The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

Two names dominate the final period of scagliola manufacture in and around Carpi. Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa, between them active from the last years of the 1680s until the early 1740s, both trained under Gasparo Griffoni. At the beginning of their careers they formed a partnership, producing several signed and dated altar fronts. At the end of the century they went their separate ways, each developing a distinctive personal style.

The partnership of Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa (Carpi 1689-1698).

Their work together can be seen as an extension of Mazelli’s, becoming ever bolder and more baroque in form. Their altar fronts are characterised by a large central cartouche surrounded by dense swirling foliage. Later works include architectural features used to establish strong perspective. As with Mazelli, subtle phasing of the colours – as opposed to black and white cross-hatching – give the illusion of three-dimensionality. The colours themselves are stronger, generating a more dramatic effect against the black backgrounds.

Scagliola altar piece by Pozzuoli and Massa in the parish church of Soliera, nr. Modena. The work is signed and dated 1689. The image depicts Our Lady of the Sorrows, with the three empty crosses in the background.

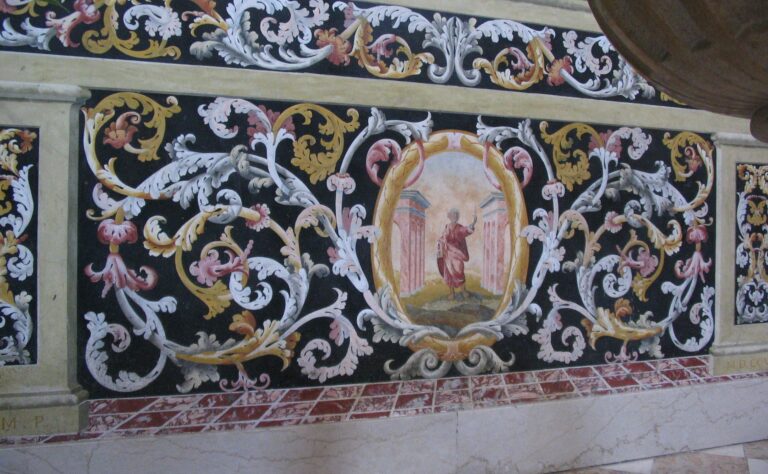

The central cartouches invariably contain scagliola paintings depicting religious events; they are usually set in rural landscapes, with trees, hills and sometimes buildings receding into the distance. Attention is given to composition and perspective, and there is often a separation between an ‘earthly’ dimension and a ‘heavenly’ one.

Close-up of central image.

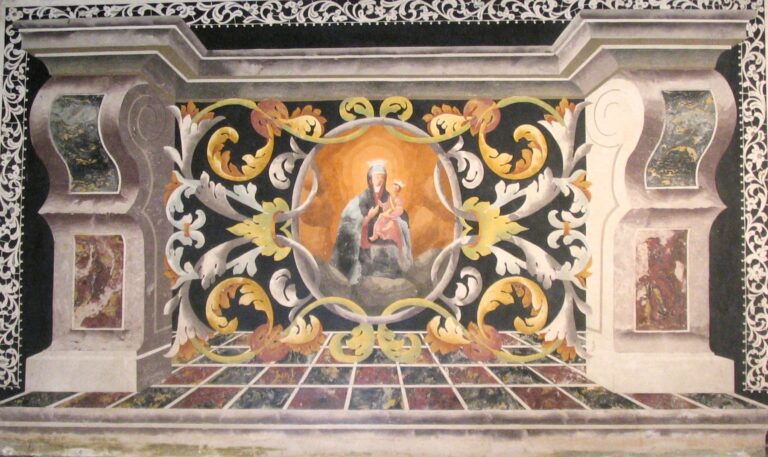

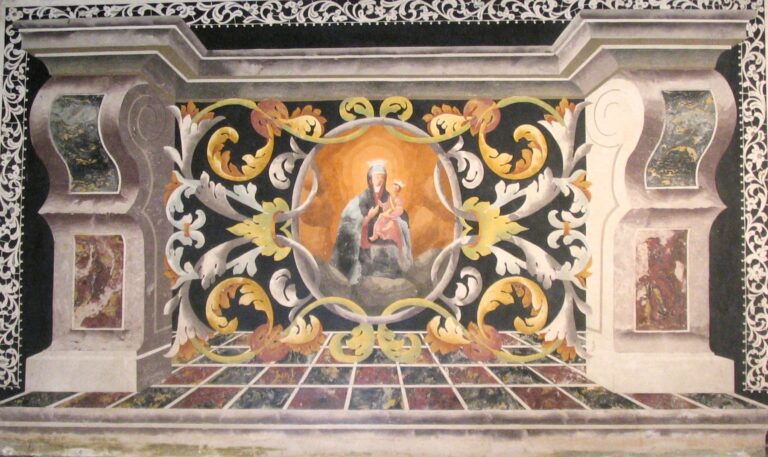

Towards the end of their partnership, as in the example given below, Pozzuoli and Massa increased the sense of depth in their work by placing the main design within an illusory open altar. Two massive consoles, standing on a floor made of square marble tiles, support the heavily moulded edge and underside of a stone altar slab. The consoles are foreshortened and the jointed floor tiles are tapered, creating the appearance of receding space under the altar table. The cartouche and brightly coloured foliage float mysteriously in this space, highlighted against a black background which seems to vanish into infinity. The concept is in the tradition of the theatrum sacrum, very popular in church interiors of the Baroque period, and both makers returned to the format in individual altar pieces they made after their partnership ended.

An altar front made by Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa in the last decade of the 17th century. The illusion of perspective established by the large console blocks and tiled pavement give a feeling of worldly solidity, while the central design with its gold and silver foliage seems to float mysteriously in space. The work was originally housed in a monastery in Carpi and moved to the Civic Museum at the beginning of the 20th century.

There are examples of Pozzuoli and Massa’s work in the parish churches of Quatrirolo and Soliera, also the churches of San Bernardino and Sant’Ignazio in Carpi. In the case of Sant’Ignazio, the main altar front is flanked by two side panels with richly coloured vases of flowers.*

* See Graziano Manni: I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche Page 156.

Giovanni Pozzuoli (Carpi 1646-1734)

After the dissolution of his partnership with Massa, Pozzuoli, now married, moved to San Martino a Rio, between Correggio and Reggio Emilia, where he lived for the rest of his life. There are three altar pieces by him in the nearby church of St. Genesius, Fabbrico.

Two of these, similar in style to his work with Massa, were clearly made as a pair. Both feature a picture space with a black background formed between the two upright piers and lintel of an altar, standing on a receding tiled floor. The illusory piers and lintels have recessed panels in black, inlaid with richly coloured foliage. (The gradine steps above the marble altar tables are similarly inlaid). Central oval frames contain scagliola paintings of Saint Bartholomew with his knife and Saint Genesius in the streets of Rome; in both cases the saints stand between foreshortened arcades, which add to the illusion of depth. In the Saint Bartholomew altar front, the remaining area is filled with dense floating foliage; in the Saint Genesius version, the central image is flanked with two flower vases on stone plinths, which sit forward from the central cartouche, also on a plinth. Both altar fronts have borders of lace in black and white inlay along their top and side edges. The Saint Bartholomew paliotto is signed and dated 1707.*

* According to the 18th century historian Cabassi, the payment records of the parish archive (now lost) stated that Pozzuoli received Lir.200 for this work, and an additional 50 scudi for the scagliola gradine steps. See Manni quoting Cabassi pp 164-6

Altar front by Giovanni Pozzuoli dedicated to St. Bartholomew, signed and dated 1707 (Parish Church of St. Genesius, Fabbrico).

Altar front by Giovanni Pozzuoli dedicated to St. Genesius, who is seen in the central cartouche, flanked by reflecting flower vases. (Parish Church of St. Genesius, Fabbrico c. 1707-1710).

St. Genesius in the streets of Rome. The subtle shading of the sky from light to dark became a striking feature of Massa’s work (see below).

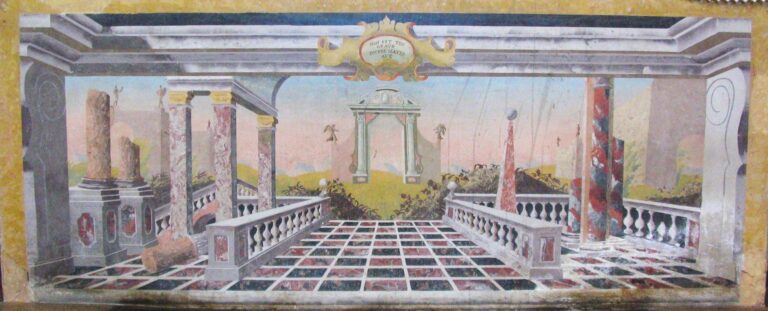

The third paliotto, documented in 1710-11, is a depiction of the Last Supper. It is an ambitious piece that marks a complete break from Pozzuoli’s previous work, and is derived from the new style that Massa had been developing since the turn of the century (see below). There is no longer a black background with decorative foliage; now the entire area is taken up with a picture, the interior view of a classical palace. In the foreground there are Corinthian columns and pilasters with recessed marble panels; archways lead to vaulted arcades where figures are engaged in various activities, presumably religious, and there are views through to the outer world; linking everything together is the floor, a chequerboard design of red and yellow marble tiles which recedes into the far end of the arcades, establishing the different levels of the theatrum sacrum. In the centre of this imaginary interior is a pilastered room on a raised platform, where the Last Supper is taking place. Judas sits in the right-hand foreground, purse in hand, while the other disciples crowd around the seated Christ.*

*Pozzuoli received payments in 1710 (Lir 80) and 1711 (Lir 274) for this work.

Giovanni Pozzuoli’s paliotto depicting the Last Supper. (The Church of St. Genesius, Fabricco, doc. 1710-11)

Details: The Last Supper (centre) and two other religious depictions: possibly Mary taking the young Christ to the Temple (LHS) and the Feeding of the Five Thousand (RHS). Click on images to enlarge.

Many of the architectural elements in this altar piece recall Wilhelm Fistulator’s ‘Life of Mary’ cycle (see Chapter 12), but the work has none of the precision of the Reiche Kapelle pictures; the veining and figuring of the imitation marble is unrealistic, and there are problems of scale and overcrowding in the central scene that make it difficult to read. Nevertheless, there are qualities here that are not present in the earlier German work, particularly in the painterly portrayal of the figures, which shows considerable movement and emotion.

In the 1720s Pozzuoli made a similar altar piece for the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, composed of architectural elements and a depiction of the Adoration of the Shepherds. Two free-standing classical pavilions are seen in the foreground, framing the religious scene which takes place outdoors in the middle distance.*

*This palliotto was attributed by the historian Cabassi to Giovanni Massa, formerly Pozzuli’s partner and now his competitor, on the grounds of stylistic similarities which will appear evident in the next section of this chapter. Manni however finds reasons for attributing it to Pozzuoli, not least because of the closeness of its colouring and design elements to the Fabricco Last Supper. See Manni pp.166-8.

Altar piece by Giovanni Pozzuoli depicting the Adoration of the Shepherds at the Nativity (1720s, Church of San Niccolò, Carpi).

Pozzuoli continued to make scagliola altar fronts until the end of the 1720s. He alternated between his earlier decorative style and the later pictorial approach, sometimes combining the two by enlarging the central image at the expense of the foliage; in a late work (c. 1730) in the parish church of Canolo di Correggio, the central framed image of Santa Lucia occupies a full third of the picture space.

In the same church, one of Pozzuoli’s final works, somewhat damaged, is an altar front which depicts the unhorsing of St Paul. It has none of the decorative apparatus typical of baroque scagliola work: the swirling foliage, birds and insects, imaginary architecture and trompe l’oeil perspectives are completely absent. Apart from a small celestial image at the top, this is a picture, pure and simple, of figures in a landscape. Graziano Manni praises the skill of the work and the liveliness which Pozzuoli brings to the scene; but he also sees the endeavour as evidence that inlaid scagliola, by trying to imitate a painting pure and simple, was nearing the end of its time as an autonomous contributor to the great decorative arts associated with the Counter Reformation.*

*For photos of the Canolo di Correggio altars see Manni pp. 172-3. Regarding his comments on the St Paul altar front, Dr. Erwin Neumann said something similar, stating that inlaid scagliola lost its validity as a decorative art when it made the ‘admittedly logical but fundamentally doomed’ attempt to cross over into painting.

Giovanni Massa (Carpi 1660-1741)

Giovanni Massa was fourteen years younger than Pozzuoli, and the junior member of the partnership. Like his teacher Gasparo Griffoni, he became a priest. Many commentators have considered him the greatest of the Carpi scagliolists, and he was certainly one of the most prolific. According to the 18th century local historian Eustachio Cabassi, who had access to his archive, he ran an organised business and kept accounts and details of all his commissions. He also kept a notebook – unfortunately lost – in which he recorded his ‘various secret experiments’.

He was active throughout the first three decades of the eighteenth century, supplying scagliola altar surrounds and memorial stones to churches in the area to the west of Carpi: Correggio, Guastalla, Novellara, Parma, Cremona and even Turin. There are works of his in the churches of Carpi and Modena. He also made altar surrounds, tabernacles, communion rails and balustrades; and he undertook secular commissions, most of which have been dispersed and lost.*

*An exception is a pair of tabletops signed and dated 1705. Originally commissioned by the Duke of Guastalla, their style is similar to the work produced by the Pozzuoli/Massa partnership at the end of the 1690s. (Although Manni stated in his book that they were held in the Museum of Carpi, they were not on public display in 2023. For photographs see Manni ibid. p. 177).

In 1704 Massa signed and dated an altar front with an image of the Madonna of the Girdle for the collegiate church of San Quirino in Correggio. For this he developed an original format using a pictorial design that filled the entire area of the work. (The style was copied a few years later by Pozzuoli in his ‘Last Supper’ paliotto – see above).

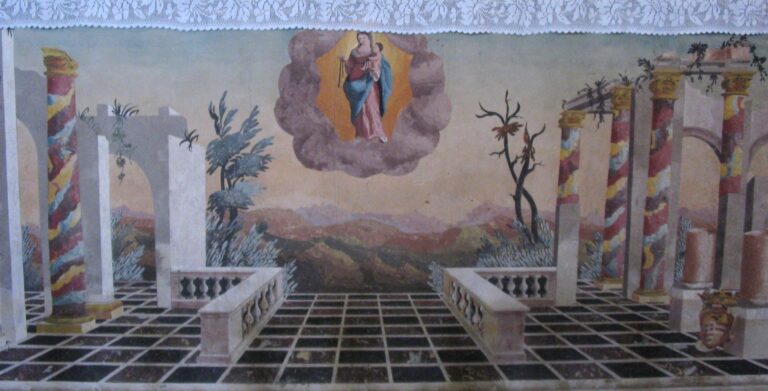

Scagliola paliotto by Giovanni Massa, signed and dated 1704, showing a celestial image of the Madonna of the Girdle (Collegiate Church of San Quirino, Correggio).

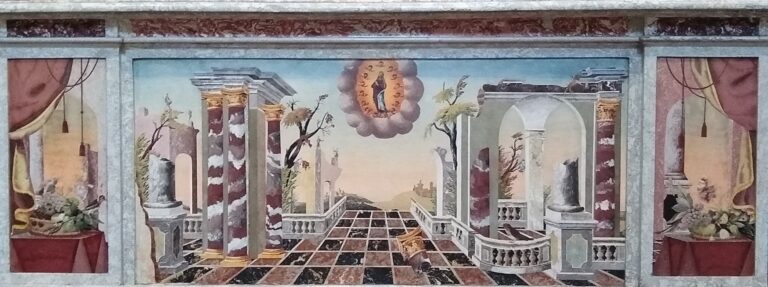

In the foreground a pavement of receding marble tiles supports classical ruins comprised of marble columns and archways. A balustrade leads to the back edge of the pavement, from which the ground drops away unseen. In the background, ranges of hills fade into the distance. A spectacular arcadian sky fills nearly half of the picture, changing imperceptibly from blue at the top to pale yellow where it meets the hills. Framed in clouds is a celestial image of the Madonna.

This altar front contains all the distinctive characteristics of Massa’s later work, which he continued to use throughout his long career. He varied the positioning of the religious figures or events to suit his purpose, sometimes incorporating them into the foreground, sometimes omitting them altogether, leaving a surreal sense of emptiness.

St. Peter kneels to receive the Keys to the Church from Christ in a fantasy setting that is typical of Massa. Once again a tiled and balustraded terrace with ruined classical architecture leads the eye (on this occasion past the figures) towards a pastoral background. An angel surveys the scene from a cloud floating overhead. (Carpi Cathedral, undated).

Scagliola altar piece by Massa without religious imagery (Chiesa della Santa Maria della Porta, Guastalla).

The most striking quality in these works is the depiction of space and distance, which Massa achieved partly through design and the tightly controlled use of perspective, partly through the skill of his technique. In each of his works the ground drops away out of sight beyond the far edge of the pavement, (a useful device which avoids the problematic portrayal of middle ground). At the same time the landscape, initially well-defined with trees and buildings, seems to dissolve as it approaches the distant horizon. The skies, reminiscent of renaissance religious painting, involve a technique which is difficult to achieve in scagliola, that of phasing one colour into another without a visible break. This is done by creating a sequence of colours that runs in a smooth progression from one end of the chosen spectrum to the other; if there are insufficient gradations, faint ‘stripes’ appear between the individual strips of inlay.

It is easy to forget that these seamless scagliola ‘paintings’ with their subtle gradations of colour and shading were all produced by inlaying individual coloured and marbled mixes of plaster.

An austere and moving depiction of La Pietà, with the empty crosses on the hill of Golgotha outlined against a darkening sky. One of a series of panels created by Giovanni Massa for the Chiesa dei Serviti, Guastalla, probably in the 1730s when he was at the height of his powers.

Scagliola paliotto by Giovanni Massa depicting the Assumption of the Virgin, considered by both Neumann and Mani to be one of his most accomplished pieces. The central picture is flanked by two scagliola Still Life panels (Carpi Cathedral c. 1730-35)

***

To modern eyes the colours and figuring of Massa’s columns may seem garish and improbable, particularly when considered against the overall quality and precision of his work.

Brightly coloured columns from one of Massa’s panels in the Chiesa dei Serviti, Guastala.

Giovanni Massa’s output was considerable, the most of any of the Carpi scagliolists, and it may be that quality suffered at the hands of the large staff he needed to help him. On the other hand these very brightly coloured columns appear in the majority of his altar pieces, and must have been acceptable to both Massa and his clients. The vivid colours – reds, blues and golds – would undoubtedly have held symbolic meaning for the faithful (see next chapter on Christian symbolism).

They may also have served a more decorative function. Neumann thought that Massa’s altarpieces – unlike the ‘stand-alone’ works of the earlier scagliolists – were designed to play a complimentary role in the overall decoration of the church, as functional elements of the Gesamtkunstwerk.* They performed the same function below, at ground level, as the brightly painted trompe l’oeil ceilings above; the expansion of space and the opening up of earthly realms to the spiritual world beyond.

* The term Gesamtkunstwerk – literally ‘a synthesis of the arts’ – is used in the context of church interiors to describe a situation where all the different decorative arts, and the architecture itself, are deployed in the creation of a single work of art, in this case the church itself. It is frequently used when discussing the Baroque and Rococo churches of Southern Germany, where the use of architectural scagliola is extremely prevalent. (See Chapter..)

***

Pozzuoli and Massa were the last of the great Carpi scagliolists, and the work of those who followed became increasingly repetitive and provincial.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola Carpigiana e l’Illusione Barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 p. 112.

Two names dominate the final period of scagliola manufacture in and around Carpi. Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa, between them active from the last years of the 1680s until the early 1740s, both trained under Gasparo Griffoni. At the beginning of their careers they formed a partnership, producing several signed and dated altar fronts. At the end of the century they went their separate ways, each developing a distinctive personal style.

The partnership of Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa (Carpi 1689-1698)

Their work together can be seen as an extension of Mazelli’s, becoming ever bolder and more baroque in form. Their altar fronts are characterised by a large central cartouche surrounded by dense swirling foliage. Later works include architectural features used to establish strong perspective. As with Mazelli, subtle phasing of the colours – as opposed to black and white cross-hatching – give the illusion of three-dimensionality. The colours themselves are stronger, generating a more dramatic effect against the black backgrounds.

Scagliola altar piece by Pozzuoli and Massa in the parish church of Soliera, nr. Modena. The work is signed and dated 1689. The image depicts Our Lady of the Sorrows, with the three empty crosses in the background.

The central cartouches invariably contain scagliola paintings depicting religious events; these are usually set in rural landscapes, with trees, hills and sometimes buildings receding into the distance. Attention is given to composition and perspective, and there is often a separation between an ‘earthly’ dimension and a ‘heavenly’ one.

Close-up of central image.

Towards the end of their partnership, as in the example given below, Pozzuoli and Massa increased the sense of depth in their work by placing the main design within an illusory open altar. Two massive consoles, standing on a floor made of square marble tiles, supports the heavily moulded edge and underside of a stone altar slab. The consoles are foreshortened and the jointed floor tiles are tapered, creating the appearance of receding space under the altar table. The cartouche and brightly coloured foliage float mysteriously in this space, highlighted against a black background which seems to vanish into infinity. The concept is in the tradition of the theatrum sacrum, very popular in church interiors of the Baroque period, and both makers returned to the format in individual altar pieces they made after their partnership ended.

An altar front made by Giovanni Pozzuoli and Giovanni Massa in the last decade of the 17th century. The illusion of perspective established by the large console blocks and tiled pavement give a feeling of worldly solidity, while the central design with its gold and silver foliage seems to float mysteriously in space. The work was originally housed in a monastery in Carpi and moved to the Civic Museum at the beginning of the 20th century.

There are examples of Pozzuoli and Massa’s work in the parish churches of Quatrirolo and Soliera, also the churches of San Bernardino and Sant’Ignazio in Carpi. In the case of Sant’Ignazio, the main altar front is flanked by two side panels with richly coloured vases of flowers.*

* See Graziano Manni: I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche Page 156.

Giovanni Pozzuoli (Carpi 1646-1734)

After the dissolution of his partnership with Massa, Pozzuoli, now married, moved to San Martino a Rio, between Correggio and Reggio Emilia, where he lived for the rest of his life. There are three altar pieces by him in the nearby church of Fabbrico.

Two of these, similar in style to his work with Massa, were clearly made as a pair. Both feature a picture space with a black background formed between the two upright piers and lintel of an altar, standing on a receding tiled floor. The illusory piers and lintels have recessed panels in black, inlaid with richly coloured foliage. (The gradine steps above the marble altar tables are similarly inlaid). Central oval frames contain scagliola paintings of Saint Bartholomew with his knife and Saint Genesius in the streets of Rome; in both cases the saints stand between foreshortened arcades, which add to the illusion of depth. In the Saint Bartholomew altar front, the remaining area is filled with dense floating foliage; in the Saint Genesius version, the central image is flanked with two flower vases on stone plinths, which sit forward from the central cartouche, also on a plinth. Both altar fronts have borders of lace in black and white inlay along their top and side edges. The Saint Bartholomew paliotto is signed and dated 1707.*

* According to the 18th century historian Cabassi, the payment records of the parish archive (now lost) stated that Pozzuoli received Lir.200 for this work, and an additional 50 scudi for the scagliola gradine steps. See Manni quoting Cabassi pp 164-6

Altar front by Giovanni Pozzuoli dedicated to St. Bartholomew, signed and dated 1707 (Parish Church of St. Genesius, Fabbrico).

Altar front by Giovanni Pozzuoli dedicated to St. Genesius, who is seen in the central cartouche, flanked by reflecting flower vases. (Parish Church of St. Genesius, Fabbrico c. 1707-1710).

St. Genesius in the streets of Rome. The subtle shading of the sky from light to dark became a striking feature of Massa’s work (see below).

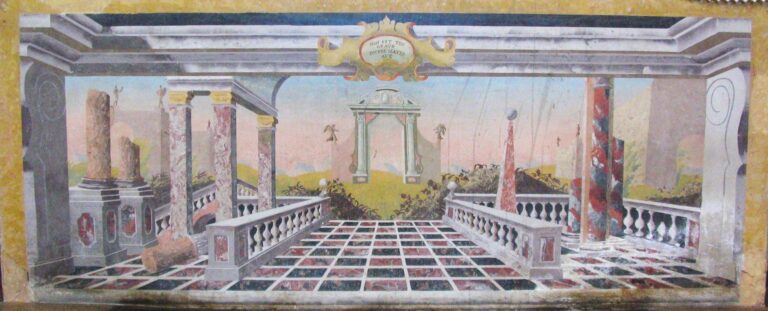

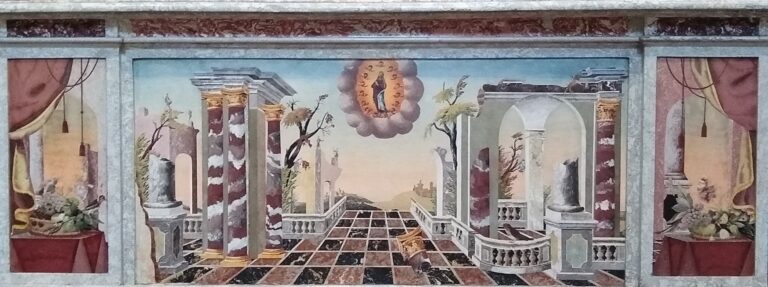

The third paliotto, documented in 1710-11, is a depiction of the Last Supper. It is an ambitious piece that marks a complete break from Pozzuoli’s previous work, and is derived from the new style that Massa had been developing since the turn of the century (see below). There is no longer a black background with decorative foliage; now the entire area is taken up with a picture, the interior view of a classical palace. In the foreground there are Corinthian columns and pilasters with recessed marble panels; archways lead to vaulted arcades where figures are engaged in various activities, presumably religious, and there are views through to the outer world; linking everything together is the floor, a chequerboard design of red and yellow marble tiles which recedes into the far end of the arcades, establishing the different levels of the theatrum sacrum. In the centre of this imaginary interior is a pilastered room on a raised platform, where the Last Supper is taking place. Judas sits in the right-hand foreground, purse in hand, while the other disciples crowd around the seated Christ.*

*Pozzuoli received payments in 1710 (Lir 80) and 1711 (Lir 274) for this work.

Giovanni Pozzuoli’s paliotto depicting the Last Supper. (The Church of St. Genesius, Fabricco, doc. 1710-11)

Details: The Last Supper (centre) and two other religious depictions: possibly Mary taking the young Christ to the Temple (LHS) and the Feeding of the Five Thousand (RHS). Click on images to enlarge.

Many of the architectural elements in this altar piece recall Wilhelm Fistulator’s ‘Life of Mary’ cycle (see Chapter 12), but the work has none of the precision of the Reiche Kapelle pictures; the veining and figuring of the imitation marble is unrealistic, and there are problems of scale and overcrowding in the central scene that make it difficult to read. Nevertheless, there are qualities here that are not present in the earlier German work. Space is strongly defined within the different areas of the building, and there is considerable movement and emotion in the painterly portrayal of the figures.

In the 1720s Pozzuoli made a similar altar piece for the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, composed of architectural elements and a depiction of the Adoration of the Shepherds. Two free-standing classical pavilions are seen in the foreground, framing the religious scene which takes place outdoors in the middle distance.*

*This palliotto was attributed by Cabassi to Giovanni Massa, formerly Pozzuli’s partner and now his competitor, on the grounds of stylistic similarities which will appear evident in the next section of this chapter. Manni however finds reasons for attributing it to Pozzuoli, not least because of the closeness of its colouring and design elements to the Fabricco Last Supper. See Manni pp.166-8.

Altar piece by Giovanni Pozzuoli depicting the Adoration of the Shepherds at the Nativity (1720s, Church of San Niccolò, Carpi).

Pozzuoli continued to make scagliola altar fronts until the end of the 1720s. He alternated between his earlier decorative style and the later pictorial approach, sometimes combining the two by enlarging the central image at the expense of the foliage; in a late work (c. 1730) in the parish church of Canolo di Correggio, the central framed image of Santa Lucia occupies a full third of the picture space.

In the same church, one of Pozzuoli’s final works, somewhat damaged, is an altar front which depicts the unhorsing of St Paul. It has none of the decorative apparatus typical of baroque scagliola work: the swirling foliage, birds and insects, imaginary architecture and trompe l’oeil perspectives are completely absent. Apart from a small celestial image at the top, this is a picture, pure and simple, of figures in a landscape. Graziano Manni praises the skill of the work and the liveliness which Pozzuoli brings to the scene; but he also sees the endeavour as evidence that inlaid scagliola, by trying to imitate a painting pure and simple, was nearing the end of its time as an autonomous contributor to the great decorative arts associated with the Counter Reformation.*

*For photos of the Canolo di Correggio altars see Manni pp. 172-3. Regarding his comments on the St. Paul altar front, Dr. Erwin Neumann said something similar, stating that inlaid scagliola lost its validity as a decorative art when it made the ‘admittedly logical but fundamentally doomed’ attempt to cross over into painting.

Giovanni Massa (Carpi 1660-1741)

Giovanni Massa was fourteen years younger than Pozzuoli, and the junior member of the partnership. Like his teacher Gasparo Griffoni, he became a priest. Many commentators have considered him the greatest of the Carpi scagliolists, and he was certainly one of the most prolific. According to the 18th century local historian Eustachio Cabassi, who had access to his archive, he ran an organised business and kept accounts and details of all his commissions. He also kept a notebook – unfortunately lost – in which he recorded his ‘various secret experiments’.

He was active throughout the first three decades of the eighteenth century, supplying scagliola altar surrounds and memorial stones to churches in the area to the west of Carpi: Correggio, Guastalla, Novellara, Parma, Cremona and even Turin. There are works of his in the cathedrals of Carpi and Modena. He also made architectural scagliola: altar surrounds, tabernacles, communion rails and balustrades; and he undertook secular commissions, most of which have been dispersed and lost.*

*An exception is a pair of tabletops signed and dated 1705. Originally commissioned by the Duke of Guastalla, their style is similar to the work produced by the Pozzuoli/Massa partnership at the end of the 1690s. Although Manni stated in his book that they were held in the Museum of Carpi, they were not on public display in 2023. For photographs see Manni ibid. p. 177

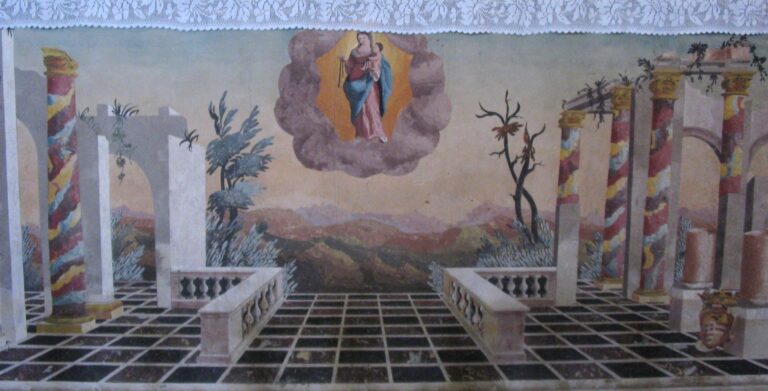

In 1704 Massa signed and dated an altar front with an image of the Madonna of the Girdle for the collegiate church of San Quirino in Correggio. For this he developed an original format, a pictorial design that filled the entire area of the work. In the foreground a pavement of receding marble tiles supports classical ruins made up of marble columns and archways. A balustrade leads to the back edge of the pavement, from which the ground drops away unseen. In the background, ranges of hills fade into the distance. A spectacular arcadian sky fills nearly half of the picture, changing imperceptibly from blue at the top to pale yellow where it meets the hills; framed in clouds is a celestial image of the Madonna.

Scagliola paliotto by Giovanni Massa, signed and dated 1704, showing a celestial image of the Madonna of the Girdle (Collegiate Church of San Quirino, Correggio).

In the foreground a pavement of receding marble tiles supports classical ruins comprised of marble columns and archways. A balustrade leads to the back edge of the pavement, from which the ground drops away unseen. In the background, ranges of hills fade into the distance. A spectacular arcadian sky fills nearly half of the picture, changing imperceptibly from blue at the top to pale yellow where it meets the hills. Framed in clouds is a celestial image of the Madonna.

This altar front contains all the distinctive characteristics of Massa’s later work, which he continued to use throughout his long career. He varied the positioning of the religious figures or events to suit his purpose, sometimes incorporating them into the foreground, sometimes omitting them altogether, leaving a surreal sense of emptiness.

St. Peter kneels to receive the Keys to the Church from Christ in a fantasy setting that is typical of Massa. Once again a tiled and balustraded terrace with ruined classical architecture leads the eye (on this occasion past the figures) towards a pastoral background. An angel surveys the scene from a cloud floating overhead. (Carpi Cathedral, undated).

Scagliola altar piece by Massa without religious imagery (Chiesa della Santa Maria della Porta, Guastalla).

The most striking quality in these works is the depiction of space and distance, which Massa achieved partly through design and the tightly controlled use of perspective, partly through the skill of his technique. In each of his works the ground drops away out of sight beyond the far edge of the pavement, (a useful device which avoids the problematic portrayal of middle ground). At the same time the landscape, initially well-defined with trees and buildings, seems to dissolve as it approaches the distant horizon. The skies, reminiscent of renaissance religious painting, involve a technique which is difficult to achieve in scagliola, that of phasing one colour into another without a visible break. This is done by creating a sequence of colours that runs in a smooth progression from one end of the chosen spectrum to the other; if there are insufficient gradations, faint ‘stripes’ appear between the individual strips of inlay.

It is easy to forget that these seamless scagliola ‘paintings’ with their subtle gradations of colour and shading were all produced by inlaying individual coloured and marbled mixes of plaster.

An austere and moving depiction of La Pietà, with the empty crosses on the hill of Golgotha outlined against a darkening sky. One of a series of panels created by Giovanni Massa for the Chiesa dei Serviti, Guastalla, probably in the 1730s when he was at the height of his powers.

Scagliola paliotto by Giovanni Massa depicting the Assumption of the Virgin, considered by both Neumann and Mani to be one of his most accomplished pieces. The central picture is flanked by two scagliola Still Life panels (Carpi Cathedral c. 1730-35)

***

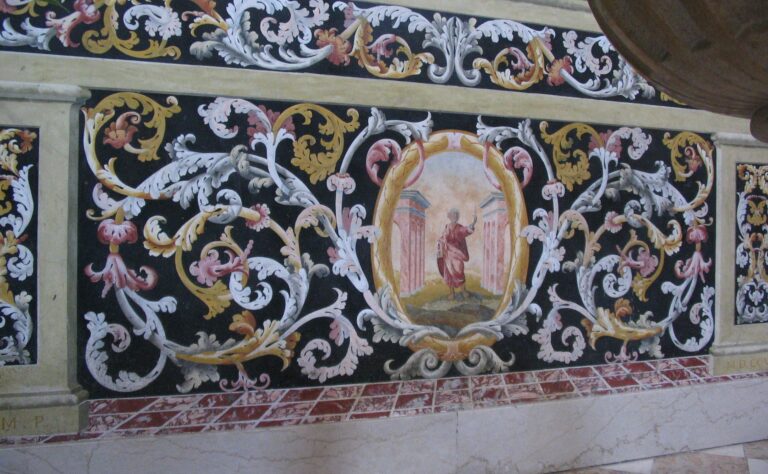

To modern eyes the colours and figuring of Massa’s columns may seem garish and improbable, particularly when considered against the overall quality and precision of his work.

Brightly coloured columns from one of Massa’s panels in the Chiesa dei Serviti, Guastala.

Giovanni Massa’s output was considerable, the most of any of the Carpi scagliolists, and it may be that quality suffered at the hands of the large staff he needed to help him. On the other hand these very brightly coloured columns appear in the majority of his altar pieces, and must have been acceptable to both Massa and his clients. The vivid colours – reds, blues and golds – would undoubtedly have held symbolic meaning for the faithful (see next chapter on Christian symbolism).

They may also have served a more decorative function. Neumann thought that Massa’s altarpieces – unlike the ‘stand-alone’ works of the earlier scagliolists – were designed to play a complimentary role in the overall decoration of the church, as functional elements in a Gesamtkunstwerk.* They performed the same function below, at ground level, as the brightly painted trompe l’oeil ceilings above – the expansion of space and the opening up of earthly realms to the spiritual world beyond.

* The term Gesamtkunstwerk – literally a ‘synthesis of the arts’ – is used in the context of church interiors to describe a situation where all the different decorative arts, and the architecture itself, are deployed in the creation of a single work of art, in this case the church itself. It is frequently used when discussing the Baroque and Rococo churches of Southern Germany, where the use of architectural scagliola is extremely prevalent. (See Chapter..)

***

Pozzuoli and Massa were the last of the great Carpi scagliolists, and the work of those who followed became increasingly repetitive and provincial.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola Carpigiana e l’Illusione Barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997.

Erwin Neumann: Materialen zur Geschichte der Scagliola in ‚Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien’, 55, 1959 p. 112.