). Note the identical design of the strapwork in these two works, showing the use of the same stencil and the same colours.

Detail of a parrot surrounded by similar foliage and strapwork, from a paliotto by Marco Mazelli in the Chiesa del Voto, Modena.

At the end of the century he developed a completely new approach. The earliest known example is an altar front he made for the private chapel in the castle of Spezzano di Fiorano (nr. Modena) signed and dated 1699. A similar work taken from the same stencil, originally in the parish church of Sant’Agostino in Modena, can be seen in the city museum (where it was moved in the nineteenth century). In these altar pieces the tripartite scheme has completely disappeared, and the entire picture field is now covered with thick, sinuous foliage containing birds, flowers, fruit, cornucopia and grotesques. Hatching lines are reduced to a minimum, and colour itself is used to create shading and detail.

Scagliola paliotto by Marco Mazelli, created from an identical stencil used for an altar in the private chapel of the Castello di Fiorano near Modena and dated 1699. It was moved to the Civic Museum of Modena in the 19th century.

Pietre Dure elements are still evident in these early baroque designs, but the intention is much closer to painting, and the degree of pictorial realism has gone beyond that achievable with inlaid stone. On the other hand, unlike real paintings these altar slabs could be polished to take on a marble-like appearance, giving them value not only as precious works of art, but also of illusion.

At the turn of the century Mazelli moved to the Duchy of Parma, possibly to avoid competition from Pozzuoli and Massa, younger scagliolists with whom he had worked under Gasparo Griffoni, and who were now active in their own right in the Duchy of Modena (see next Chapter). While there, he supplied a magnificent set of four pairs of altar fronts to the Sanctuary of the Madonna of the Rosary at Fontanellato. They are all in his later style, signed and dated 1701; as in earlier work, identical stencils were used for the decorative elements of each pair, with different images placed within the various cartouches. This was a significant commission, perhaps the largest yet for a single church, and implies that Mazelli had access to several skilled assistants.

One of eight altar fronts by Marco Mazelli in the Sanctuary Church of the Madonna of the Rosary, Fontanellato, Parma (signed and dated 1701).

Shortly after the completion of this work, he moved east to the Papal States, settling in Ferrara. He left works in Ferrara and Ravenna, and his last known altar piece, signed and dated 1713, is in the church of San Paolo in Ferrara.**

* Motta di Cavezzo, Camposanto, Sassuolo, Marzaglia et al. See Manni pp.82-10

** Traditionally Mazelli is credited with introducing the technique to Montefeltro and Le Marche. This is overstated, on the grounds that there is scagliola work in the region which predates his arrival; but nevertheless, the presence of such a skilfull and long-lived scagliolist must have had a significant influence on the spread and popularity of the material.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997