The History of Scagliola by Richard Feroze

Menu

Guido Fassi/Guido del Conte (Carpi 1584-1640)

Guido Fassi was not the inventor of scagliola (see Chapter 16), but he can take the credit for introducing it to his home town of Carpi. He was the first Italian to demonstrate its value within the context of religious furnishings, and the subsequent success of the Carpi scagliolists undoubtedly owes much to his artistic and commercial vision.

The earliest example of scagliola in Carpi is an inlaid memorial stone in the cathedral dedicated to Cristoforo Priori and dated 1611. It has been accredited to Guido Fassi, although the actual maker may well have come from the Munich team working in Mantua at the turn of the century (see Chapter 16). The extent to which Fassi himself was involved in hands-on manufacture is unknown. As an architect and designer he would have been occupied with the design side of the workshop’s projects, as well as marketing his new material to those who could afford to pay for it.

An inlaid memorial stone in scagliola in Carpi Cathedral, dedicated to Cristoforo Priori and dated 1611.*

Fassi is known to have produced four large architectural altar surrounds in scagliola, in the same austerely mannerist style as Blasius Fistulator’s monumental pieces in the Munich Antiquarium. Two of these survive: the altar of the Assumption (today the altar of Our Lady of the Sorrows – built 1629) in Carpi Cathedral; and the altar of the Immaculate Conception (built 1633) in the nearby church of San Niccolò.

Scagliola panels imitating coloured marbles by Guido Fassi in the chapel of the Assumption, Carpi Cathedral, 1629. (Altar front by Giovanni Gavignani, 1670s).

In both cases the scagliola work consists of ascending pedestal blocks on either side of the altar, supporting Corinthian pilasters and columns; these in turn support elaborate pediments with mouldings and ornamental urns. A variety of different marbles are imitated, somewhat less convincingly than those of the Fistulators. The surround of the Assumption altar contains plain inlays of squares, ovals and circles within white borders, reminiscent of the style, if not the richness, of the Capella dei Principi in Florence I. (See Chapter 3. Florentine Mosaic). These appear to be the only inlays that Fassi attempted; the intricate inlaid altar fronts are later additions from the 1670s by Giovanni Gavignani (see below).

Scagliola altar surround by Guido Fassi in the chapel of the Assumption, church of San Niccolò, Carpi, 1633. (Altar front by Giovanni Gavignani, 1670s).

*Cristoforo Priori’s memorial stone was first brought to public attention by Alfonso Garuti in La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990 pp 65-66.

Annibale Griffoni (Carpi 1618-1679)

Annibale Griffoni (documented by Eustachio Cabassi) was the nephew and pupil of Guido Fassi, and the first Carpigian to have made an altar front using inlaid scagliola. As well as inlaying geometrical shapes in contrasting colours in the style of his uncle, Griffoni developed a technique which imitated copperplate etching. He used it to simulate the decorative lace cloth that covered the top edge and the sides of an altar, and he went on to create intricate designs and sacred pictures which he copied from popular prints of the saints and biblical events. The results were similar to the ivory and ebony inlaid panels that had become popular on both sides of the Alps, particularly in the decoration of ornate chests and display cabinets. This ‘black-and-white’ scagliola, which was quite unknown in Munich, became a distinguishing feature of seventeenth and early eighteenth century Italian inlaid work.

Close-up of inlaid paliotto (see also Chapter 17, first image) by Annibale Griffoni, Church of San Nicolo, Carpi c.1650.

Examples of Annibale Griffoni’s work can be seen in the parish church of Cavezzo, near Modena (signed) and the church of San Niccolò, Carpi. In both cases the top edge shows a ‘lacework’ frieze of scrolling acanthus in which cherubs are seen playing. Beneath the frieze, there are three identically sized panels, each with coloured geometrical inlays and a central religious image. (In the case of the San Niccolò altar front, the two side panels are inlaid with the coat of arms of the Pace family, the original donors of the chapel). The three panels are contained within four vertical strips depicting candelabra with foliage, grotesques and cherubs. The coloured imitation marble recalls Guido Fassi’s work, but the frieze, the candelabra and the religious images are all executed in the new black and white technique.

The tripartite design of Griffoni’s altar fronts was traditional; it had been used since the Middle Ages in embroidered cloth paliotti, and was a reference to the Trinity. It remained the standard form for the Carpi scagliolists until the last quarter of the 1600s, when experiments with freer designs began to appear.

Close-up of frieze detail by Annibale Griffoni, Church of San Nicolo, Carpi c.1650.

The technique was ingenious, and relied on the precision of the craftsman’s drawing and carving abilities. Although it appears as though the white or ‘ivory’ part of the design has been inlaid into a black background, in fact the reverse is true. The design was initially transferred from a full-size template onto a finished surface of white scagliola, using the ‘prick-and-pounce’ method. The areas intended for the black background were cut away, and the lines for the drawing and cross-hatching carved in. The entire surface was then covered with a thin layer of black scagliola. This was allowed to set hard before it was sanded back to reveal the white body of the design, which now appeared to be inlaid or etched into the black background.

Damaged corner of a paliotto. It is clear from its extreme thinness that the black scagliola was added at the end of the process. The layer of white scagliola, in which the design was carved, is visible between the black and the thick grey substrate.

There were several advantages to working this way round. It was easier and cleaner to draw the design and carve it onto a white surface than a black one. It was also possible to seal the white scagliola through a process of sanding and grouting before the design was cut away. This greatly reduced the problem of colour pollution from the black to the white scagliola. And while some fine-tuning was inevitable after the black coat had been applied and sanded back, most of the detail was carved in beforehand, saving time and again reducing the chance of colour pollution.

Black and white scagliola panel of St. Francis receiving the stigmata. The panel is one of three in a paliotto attributed to Annibale Griffoni, although the quality of the work suggests it may be by a later artist. Church of San Nicolo, Carpi.

Giovanni Gavignani (Carpi 1632-1680)

Giovanni Gavignani, who is said to have learnt from both Guido Fassi and Annibale Griffoni, produced altar fronts almost exclusively in black and white. His work reinforced the tripartite design of the paliotto and formalised it through the absence of colour. His pictorial skill, his dexterity as a carver, and the extraordinary amount of decorative detail that went into his designs, more than compensate for this; the subtle calibration of the cross-hatching – no easy thing to achieve in a material that chips so easily – gives considerable depth and expression to his figurative work.

His masterpiece is the altar to St. Anthony of Padua, in the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, signed and dated 1652, when he was just 20 years old. Of note are the magnificent flower vases in the two outer panels, strongly reminiscent of Wilhelm Fistulator’s vases in the Reiche Kapelle in Munich (c. 1630). Where some of Fistulator’s vases have a pair of butterflies hovering at the base of his vases, Gavignani included, alongside various flying insects, a spider dangling from a thread, presumably a symbol that held religious significance. Some commentators have seen the similarities between the designs as proof of collusion between Munich and Carpi, but a more probable explanation is that the two makers were working from similar prints that were circulating throughout Europe in the 17th century.

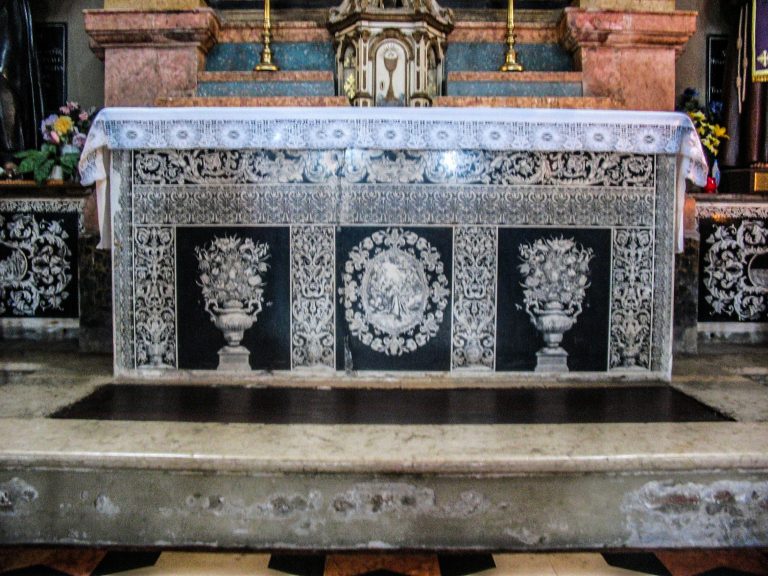

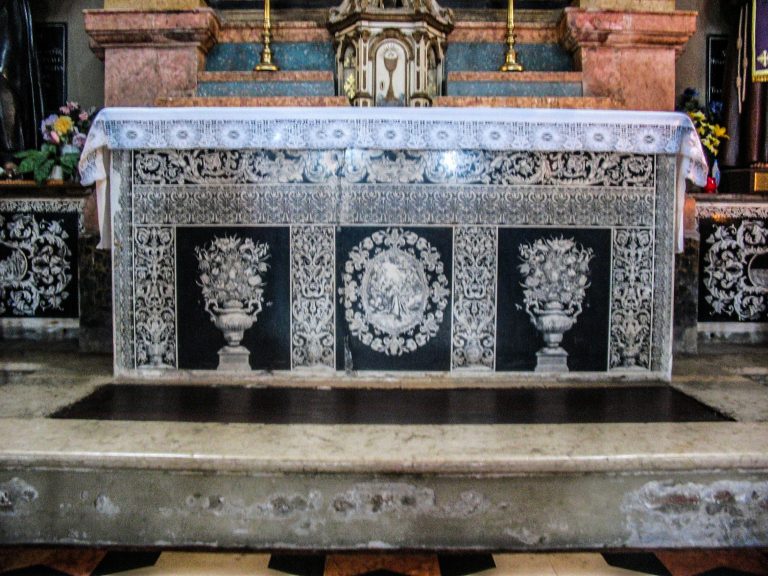

Altar dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua, in the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, by Giovanni Gavignano (signed and dated 1652).

Equally impressive in the St. Anthony altar front are the precision and detailing of the decorative ‘lace work’ around the edge, the frieze of scrolling acanthus across the top, and the four candelabra with antique vases, thick foliage and cornucopia. The central panel contains a picture of St. Anthony in adoration of the Christ child, taken from a print by Simone Cantorini.* The same subject appears in the painting above the altar. Unusually, there are two side altars, also faced with black and white scagliola. Each has a central panel with the depiction of an event from the Saint’s life, set in an inlaid oval frame surrounded with swirling foliage.

*Alfonso Garuti ibid. p 79

Details from the Altar to St. Anthony of Padua.

Gavignani is also credited with the scagliola altar surround, consisting of pedestals, columns and a pediment, similar in style to the work of Guido Fassi. For this he used a restrained colour palette of pale brownish pinks, greys and black.

A striking altar surround by Gavignani, both in terms of its colours and its modelling, is the altar of the Annunciation in the same church of San Niccolò. Black and gold scagliola for the columns and gradine (the ‘step’ above the altar table), provide a dramatic contrast with the brownish pinks used in the other areas. Paired consoles, one reversed on top of the other, form the outer edges of the reredos, an early example of baroque influence. The black and white scagliola altar front is also by Gavignani; the central image depicts the Annunciation, while the two side panels carry the coat of arms of the Barzelli family (one of whose members became a scagliolist – see below).

The Altar of the Annunciation, San Niccolò, Carpi. Paliotto and Surround by Giovanni Gavignano.

Gavignani was a prolific maker, and several of his works, signed and dated, can be seen in the Cathedral and the church of San Niccolò in Carpi. It is clear that he used the same designs on different altar fronts, sometimes interspersing them or varying them slightly, at other times repeating them exactly; fourteen years after making the St Anthony of Padua paliotto for San Niccolò, he made an exact copy for the Church of the Madonna of Lourdes in Reggiolo. He is also reported to have made memorial tablets, tabletops and small religious panels, the latter for domestic use as private objects of contemplation. He had a brother named Pietro Gavignani, who became ‘capo e maestro dell’arte della scagliola’ in 1644, and worked exclusively alongside him; no independent works of Pietro have been identified.

Giovanni Gavignani was the most accomplished of the first generation of Emilian scagliolists, a considerable artist and craftsman, whose mastery of the black and white inlaying technique was never surpassed. He died comparatively young, aged forty-eight.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola Carpigiana e l’Illusione Barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997

Next/Chapter 19: The Carpi Masters – 2nd Generation

Guido Fassi/Guido del Conte (Carpi 1584-1640)

Guido Fassi was not the inventor of scagliola (see Chapter 16), but he can take the credit for introducing it to his home town of Carpi. He was the first Italian to demonstrate its value within the context of religious furnishings, and the subsequent success of the Carpi scagliolists undoubtedly owes much to his artistic and commercial vision.

The earliest example of scagliola in Carpi is an inlaid memorial stone in the cathedral dedicated to Cristoforo Priori and dated 1611. It has been accredited to Guido Fassi, although the actual maker may well have come from the Munich team working in Mantua at the turn of the century (see Chapter 16). The extent to which Fassi himself was involved in hands-on manufacture is unknown. As an architect and designer he would have been occupied with the design side of the workshop’s projects, as well as marketing his new material to those who could afford to pay for it.

An inlaid memorial stone in scagliola in Carpi Cathedral, dedicated to Cristoforo Priori and dated 1611.*

Fassi is known to have produced four large architectural altar surrounds in scagliola, in the same austerely mannerist style as Blasius Fistulator’s monumental pieces in the Munich Antiquarium. Two of these survive: the altar of the Assumption (today the altar of Our Lady of the Sorrows – built 1629) in Carpi Cathedral; and the altar of the Immaculate Conception (built 1633) in the nearby church of San Niccolò.

Scagliola panels imitating coloured marbles by Guido Fassi in the chapel of the Assumption, Carpi Cathedral, 1629. (Altar front by Giovanni Gavignani, 1670s).

In both cases the scagliola work consists of ascending pedestal blocks on either side of the altar, supporting Corinthian pilasters and columns; these in turn support elaborate pediments with mouldings and ornamental urns. A variety of different marbles are imitated, somewhat less convincingly than those of the Fistulators. The surround of the Assumption altar contains plain inlays of squares, ovals and circles within white borders, reminiscent of the style, if not the richness, of the Capella dei Principi in Florence I. (See Chapter 3. Florentine Mosaic). These appear to be the only inlays that Fassi attempted; the intricate inlaid altar fronts are later additions from the 1670s by Giovanni Gavignani (see below).

Scagliola altar surround by Guido Fassi in the chapel of the Assumption, church of San Niccolò, Carpi, 1633. (Altar front by Giovanni Gavignani, 1670s).

*Cristoforo Priori’s memorial stone was first brought to public attention by Alfonso Garuti in La Scagliola carpigiana e l’illusione barocca, Modena 1990 pp 65-66.

Annibale Griffoni (documented by Eustachio Cabassi) was the nephew and pupil of Guido Fassi, and the first Carpigian to have made an altar front using inlaid scagliola. As well as inlaying geometrical shapes in contrasting colours in the style of his uncle, Griffoni developed a technique which imitated copperplate etching. He used it to simulate the decorative lace cloth that covered the top edge and the sides of an altar, and he went on to create intricate designs and sacred pictures which he copied from popular prints of the saints and biblical events. The results were similar to the ivory and ebony inlaid panels that had become popular on both sides of the Alps, particularly in the decoration of ornate chests and display cabinets. This ‘black-and-white’ scagliola, which was quite unknown in Munich, became a distinguishing feature of seventeenth and early eighteenth century Italian inlaid work

Inlaid paliotto (see also Chapter 17, first image) by Annibale Griffoni, Church of San Nicolo, Carpi c.1650.

Examples of Annibale Griffoni’s work can be seen in the parish church of Cavezzo, near Modena (signed) and the church of San Niccolò, Carpi. In both cases the top edge shows a ‘lacework’ frieze of scrolling acanthus in which cherubs are seen playing. Beneath the frieze, there are three identically sized panels, each with coloured geometrical inlays and a central religious image. (In the case of the San Niccolò altar front, the two side panels are inlaid with the coat of arms of the Pace family, the original donors of the chapel). The three panels are contained within four vertical strips depicting candelabra with foliage, grotesques and cherubs. The coloured imitation marble recalls Guido Fassi’s work, but the frieze, the candelabra and the religious images are all executed in the new black and white technique.

The tripartite design of Griffoni’s altar fronts was traditional; it had been used since the Middle Ages in embroidered cloth paliotti, and was a reference to the Trinity. It remained the standard form for the Carpi scagliolists until the last quarter of the 1600s, when experiments with freer designs began to appear.

Close-up of frieze detail by Annibale Griffoni, Church of San Nicolo, Carpi c.1650.

The technique was ingenious, and relied on the precision of the craftsman’s drawing and carving abilities. Although it appears as though the white or ‘ivory’ part of the design has been inlaid into a black background, in fact the reverse is true. The design was initially transferred from a full-size template onto a finished surface of white scagliola, using the ‘prick-and-pounce’ method. The areas intended for the black background were cut away, and the lines for the drawing and cross-hatching carved in. The entire surface was then covered with a thin layer of black scagliola. This was allowed to set hard before it was sanded back to reveal the white body of the design, which now appeared to be inlaid or etched into the black background.

Damaged corner of a paliotto. It is clear from its extreme thinness that the black scagliola was added at the end of the process. The layer of white scagliola, in which the design was carved, is visible between the black and the thick grey substrate.

There were several advantages to working this way round. It was easier and cleaner to draw the design and carve it onto a white surface than a black one. It was also possible to seal the white scagliola through a process of sanding and grouting before the design was cut away. This greatly reduced the problem of colour pollution from the black to the white scagliola. And while some fine-tuning was inevitable after the black coat had been applied and sanded back, most of the detail was carved in beforehand, saving time and again reducing the chance of colour pollution.

Black and white scagliola panel of St. Francis receiving the stigmata. The panel is one of three in a paliotto attributed to Annibale Griffoni, although the quality of the work suggests it may be by a later artist. Church of San Nicolo, Carpi.

Giovanni Gavignani (Carpi 1632-1680)

Giovanni Gavignani, who is said to have learnt from both Guido Fassi and Annibale Griffoni, produced altar fronts almost exclusively in black and white. His work reinforced the tripartite design of the paliotto and formalised it through the absence of colour. His pictorial skill, his dexterity as a carver, and the extraordinary amount of decorative detail that went into his designs, more than compensate for this; the subtle calibration of the cross-hatching – no easy thing to achieve in a material that chips so easily – gives considerable depth and expression to his figurative work.

His masterpiece is the altar to St. Anthony of Padua, in the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, signed and dated 1652, when he was just 20 years old. Of note are the magnificent flower vases in the two outer panels, strongly reminiscent of Wilhelm Fistulator’s vases in the Reiche Kapelle in Munich (c. 1630). Where some of Fistulator’s vases have a pair of butterflies hovering at the base of his vases, Gavignani included, alongside various flying insects, a spider dangling from a thread, presumably a symbol that held religious significance. Some commentators have seen the similarities between the designs as proof of collusion between Munich and Carpi, but a more probable explanation is that the two makers were working from similar prints that were circulating throughout Europe in the 17th century.

Altar dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua, in the church of San Niccolò in Carpi, by Giovanni Gavignano (signed and dated 1652).

Equally impressive in the St. Anthony altar front are the precision and detailing of the decorative ‘lace work’ around the edge, the frieze of scrolling acanthus across the top, and the four candelabra with antique vases, thick foliage and cornucopia. The central panel contains a picture of St. Anthony in adoration of the Christ child, taken from a print by Simone Cantorini.* The same subject appears in the painting above the altar. Unusually, there are two side altars, also faced with black and white scagliola. Each has a central panel with the depiction of an event from the Saint’s life, set in an inlaid oval frame surrounded with swirling foliage.

*Alfonso Garuti ibid. p 79

Details from the Altar of St. Anthony of Padua.

Gavignani is also credited with the scagliola altar surround, consisting of pedestals, columns and a pediment, similar in style to the work of Guido Fassi. For this he used a restrained colour palette of pale brownish pinks, greys and black.

A striking altar surround by Gavignani, both in terms of its colours and its modelling, is the altar of the Annunciation in the same church of San Niccolò. Black and gold scagliola for the columns and gradine (the ‘step’ above the altar table), provide a dramatic contrast with the brownish pinks used in the other areas. Paired consoles, one reversed on top of the other, form the outer edges of the reredos, an early example of baroque influence. The black and white scagliola altar front is also by Gavignani; the central image depicts the Annunciation, while the two side panels carry the coat of arms of the Barzelli family (one of whose members became a scagliolist – see below).

The Altar of the Annunciation, San Niccolò, Carpi. Paliotto and Surround by Giovanni Gavignano.

Gavignani was a prolific maker, and several of his works, signed and dated, can be seen in the Cathedral and the church of San Niccolò in Carpi. It is clear that he used the same designs on different altar fronts, sometimes interspersing them or varying them slightly, at other times repeating them exactly; fourteen years after making the St Anthony of Padua paliotto for San Niccolò, he made an exact copy for the Church of the Madonna of Lourdes in Reggiolo. He is also reported to have made memorial tablets, tabletops and small religious panels, the latter for domestic use as private objects of contemplation. He had a brother named Pietro Gavignani, who became ‘capo e maestro dell’arte della scagliola’ in 1644, and worked exclusively alongside him; no independent works of Pietro have been identified.

Giovanni Gavignani was the most accomplished of the first generation of Emilian scagliolists, a considerable artist and craftsman, whose mastery of the black and white inlaying technique was never surpassed. He died comparatively young, aged forty-eight.

References: Graziano Manni I Maestri della Scagliola in Emilia Romagna e Marche, Modena 1997.

Alfonso Garuti La Scagliola Carpigiana e l’Illusione Barocca, Modena 1990.

Anna Maria Massinelli, Scagliola l’arte della pietra di luna Rome 1997

Next/Chapter 19: The Carpi Masters – 2nd Generation